Camp Douglas Eighty Acres of Hell

One of most extreme POW camps during the War for Independence.

According to Union Army records, 4,454 Confederate prisoners of war died at Camp Douglas, located on the south side of Chicago. These records are incomplete, however, and the actual number is estimated to be more than 5,600 soldiers. According to The Sons of Confederate Veterans, there are about 6,000 graves in the cemetery there. Of the 30,218 Confederate soldiers who died in POW camps, Camp Douglas was the first in the list of infamy. Other names topping this dismal list were Point Lookout, Maryland (3,584); Elmira, New York (2,933); Fort Delaware, Delaware (2,466); Rock Island, Illinois (1,960); Camp Morton, Indiana (1,763); and Gratiot Street in St. Louis, Missouri (1,140).

Historian Thomas Cartwright has described Camp Douglas as “a testimony to cruelty and barbarism.” Because of its miserable living conditions and increasingly degrees of deliberate cruelty towards Confederate prisoners of war, the camp gained the title, “Eighty Acres of Hell.” Prisoners were intentionally deprived of adequate rations, clothing, and heating as punitive measures. From September 1863 to the end of the war, many were subjected to brutal tortures that often resulted in permanent maiming and death.

Camp Douglas was originally a fairground. As the start of the war, it was used as a center for training and quartering Union regiments raised in the Chicago area. It was named for Illinois statesman presidential candidate, and U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas. The camp consisted of 64 barracks, a small hospital, and other prison buildings. The top capacity of the prison was about 6,000, but eventually over 12,000 would be crowded into its confines.

On February 21, 1862, the first group of Confederate prisoners arrived in Chicago by train. As they were marched to their quarters at Camp Douglas, crowds of onlookers, enraged by Union war propaganda, cursed them, and some even hurled rocks at the men. But the captures Southerners would soon face far more deadly ravages of nature and disease.

Unfortunately, Camp Douglas was situated on low ground, and it was flooded with every rain. During the winter months, whenever temperatures were above freezing for long, the compound became a sea of mud. Less than a handful of the barracks had stoves. Overcrowding and inadequate sanitation measures soon made the camp a stinking morass of human and animal sewage. Henery Morton Stanley, of the 6th Arkansas, who later in his illustrious career as an African explorer and journalist uttered the famous words, “Dr. Livingston, I presume,” had this to say about Camp Douglas:

“Our prison pen was like a cattle-yard. We were soon in a fair of rotting while yet alive.” He later remarked that some of his comrades, “Looked worse than exhumed corpses.”

Steadily, sickness and disease began to increase. By early 1863 the mortality rate at Camp Douglas had climbed to over 10 percent per month, more than would be reached in any other of the prisons, Union or Confederate. The U.S. Sanitary Commission, now the Red Cross, pointed out that at that rate, the prison would be empties within 320 days. One official called it “an extermination camp.” The fall and winter of 1862-1863 were very wet, cold, and windy. The majority of deaths at the camp were from typhoid fever and pneumonia as a result of filth, bad weather, poor diet, lack of heat, and inadequate clothing. Other diseases included measles, mumps, catarrh (extreme upper respiratory sinus and throat infection), yellow fever, chronic diarrhea, and hospital gangrene.

Somewhere in excess of more than 317 Confederate soldiers escaped from Camp Douglas, over 100 of them being Morgan’s 2nd Kentucky Calvary. Hundreds of Morgan’s men had been sent to Camp Douglas after being captured on their famous raid through Indiana and Ohio in July 1863. However, during the daring escape of these Morgan cavalrymen resulted in retaliatory action. A reduction of rations and the removal of a few of the barracks’ stoves were ordered down from Washington. Eventually all vegetables were cut off. This resulted in an epidemic of scurvy described by R.T. Bean of the 8th Kentucky Calvary. “Lips were eaten away, jaws became diseased, and teeth fell out.” Before authorities could correct the situation, many succumbed to the disease. In addition, an epidemic of smallpox raged through the camp. Lice were everywhere. Many prisoners had to supplement their diet by catching, cooking and eating the all too abundant rats.

