Abbeville Goes to War: The Story of the First Company Mirrors Cheers

Abbeville was cast in a significant role at the opening cue and at the closing of the curtain, in the greatest tragedy ever to hold our nation’s historical stage.

“If you are not ready to lay down life and fortune, you are not prepared for secession. The North cannot and will not part with you, and the treasure she wrings from you, without a mighty struggle.” – Armistead Burt. May 17, 1851, Abbeville Banner.

The gods of war decreed our nation’s gravest hour, then assembled at the chosen scene to consecrate the unleashing of the sword. The moment was at hand, around Charleston harbor a penetrating chill permeated the predawn darkness. Mist shrouded marshes lay unseen and silent. With the first, faint light of that tragic day filtering to the eastern horizon, torch and fuse touched. A Confederate mortar belched flame, sending its shell arching skyward to shatter the stillness as it exploded over the ramparts of Fort Sumter; vaguely discernable where the harbor opened to the sea. That tragic day was April 12, 1861. The fort was under the United States flag and garrisoned by Federal troops. It was a traumatic turn in a controversy almost as old as the nation itself. The right of a state to secede from the Union.

Several months earlier, the South Carolina Legislature convened to discuss the possibility of withdrawing the state from the Union. The Abbeville District held what is purported to be the initial meeting, adopting resolutions advocating for the state's secession. Following the secession, the District organized a First Company for the state's inaugural regiment and subsequently endured significant hardship during the ensuing conflict. These narratives chronicle the events and emotions experienced by the individuals involved, capturing their philosophical outlook and dedication to duty as perceived in a period marked by severe suffering, turmoil, and devastation that affected the area, state, and nation profoundly.

Ever consistent with the laws of his nature, conflicting philosophies stir the passions of men, inciting polarization, begetting confrontation and bloodshed. So is determined the course of history and the destiny of nations.

The question of sovereignty of State vs. Union arose as a painful issue to haunt the unity of our youthful nation. By early 1861, the unhealing wounds had festered into armed confrontation. The port city of Charleston stood as the focal point of our troubled nation. The tragic hour of decision arrived. It was April 11, 1861. Chieftains of contending forces conferred under flags of truce, observing the courtesy appropriate to their calling, but grim and determined in their respective positions and obligations. The sun set on a tense city that evening of April 11, 1861. As the hours of darkness passed, reports and rumors as to the continuing negotiations intensified the excitement. The streets were filled with throngs of people, and crowds gathered in outlying areas. The moments ticked away. The steeple clock tolled the hour of midnight. The calendar marked the date—April 12. The vigil was kept. Finally, word of an eagerly awaited decision was passed. The die was cast—Confederate forces would open fire on Fort Sumter.

The people left the streets to gather again, crowding every advantage point about the city and harbor to peer intently seaward into the darkness. Only vaguely could they discern the harbor’s outreaches, and the mass of a structure out there where its waters met the sea. Each moment was lived. Suddenly, out of somewhere, a burst of light burned a hole in the darkness. A cannon thundered. It was the cue. Boundless cheering was spontaneous. It was the parting of the curtains. None could know that it was the opening scene of a tragedy destined to remain unparalleled in our nation’s history. It was the dawn of an era of bloodshed, grief, suffering, and destruction inconceivable by those who viewed and cheered the spectacle.

Present and swept up in the spirit of the day was a company of Abbevillians. Who were they? What sequence of events had destined them as participants in this momentous moment of our nation’s history?

In the fall of 1860, as the nation’s crisis had deepened, the South Carolina Legislature was called into special session. Resulting from this session was a resolution calling for a convention to be held on December 17th, for the consideration of taking the state out of the union. The convention was to consist of delegates representing each district in the state.

Events moved rapidly. Pursuant to the action of the Legislature, a meeting was held in Abbeville on November 22nd. The Abbeville Press, dated Friday, November 23, 1860, reported:

“One of the largest and most enthusiastic meetings ever held in our District convened in our village on yesterday. Companies of Minute Men were present from Cokesbury, Greenwood, Ninety-Six, Bradley, Due West, Donaldsville, Wickliff’s and Calhoun’s Mill. The Old Artillery Company, The Southern Rights Dragoons, and an immense concourse from every section of our District were present. Banners were flying in all directions and the booming of cannon added to the general excitement.”

