Beneath the Southern Cross Part 1

A three-part article about the origins of the Confederate Battle Flag

The Confederate Battle Flag, sometimes called the Southern Cross, is held in disfavor by many who are unfamiliar with its origin and true symbolism. Many have been taught to treat it as an object of moral horror and political infamy. A deadly combination of ignorance and arrogant self-righteousness is constantly engaged in shouting down its true meaning and history. Demagogues freely defame it, while moral cowardice acquiesces to outrageous distortions of the truth. The apathetic allows its true history to be buried under decades of slanderous propaganda. It is incumbent upon those who value truth, fairness, goodwill, reasonable tolerance, and charity in society to educate themselves on the true history and meaning of its famed banner.

In order to understand fully appreciate the meaning and heritage of the Confederate Battle Flag it is necessary to reach back far into history and then come forward to the battlefields of its fame. Finally, we must visit the hallowed resting places of the fallen and of the veterans of that historic struggle.

The prominent design feature of the Battle Flag is its diagonal cross or saltier. This has many centuries been a preeminent Christian symbol. In the Greek alphabet the name of Christ begins with the letter “X” or “Chi.” Thus it became a symbol for Christ and Christianity.

The symbol was reinforced when the Apostle Andrew was martyred on a diagonal cross in 60 AD. This was later to influence the Christian symbolism of far-off Scotland. About 357 AD, during the reign of Constatine, some of the bones and relics of Andrew were brought to Constantinople. According to many legends some of these were eventually moved to a monastery near a small Pictish village on the East Coast of Scotland, probably about 733 AD. The town that grew up there was renamed St. Andrews and became the ecclesiastical capital of Scotland and a center for learning. Hence there began to be an identification of Scotland with St. Andrew and the diagonal cross on which her was martyred.

In a battle around 832 AD, Angus MacFergus, King of the Picts, with a combined army of Picts and Dalriada Scots, drove the Northumbrian Angels out of Scotland. Various legends attend this battle, including the appearance of the white diagonal cross in the blue sky that day. Whatever is behind the legends, the bottom line is that Angus, the Picts, and the Scots attributed their victory and rout of the Angels to the intercessory assistance of St. Andrew. All this is clouded in the fog of history and legend. St. Andrew was eventually recognized as the Patron Saint of Scotland. Since early in the 12th century the Scottish national flag, also called the St. Andrews Cross, has been a white diagonal cross or saltier on a field of blue.

The important thing about the St. Andrews flag to the Scots was that is was an identification of themselves as Christian people. Many Europeans nations chose the cross in various designs to identify themselves as Christian nations.

The English flag is a red perpendicular cross, called St. George’s Cross, on a field of white. The British national flag contains the English St. George’s Cross with a diagonal St. Andrews Cross of Scotland, and the red diagonal St. Patrick’s Cross representing Northern Ireland. All the Scandinavian countries including Finland, Greece and Switzerland use a cross in their flags.

The Southern Cross or Confederate Battle Flag with its white trimmed blue diagonal on a red field is a descendent of the Scottish St. Andrews Cross. As I will show, it was meant to be a preeminently Christian self-identification of the Southern people.

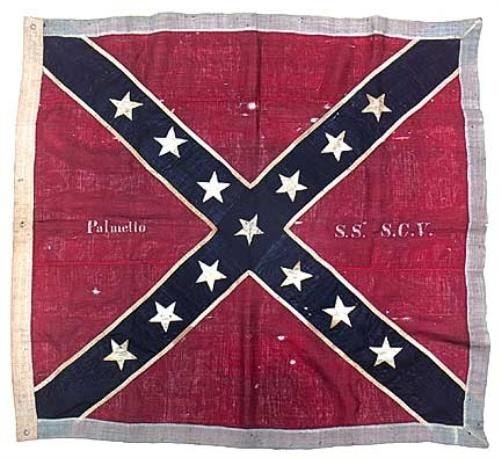

On December 20, 1860, the elected delegates of the South Carolina Secession Convention met in St. Andrews Hall in Charleston. One of the 169 delegates was U.S. Congressman and future Confederate Congressman, William Porcher Miles. Miles had a very keen interest and knowledge of heraldry. Besides their famous Palmetto Flag, South Carolinians had prepared a special South Carolina Sovereignty Flag for the occasion. This flag, which probably had the touch of William Miles, was a blue St. Georges Cross on a field of red, with a white South Carolina Palmetto and Cresent in the upper left canton. The 15 white stars on the cross represented the hope of a 15 state Confederacy. Again, the important thing about this flag was that its symbolism identified with Christianity.