The first commander of Camp Douglas as a POW camp was Colonel James Mulligan of the 23rd (Irish) Illinois Infantry. The prisoners respected Mulligan, even though he was the enemy, because of his heroic war record and honesty. He was a strict disciplinarian but always fair. With more prisoners pouring into Camp Douglas than could be handled with efficiency and mounting sanitary conditions, he was glad to take his regiment back to the field in June 1862. Though he felt his record had been sullies by the problems at Camp Douglas, his valor and leadership in battle soon won him promotion to Brigadier General. Sadly, he was killed in action at Winchester, Virginia, in July 1864. His last words were, “Lay me down and save the flag,” while being carried from the field. His monument dominates the western entrance to Calvary Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois.

Being commandant of a prisoner camp was not considered a desirable position by most Union officers. During its four years history the camp had eight commanders. Most of these were honorable men, who later proved their worth in battle and in peace. The punitive policies had come directly from the War Department. Early in President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton termed all captured Confederates as “traitors” and refused to recognize them as prisoners of war. Nevertheless, public pressure resulted in a prisoner exchange program in July 1862. Camp Douglas was emptied twice by prisoner exchanges, in August 1862 and in May 1863, just before Lincoln and Stanton seized the opportunity to discontinue them. Prisoner exchanges were more value to the badly outnumbered Confederates, and Lincoln and Stanton hoped by eliminating them to exhaust Southern manpower. This decision later resulted in much suffering for both Confederate and Union prisoners (most notably at Andersonville).

Nearly 8,000 Union soldiers on parole and awaiting official exchange were held at Camp Douglas rather than sent home on leave in late 1862. These frustrated soldiers, who quartered themselves just outside the camp mutinied and burned down a third of the camp before order was restored by regular Union Army troops.

The commanders of Camp Douglas also had to put up with rampant military and political corruption. There was a scandal over the prices and quality of food rations. Orville Browning, a personal friend of Lincoln, taking advantage of this Presidential favor, sold prisoner releases to wealthy Confederate families for $250 each. The guards proved absolutely corrupt and eager for bribes. When the Chicago Police were brought in to clean up some of the corruption among guards, they used the opportunity to systematically rob the Confederate prisoners.

On August 18, 1863, Colonel Charles DeLand was made commander at Camp Douglas, bringing with him the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters. In reprisal for escape attempts and other infractions as a method of interrogation, he introduced several forms of torture, including hanging men by their thumbs for hours. Several died from this ordeal. He also introduced a torture called the “riding the horse” or “riding Morgan’s mule.” Prisoners were forced to sit for man hours on the narrow and sharpened edge of a horizontal two by four and suspended by supports four to twelve feet high. Guards often hung weighty buckets of dirt and rock on their feet to increase the pain, which often caused permanent disabilities.

The Union Army frequently promised to release Confederate prisoners, if they agreed to join the Union Navy or Army units fighting Indians in the West. Sergeant-major Oscar Cliett of the 55th Georgia Infantry reported to DeLand that his men rejected the offer to join the Union Navy, “as we couldn’t swim.” Mulligan would have laughed, but DeLand had Cliett chained in a dungeon for 21 days on bread and water.

In March 1864, after a tour of duty at Camp Douglas distinguished by corruption and mismanagement as well as cruelty, DeLand and his regiments returned to the field. In May, during the Wilderness Campaign in Virginia, he was badly wounded and captured. Ironically, he was given every courtesy as a prisoner of war by his Confederate captors.