By early morning on the 22nd, a huge crowd had gathered at the courthouse. As the planned activities got under way, a procession was formed under the direction of General Augustus M. Smith, Marshall of the Day. Colonels W. M. Rogers and J. F. Livingston, Jr. served as Assistant Marshals. Leaving the courthouse, the procession, with bands playing and escorted the Minute Men approximately 500 hundred strong, moved to the grove near the depot (today, Secession Hill) where a stand had been erected. The setting overlooked the town’s depot where state dignitaries had arrived for the occasion. The presiding officer was Thomas C. Perrin, Esquire. Vice Presidents were Judge D. L. Wardlaw, Colonel John A. Calhoun, Dr. J. W. Hearst, John Brownlee and Dr. John Logan, Sr.

The meeting opened with prayer by Reverand North. President Perrin, in a brief speech, then reviewed the causes which had led to the present crisis in our history. He stated the purpose of the meeting as being twofold: for consultation as to what course the District should pursue in the crisis and nomination of delegates to represent the District in the Convention set for December 17th.

A series of ardent speakers followed. The Honorable A. G. McGrath of Charleston delivered what is described as being a most eloquent and soul-stirring speech on behalf of States Rights and Southern Independence. He forcefully stressed the necessity for prompt action.

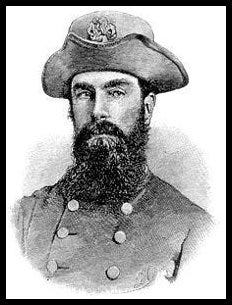

The speech by General Milledge L. Bonham is described as having been the most eloquent in style and was loudly cheered by the crowd. His message was that the time for compromise was past; the time for action had come. Then, Judge D. L. Wardlaw rose to speak. A moderate voice, he called attention to the North’s industrial might with the vast capability for producing armament and shipping. He cautioned that secession would end in War. “What can we do,” he asked, “if the North sends warships to bombard our coastal cities?” “We’ll wade out and sink ‘em damn ‘em” came a voice out of the crowd, tumultuously cheered by the throng.

During the meeting, a series of resolutions were introduced by Edward Noble, Esq. and Thomas Thompson. Those resolutions called for the secession of the state from the Federal Union and were promptly and unanimously adopted. The Chair appointed a committee of twenty-one to nominate suitable persons to represent the District at the convention. The delegates appointed were the following: Edward Noble, John A. Calhoun, John H. Wilson, Thomas C. Perrin, Thomas Thompson and D. L. Wardlaw.

The Independent Press described the atmosphere in the town following the meeting:

“At night there was a grand display of fireworks, and our public square blazed with bonfires and illuminations. An imposing torch light procession was formed and after making a brilliant demonstration in our streets, halted in front of the Marshall House (the town’s elegant hotel fronting on the square at the corner of Washington and Main streets), where an enthusiastic crowd was addressed by a succession of speakers, whilst ever and anon, the strains of spirit stirring and the shouts of the multitude made the welking ring.”