One of the underlying causes of the war was the growing religious difference between the North and the South. By 1850 the original Calvinism of the New England Puritans had been in steep decline for generations. The Calvinism and orthodox Christianity of the Puritan fathers was being eroded and displaced by Deism, Unitarianism, Universalism, and Transcendentalism, the antecedents of modern liberalism. A few strong bastions like Princeton remained, the authority of Scripture, the sovereignty of God, and the centrality of Christ’s redeeming grace were fighting a rear-guard battle against secularism and numerous heresies. In addition, the man-centered preaching of Charles G. Finney further weakened the theology of Northern Christianity. The godly zeal of the first Puritans had been replaced by zeal to reform society by government force.

The South on the other hand was not only holding fast to traditional Christian teachings, but was experiencing dramatic revival, culminating in more than 150,000 conversions of the Confederate Army alone during the war. These growing religious differences caused considerable anxiety and mistrust of Northern goodwill in the South, especially after John Brown’s 1859 raid on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, now in West Virginia. John Brown, a fanatical abolitionist and cold-blooded murderer of innocent Kansas farmers in 1856, was hanged by federal authorities, but he was made a hero and martyr in the North by the press, and most alarmingly, many influential abolitionists preachers. Many famous Northern personalities compared John Brown’s hanging to the martyrdom of Christ. Here for example are the words of Julia Ward Howe, who composed the words for The Battle Hymn of the Republic: “John Brown will glorify the gallows like Jesus glorified the cross.” A few other admirers of this terrorist who became important in the liberal propaganda version of American history and culture were Reverand Henry Ward Beecher, Henery David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Many statements glorifying such lawless violence in the name of abolition alarmed the South and intensified their desire to disassociate themselves with the North. It also further intensified in Southerners their desire to identify themselves as a distinctively Christian people.

Because of his knowledge of heraldry, Miles, now a Confederate Congressman from South Carolina, was appointed Chairman of the congressional committee to select a national flag for the newly formed Confederate States of America. On the deadline date of March 4, 1861, the work of the committee was presented to the Confederate Congress. Out of numerous suggestions the committee had narrowed the field down to four choices.

One of these choices was William Miles’ own. It was essentially the South Carolina Sovereignty Flag except that the cross was changed from a St. Georges Cross to a diagonal St. Andrews Cross, and of course, without the Palmetto canton. There were only seven stars on it, however, because on March 4th only seven states had properly seceded and joined the Confederacy. This made it asymmetrical and was one of the reasons it was rejected as the new National Flag. The flag chosen was the “Stars and Bars” which had a circle of seven white stars on an upper left, blur canton and three horizontal bars red, white, and red.

One of the main reasons this flag was chosen over Miles’ St. Andrews Cross was that “Stars and Bars” was close resemblance to the United States Flag. At that time the Confederate Congress wanted to keep its identification with the 1787 United States Constitution. They believed they had been faithful to it, but the Northern states, especially the Northeastern industrial states had continually tried to undermine it for Northern profit at Southern expense.

This is itself a clue or two other important causes of the war. The Southern belief was in government of Law and strict constitutionalism versus majoritarian rule and manipulation of the Constitution. In addition, the North had imposed enormous tariffs on manufactured goods that protected Northern industry at considerable expense to Southern agriculture, trade, and the Southern economy. The Confederate Congress passed over Miles’ St. Andrews Cross for the Stars and Bars, but Miles did not give up promoting his choice for some honorable Southern use.

In the early battles of the Civil War, it was noted that there was often confusion on the battlefield because of the similarity of the Stars and Bars to the US Flag. After the first battle of Manassas at Bull Run Creek both Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and his commander, Joseph E. Johnston were convinced that there was a need to change the flag. Battlefield commanders needed to identify their troops and positions on the field without confusion, despite the smoke and dust.

To be continued…

Part 2. How the Southern Cross was officially accepted.

South Carolina Sovereignty flag is flying outside my gate, right now.

It flies below the flag of South Carolina.

I’m writing a novel about my ancestors and incorporating the facts about the confederacy and their true intentions. Your essay is enlightening and informative. Thank you.