In May 1864, Colonel Benjamin Sweet, who lost his position in the famous “Iron Brigade” for trying to undermine the commander of the 6th Wisconsin, and who had been undermining DeLand for months, became commandant of Camp Douglas. The cruelties continued unabated, and rations were reduced even more, but the appearance of the camp improved. During the 1864 election campaign Sweet also managed to persuade Lincoln and the War Department to put Chicago, then a town of 110,000, under martial law to prevent a prison uprising supported by Southern sympathizers in Chicago. More than 100 civilians were arrested and jailed for criticizing Lincoln policies or on the mere suspicion of Southern sympathies without the benefit of a hearing or trial. Twelve died in prison before the end of the war. The uprising threat was vastly exaggerated and largely fabricated, but Sweet was promoted to Brigadier General in December for saving Chicago. At the end of the war, he received a commendation for a job well done.

Many people of Chicago and many Christian churches in the area offered relief to the prisoners at Camp Douglas. Until the Union government put a stop to the practice, many prominent people and local churches gave time, financial aid, and medicines to assist the post surgeon in the care of the sick and destitute prisoners. The famous evangelist D.L Moody was brought in to preach on several occasions. Some Confederate prisoners, however, complained of the high propaganda content of sermons by other preachers.

At the end of the war the Confederate prisoners were offered transportation home by train, if they signed the Union loyalty oath. Otherwise, they would have to walk home. Most of the prisoners at Camp Douglas elected to walk home. By July 1865, the last POW had left Camp Douglas. The disgraceful history of Camp Douglas has been largely forgotten. Nothing remains of the camp but a monument and 6,000 graves at the nearby Oak Woods Cemetery.

Inscription on the Confederate Mound monument, located at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago. Nearly 6000 Confederate soldiers that died at Camp Douglas Union prison camp are buried here, 4200 are listed on the monument, the remaining are unknown soldiers. Photo courtesy of Matt Hucke.