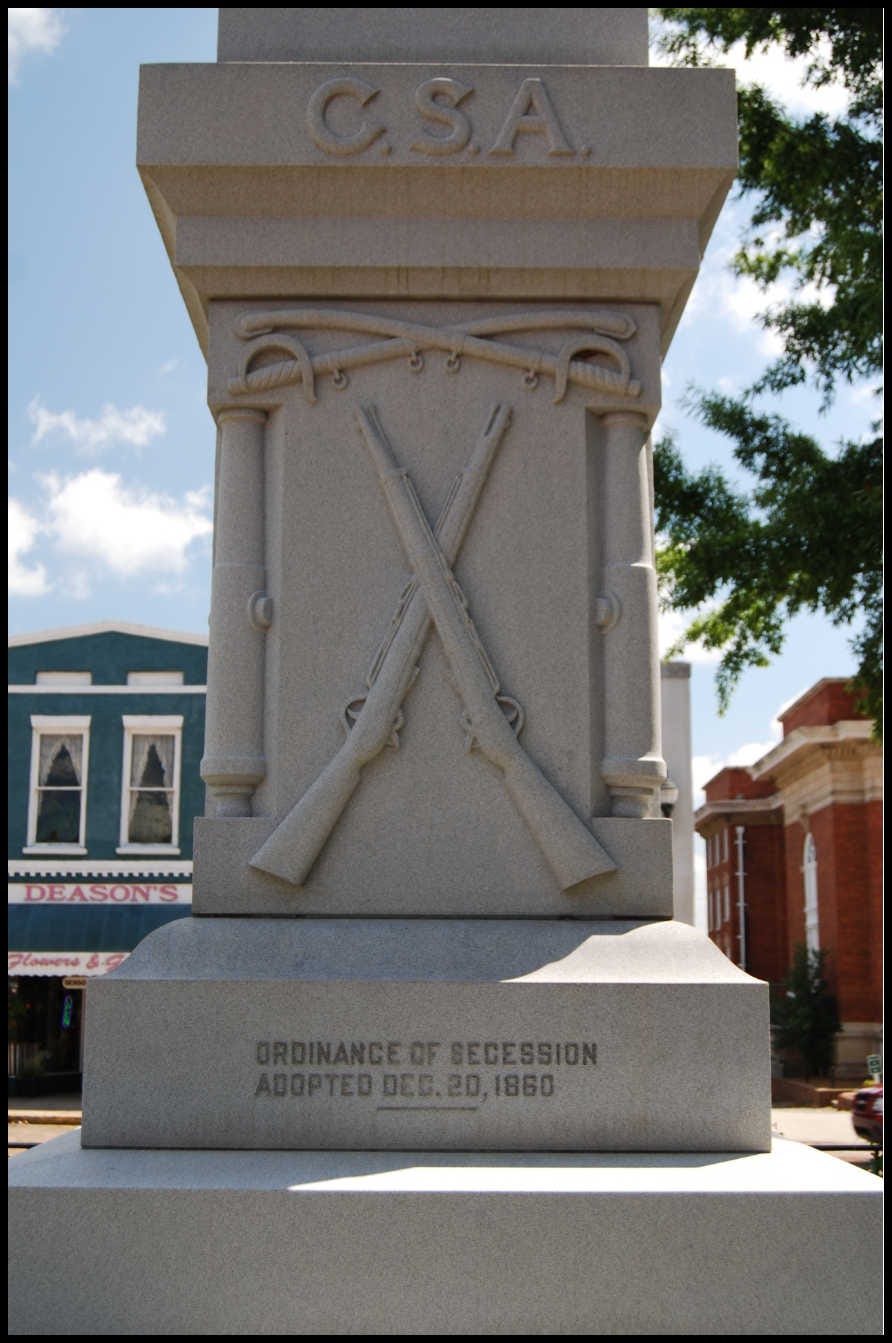

The convention which had been called for by the state legislature found itself in St. Andrews Hall, Charleston, on December 20. The committee which had been appointed to draft an Ordinance of Secession made its report. The draft nullified the act of South Carolina of May 23, 1788, by which the state had ratified the Constitution. It stated, in part, “The union now subsisting between South Carolina and other states under the name of the United States of America, is hereby dissolved.” The Ordinance was promptly acted upon and adopted by a unanimous vote of the 169 delegates present.

Word of this action electrified an already excited populace. The Charleston Mercury described “church bells ringing out joyful peals, artillery salutes thundering from the Citadel, new flags everywhere thrown to the breeze, and volunteers in their uniforms hurrying to and fro about the streets.”

That evening the Convention was reconvened in Institute Hall amid cheering crowds of citizens. The Ordinance was presented and signed by every member of the convention. The President of the proceedings, his voice dominating the hall, then announced that “The Ordinance of Secession has been signed and ratified and I proclaim the State of South Carolina an Independent Commonwealth.” The act was done. The Secession movement had been without opposition. There were those who saw it as folly and had stood steadfastly against it. But now they had been inundated by the tidal wave of secessionism. The noted B. F. Perry of Greenville voiced himself to those who had swept the field. “I have been trying to prevent this sad issue for thirty years,” he said. “Now you are all going to the devil and I will go with you. Honor and patriotism require me to stand by my state, right or wrong.” Perry had spoken the sentiments of the opposition. The State stood united.