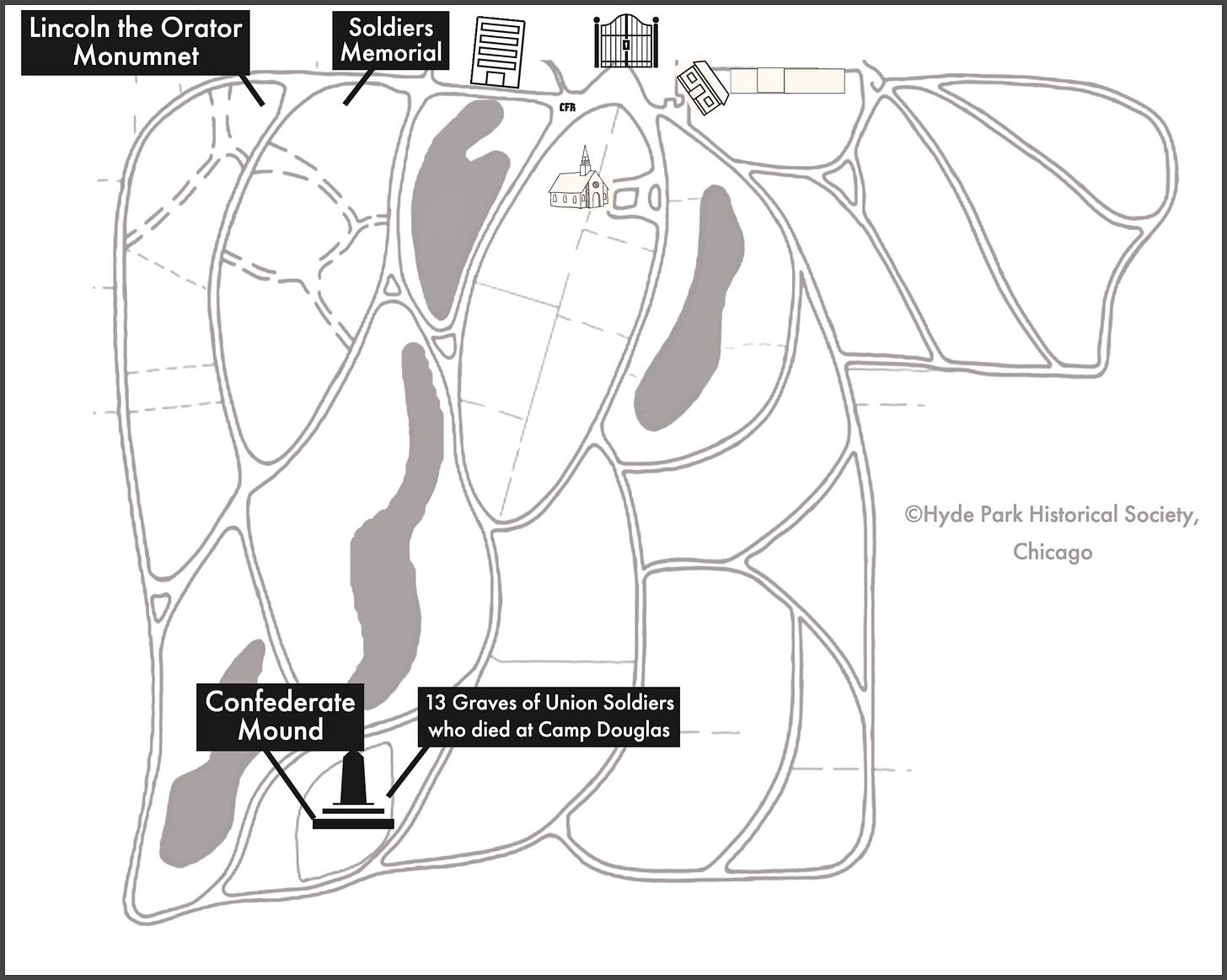

Oak Woods is the home to the largest mass grave of Confederate Soldiers in the United States as well as to hundreds of soldiers who served in the Union Army. There are 3 prominent Civil War monuments which were constructed over the years.

**The Soldier’s Memorial is a tribute to the Union Soldiers who served in the Civil War. It was erected in 1876 by the Board of Managers of the Chicago Soldier's Home.

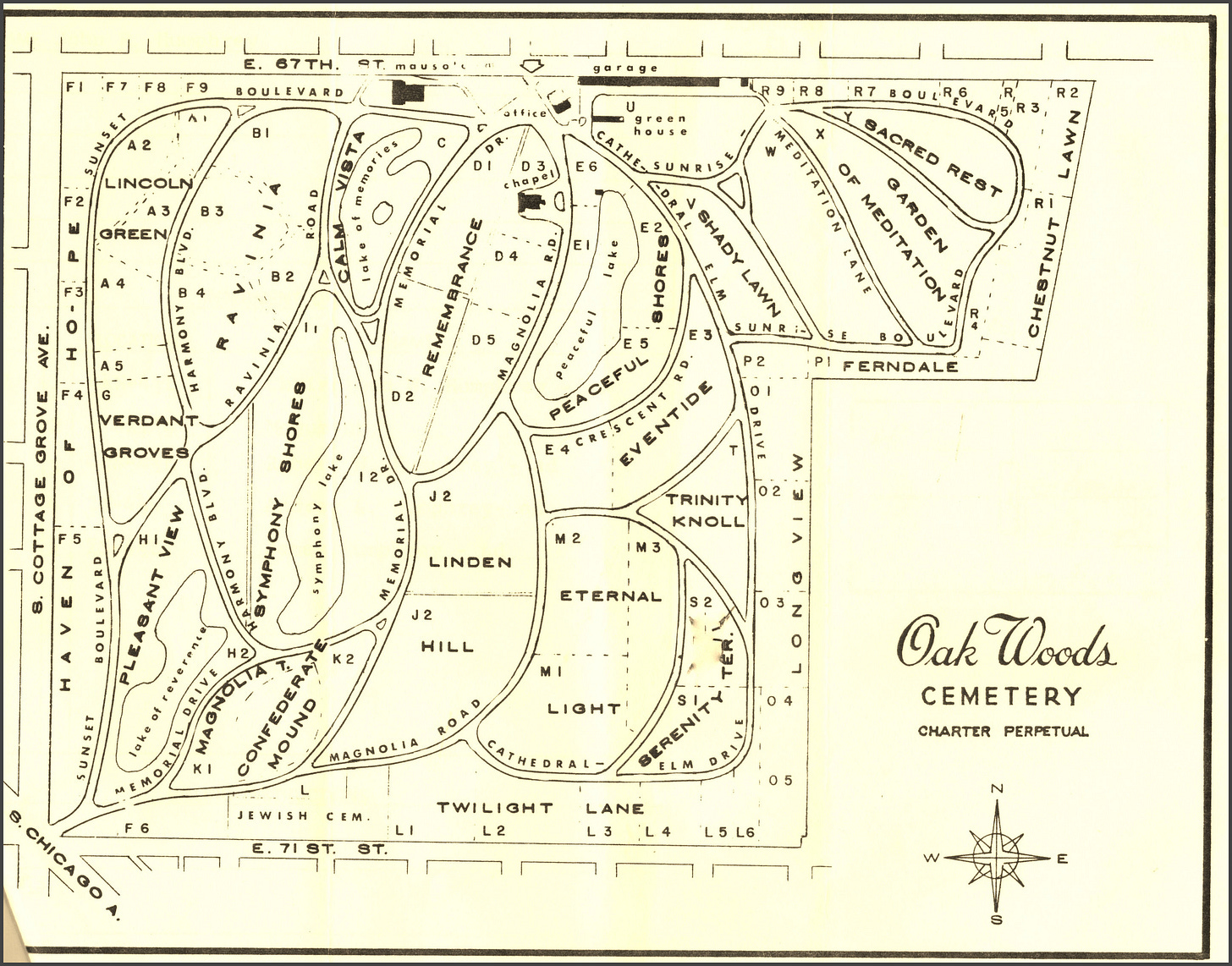

The Confederate Mound is a large granite monument in the southwest corner of the cemetery that memorializes the more than 4,000 Confederate soldiers who perished while imprisoned at Chicago’s Camp Douglas during the Civil War.

Located in what is the present-day Bronzeville neighborhood, politician Stephen Douglas leased the land for Camp Douglas to the US government for military purposes during the war. Originally used for the training of Union soldiers, Camp Douglas became a significant military prison as the war went on, housing nearly 26,000 soldiers through the duration of the conflict. Conditions at the camp made diseases such as smallpox easy to spread between prisoners, resulting in a significant number of deaths. Deceased prisoners were buried on the grounds of the camp as well as in Chicago’s old City Cemetery, located in modern-day Lincoln Park, but at the end of the war the US government bought a portion of land in Oak Woods cemetery to serve as the resting place for these Confederate soldiers.