The convention realized that one of the first needs of the new Republic would be an army to protect its sovereignty. Colonel Maxey Gregg, then a prominent lawyer from Columbia, was commissioned to raise a regiment for the state.

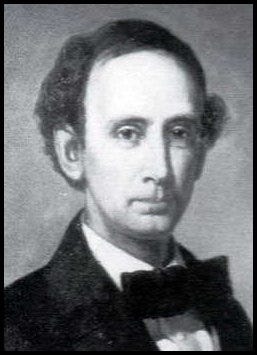

Colonel Gregg, in turn, commissioned Captain James M. Perrin of Abbeville Court House (now Abbeville) to raise a company for the regiment. Captain Perrin was then a prominent lawyer representing Abbeville District in the state legislature.

As Captain Perrin went about his duties of raising his company, two of its first members were sons of the wealthy and prominent Haskell family whose large plantation lay approximately eleven miles west of the town. When the company’s quota had been filled, it stood 100 strong. Described as being composed of the area’s best citizens, it included ten honor graduates of South Carolina College (now the University), “As fine a looking body as any that could be raised.”

On the eve of their departure, attires in their uniforms of “red frocks and dark pants,” the company was drawn up in front of the home of R. A. Fair, Esq. The occasion was for the presentation of a flag which had been fashioned for the company by the ladies of the area.

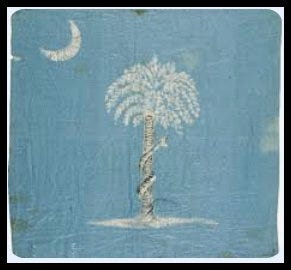

The flag is described as having been made of blue silk with a gold fringe. On one side in the center of the blue field was a lone star with the words, “The fair to the brave.” On the other side was a palmetto tree with a rattlesnake coiled about its trunk and the words in Latin, “Don’t tread on me,” and also the dates, 1776 and 1860.

The flag was presented, from horseback, to the Company Commander by one Miss Sallie Martin. Her presentation speech is as follows:

“Captain Perrin, on behalf of the ladies of this District, permit me to present to the company of Minute Men, which you have the honor to command, this flag. Receive it as a testimonial of the devotion of woman’s heart to the cause to which you are so nobly espousing, as evidence of the fact that in your triumph, we will rejoice, or, in your fall weep in anguish o’er your bloody graves.

We feel that our flag is committed to strong arms and brave hearts, that its folds will never be allowed to ingloriously fan the dust. Soon may it proudly float with the boarders of a brilliant Southern Confederacy.”

Captain Perrin graciously accepted the flag and responded as follows:

“Fair lady, in the days of chivalry, the brave knight was encouraged to deeds of daring by the smile of his lady love. For her honor he entered the list and contended against foes visible and invisible; for her safety, he imperiled his life upon the battlefield. In time of peace, in noble strains he sang of her beauty and virtue. The days of chivalry have passed, and the voice of the troubadour is hushed in silence, but it is still true, lady, that the highest aim of a soldier is by deed of valor to win the approving smile of the fair.

With hearts of gratitude and pride, we receive from your fair hands this beautiful banner. It bears upon its azure field the emblems we all love. The Palmetto reminds us of our allegiance to our commonwealth. The lone star reminds us of her heroic position, standing in vindication of her rights with the strong arm of the government which she has left threatening to crush her.

The dates which I see upon the coat of arms recalls the most lively emotions. The date, 1776, is as dear to us as it ever was. It recalls our glorious deliverance from British bondage. The date, 1860, recalls a more glorious deliverance from the tyranny of a fanatical majority. The first date recalls the deed of our sires, the last proves we have not forgotten the lessons which they have taught us.

How soon this beautiful banner is to be unfurled upon the field of battle and blood, none can tell. When the time comes, lady, we hope to win the title which you have given us. The Brave. Be assured, this flag shall be borne by hands and sustained by hearts that will never forfeit your good opinion. When our country is to be defended and honor with, then shall it wave, and never shall it trail in the dust until the arms of my command are nerveless and it becomes the winding sheet of the last survivor.

Lady, on behalf of my command, I tender to your fair self and the ladies of Abbeville, whom you represent, my grateful thanks for this manifestation of sympathy and kindness.”

Captain Perrin then passed the flag to 5th Sergeant John W. Lesley and charged him as follows:

“Sergeant Lesley, this flag has been received from the hands of the fairest of the fair. In entrusting it to your keeping, I feel that it is safe and that you will faithfully redeem the pledges which I have made on behalf of this command. You are expected to guard its honor as your own to bear it in the center of your company in the thickest of the fight and whether on the battlefield or off of it, you will ever remember that it is the gift of the fair to the brave.”

Sergeant Lesley responded to the charge:

“Ladies, when the tug of war shall come and Greek meets Greek, then the beautiful banner that you this day so kindly presented to us will be thrown to the breeze. We’ll look to it and remember that the ladies of Abbeville will expect us to defend it and them, and we’ll do it.”

The occasion was attended, with much interest, by the families, friends and well-wishers of the men who were going away with the company. “It was a truly interesting occasion to be long remembered by all who witnessed it,” said the Independent Press.

The following morning the company departed from Abbeville for Charleston. “They left with buoyant hearts, conscious of the noble cause for which they had volunteered,” noted a writer. The morning of their departure was January 9, 1861. It was the same morning on which the Citadel Cadets opened fire on the Federal ship Star of the West.

Upon the company’s arrival in Charleston, it went into quarters on Sullivan’s Island and began intensive training. Days after its arrival, an accident occurred which resulted in the first death of a member of the company. J. Clark Allen ran onto a bayonet in the hands of a fellow soldier. The bayonet pierced through the eye socket and death was instantaneous. Allen is said to have been the first soldier to die in the service of the Confederacy. His remains rest today in the Long Cane Cemetery.

On those fateful days of April 12 and 13th, members of the company watched the bombardment of Fort Sumter. Before the close of the day of the 13th, the Fort surrendered. Victory was in the air, and spirits were high. The Independent Commonwealth of South Carolina had struck and prevailed. Its port city had been freed of foreign troops.

Soon the company returned home to Abbeville and to a hero’s welcome. A “grandiose banquet” was prepared for them at the Marshall House, Abbeville’s eloquent Antebellum hotel standing at the corner of Washington and Broad streets (Broad St. is now today North Main). The dining hall was described as being beautifully decorated with wreaths of evergreen and with festoons of flowers suspended on all sides, “Whilst at the extremity of the room the words ‘welcome home’ in large letters indicated the character of the feast. The long and spacious tabled fairly groaned under the weight of meats and vegetables of every variety and in profusion formed a rich feast,” as described by the Independent Press.

The banquet began with the roll of drums as the company, under the command of Captain Perrin, formed ranks and marched to the front of the “dining saloon.” The Honorable Armistead Burt acted as President and Thomas Thompson Esq. as Vice President for the occasion. The speeches were numerous and eloquent.

When Captain Perrin rose to respond to the speeches of honor, he explained why his company had not gone from Charleston to Virginia. He continued that his men, however, would be ready to meet the roll call of danger wherever their country’s (the Confederacy’s) flag unfurled. Not all members of the company had returned to Abbeville. Some had gone from Charleston to Virginia with Gregg’s Regiment—just in case the Yankees should be so rash as to again test southern mettle. Here at the feast the atmosphere of gaiety reigned. That the North would fight to prevent the Southern states from leaving the Union was an unrealistic conclusion.

The war did become a reality and true to Captain Perrin’s pledge, every member of his first company of Abbeville volunteers had soon joined various units on the far-flung battlefield of the southern perimeter. Their lot was four years in the fearsome and pathetic tragedies of war, while they saw the Southland bled to exhaustion, deprivation, and best by defeat. Then came the Appomattox. The war had ended. The surviving members of that first company, along with their comrades, laid down their arms and began the long trek homeward. Caldwell described them:

“Great and various was their wretchedness. They were sun-burnt, gaunt, ragged, scarcely at all shod, spectres and caricatures of their former selves. Clothing and shoes consisted of little other than what could be picked up on the battlefield. Fed on half cooked dough, often raw bacon and raw beef—had devoured green apples and corn—had contracted diarrhea and dysentery of the most malignant type. They were covered with vermin. They stood an amarcid, limping, ragged, filthy mass whom no stranger to their valiant exploits could have believed capable of anything the least worthy.”

As the members of that first company straggled back to Abbeville, there were those who again did not return. There had been only the pathetic message: killed at Nashville, killed at Gaines Mill, killed at Gettysburg, killed at Second Manassas, died of disease, etc. Of the first two members to join the company, the Haskell brothers, William C., was killed at Gettysburg; Alexander, was twice severely wounded, including one eye being shot out, but survived the war.

As for Captain Perrin, his response to the presentation of the flag had been no idle boast. He fell mortally wounded at the lead of his troops while leading them forward in a phase of the bitter fighting at Chancellorsville. Captain Perrin had achieved the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and was commanding the First Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers at the time he fell. 5th Sgt. John W. Lesley lost an arm in the war and later died on his farm near Abbeville.

Abbeville was cast in a significant role at the opening cue and at the closing of the curtain, in the greatest tragedy ever to hold our nation’s historical stage. Abbeville District with an 1860 white population of 11,516 had 349 men killed in action. This did not include the wounded or those who died of disease. By comparison, Abbeville County with a population of 22,932 had 72 men killed in action during all of World War II.

1st South Carolina Infantry Regiment, Greggs (McCreary's), C.S.A.

This flag is an example of a combined state flag/regimental flag. On one side (pictured) is the regimental designation "1st Regt. S.C. Volunteers" surrounded by a floral wreath display. On the reverse side the South Carolina Palmetto was surrounded by a laurel wreath and featured the crescent moon in the upper hoist corner. This flag was carried along with an ANV type by the regiment from the Seven Days Battles through Gettysburg, after which it was returned to South Carolina for display and safekeeping. It now resides at the South Carolina Relic Room in Columbia, South Carolina.

1st South Carolina Infantry Regiment is also known as the 1st Provisional Army, Gregg's Regiment and McGowan's Regiment. "Col. Gregg was technically over a brigade, and after his death, command of the brigade went to Gen. McGowan. Command of this regiment was for a time under Col. Cornillus McCreary, hence the names". (From SC 1st Infantry Regiment (Gregg's)

1st Infantry Regiment, Provisional Army completed its organization at Richmond, Virginia, in August 1861. Most of the officers and men had served in the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, a six-month command, which was mustered out of service in late July. The men were from Charleston and Columbia, and the counties of Darlington, Marrion, Horry, Edgefield (now Aiken), and Florence. On April 9, 1865, it surrendered.

"Gregg's (McCreary's) First South Carolina Regiment: Companies and Counties of origin

Company A - (also known as Gregg's Guards) - Many men from Barnwell District (County)

Company B - (also known as Rhett's Guards) - Many men from Newberry Newberry District (County)

Company C - (also known as Richland Guard or Richland Rifles) - Many men from Richland District (County), Columbia area.

Company D - (also known as Pee Dee Rifles), (also known as Abbeville Volunteers) - Many men from Darlington District (County)

Company E - (also known as Marion Volunteers (Rifles)) - Many men from Marion District (County)

Company F - (also known as Horry Rebels) - Many men from Horry District (County)

Company G - (also known as Butler Sentinels) - Many men from Edgefield District (County)

Company H - (also known as Haskell's Rifle Corps) - many men from Edgefield District (County), Beaufort District (County), Charleston District (County) and Abbeville District (County)

Company I - (also known as Richardson Guards and Carolina Light Infantry) - Many men from Charleston District (County)

Company K - (also known as Irish Volunteers) - Many men from Charleston District (County)

Company L - (also known as Carolina Light Infantry) - Many men from Charleston District (County)

Company M - (also known as the Furman Guards and William H. Campbell's Company) - Many men from Greenville District (County)

1st Infantry Regiment, Provisional Army completed its organization at Richmond, Virginia, in August 1861. Most of the officers and men had served in the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, a six-month command, which was mustered out of service in late July. The men were from Charleston and Columbia, and the counties of Darlington, Marrion, Horry, Aiken, and Florence. Assigned to General Gregg's and McGowan's Brigade, the unit fought with the Army of Northern Virginia from the Seven Days' Battles to Cold Harbor. It was then involved in the difficult Petersburg siege north and south of the James River and the Appomattox Campaign.

This regiment lost 20 killed and 133 wounded during the Seven Days' Battles, had fifty-three percent disabled of the 283 engaged at Second Manassas and Ox Hill, and had 4 killed and 30 wounded at Sharpsburg. It sustained 73 casualties at Fredericksburg and 104 at Chancellorsville, then lost thirty-four percent of the 328 at Gettysburg. There were 16 killed, 114 wounded, and 7 missing at The Wilderness, and 19 killed, 51 wounded, and 9 missing at Spotsylvania. On April 9, 1865, it surrendered with 18 officers and 101 men.

The field officers were Colonels Maxey Gregg, Daniel H. Hamilton, and Charles W. McCreary; Lieutenant Colonels T. Pinckney Alston, Andrew P. Butler, Edward McCrady, Jr., Washington P. Shooter, and Augustus M. Smith; and Major Edward D. Brailsford.

Battles and Engagements

Seven Days Battles

Battle of Gaine's Mill

Battle of Frayser's Farm

Battle Of Second Manassas

Battle of Ox Hill

Battle of South Mountain

Battle of Sharpsburg

Battle of Shepherdstown

Battle of Fredericksburg

Battle of Chancellorsville

Battle of Gettysburg

Battle of Falling Waters

Bristoe Campaign

Mine Run Campaign

Battle of the Wilderness

Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse

Battle of the Bloody Angle (Muleshoe Salient)

Battle of North Ana

Battle of Jericho Ford

Battle of Cold Harbor

Siege of Petersburg

Battle of Squirrel Level Road

Battle of Pegram's Farm

Battle of White Oak Road

Battle of Five Forks

Appomattox Courthouse

Deo Vindice!

Hi Monica,

It’s been awhile. I have marveled for decades maybe all of my adult life about Courage. As a Warrior I was tested on the field of Battle and wasn’t ever afraid. Perhaps trepidation over unknown but never in a Fire Fight.

But that’s singular. It only represents the thought processes of the individual.

The Courage of the South was a different dynamic. They felt multiple grievances that could not be mitigated and the frustration and threat to their way of life was being tested to the extreme.

The choice of succession was to most extreme but in the minds of leadership the only venue left. This had to mean a future war against a much superior force but out of pride and to many the only honorable choice left.

This is where Insanity and Courage has conflicted in my mind and no doubt others.

We watch now the overwhelming conflict going on here and globally between the globalist ideology and God Loving and Fearing Peoples. We have watched for six decades False Flag Wars, Millions of innocent lives lost, the Hoax Covid19 Plandemic, the Death Jab, Weather Manipulation, and DEW Direct Energy Weaponry.

The EU, Great Britain and others have lost their way by the voting majority if the elections are honest. The same can be said for New Zealand, Australia and Canada.

The People’s Voices spoke here in November 2024. We The Real People mandated Change. Candidate and now President promised change. Elon Musk through DOGE delivered an overwhelming audit of the corruption within our Government.

President Trump has tried to deliver on His promises to rid us of Illegal Immigration. He has began the tariff War that will prove to bring jobs back and finally level the playing field on imports and exports.

He had via executive order rid Women Sports the horror of competing with biological men. His other executive orders are all for Putting America First.

But the neocons, leftist, democrats, WEF, WHO, Central Bank, the inherited CIA, FBI, DOJ, Pentagon and Military Industrial Complex, Mass Media and now lower Federal Courts block We The Real People’s Mandate and His Programs.

So now I ponder if and when we will be forced to make the choice of Insanity and Courage. How far will the outcry publicly go on the deaf ears of the Deep State Controlled Government’s across the globe.

We as a people do not want another Civil War. But nor do we want our Children and Their Children’s birthrights sold out to the Deep State.

Insanity, Courage, Patriotism and Self Preservation and America First may become just a Heartbeat Away.

I Pray You and Yours Are Doing Well.

😇🙏🏾❤️🇺🇸

Semper Fidelis

Reposting on other social media

Thank you