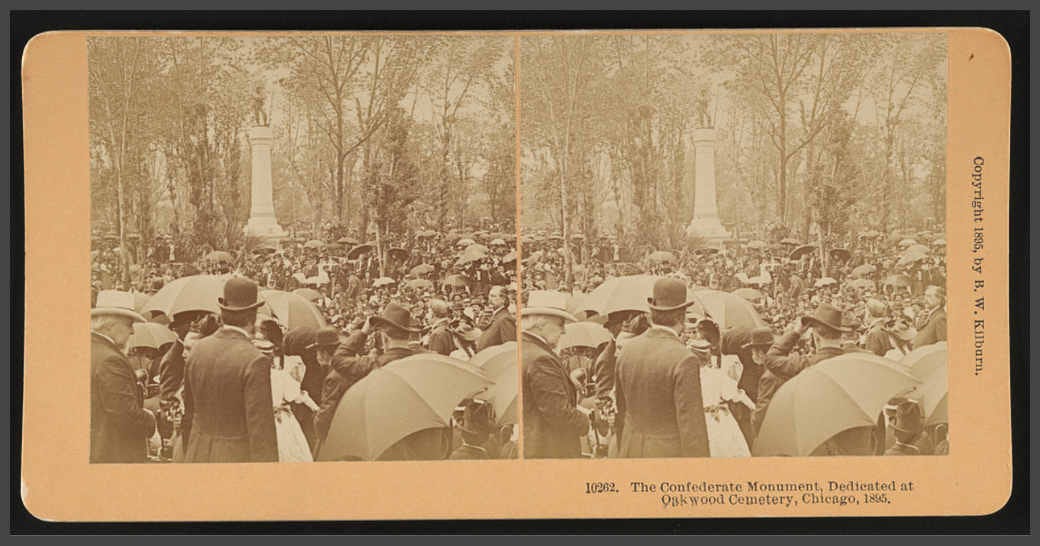

In 1887, more than 20 years after the initial re-interment, the War Department approved a proposal by former-Confederates to build a monument to the fallen soldiers at the burial site in Oak Woods. Under the creative and financial supervision of former Confederate Officer John C. Underwood, the Mound project was completed in 1895, and its dedication attracted a crowd of over 100,000 people. The main feature of the monument is a statue of a Confederate soldier, inspired by the painting “Appomattox” by John A. Elder.

Nearby the statue are cannonballs stacked in pyramids. In 1911, additional construction at the site raised the mound and added plaques that contain the names of individuals known to have died as prisoners at Camp Douglas.

Some historians point to the Confederate memorialization at Oak Woods cemetery as evidence of an evolving memory of the Civil War in succeeding generations. In Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory David W. Blight identifies the dedication of the Confederate Mound at Oak Woods cemetery as representing a shift away from an emancipationist memory on the war that centered the ending of slavery, with a reconciliationist’s memory that emphasized the valor of soldiers on both sides, while minimizing the causes of the conflict. For Blight, the emancipationist vision of the Civil War, synonymous with Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, understood the conflict as a sacred fight aimed at an American “rebirth” with the collapse of slavery. However, in service to the nation’s deep need to heal, Blight reveals how silences around slavery and Reconstruction served the reconciliationist narrative that followed the conflict. Celebrating the heroism of Confederate soldiers in ceremonies and monuments such as those at Oak Woods, may have provided a sense of reunion at the expense of the ideals of the conflict.

Some view the Confederate Mound as unique in character as a monument to the suffering of everyday Confederate soldiers, without commenting on their cause and the Mound is still annually honored by organizations such as the Illinois chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

The monument’s placement in Oak Woods, a previously segregated cemetery, stands in contrast to its other major legacy: a resting place for significant Black Chicagoans, including civil rights leaders. The fraught juxtaposition of this monument dedicated to soldiers who fought to preserve slavery with figures such as Ida B. Wells, Harold Washington and Lyman Trumbull, an architect of the 13th amendment to end slavery, makes Oak Woods a rich space for contemporary cultural conversations related to Confederate monuments and memorialization. Oak Woods demonstrates the way that different historical narratives can converge within a physical space, creating tension, but also the opportunity to see history as something that is not fixed, but always evolving.

Their cemetery burial records are not online. They are at the cemetery office. For over the phone support, the staff only has an alphabetized list with names and date of death. They cannot sort or otherwise analyze the data. If you visit the office, unless you are a family member you are not allowed to look at the record due to privacy guidelines. The only information provided to the general public is the location of the grave. To obtain this information you must have the deceased's name and year of burial. The burial record may (but will not always) contain the person's name, year of burial, age at burial, owner of the grave, section, lot, and grave number. They can sometimes tell you if there is a marker (gravestone, plaque, etc.). However, their records will in some cases indicate there isn't one when there is. So always check the actual grave since the records can be incomplete or in error. Please note this is not the staff's fault. It's simply a part of historic record keeping. Maps of the cemetery, section and lot are provided at the cemetery office if you visit.

Reference Reading:

“Riding the horse or “riding Morgan’s mule” were devices used during the American Civil War by Union guards against their Confederate prisoners:

There were some of our poor boys, for little infraction of the prison rules, riding what they called Morgan's mule every day. That was one mule that did the worst standing stock still. He was built after the pattern of those used by carpenters. He was about fifteen feet high; the legs were nailed to the scantling so one of the sharp edges was turned up, which made it very painful and uncomfortable to the poor fellow especially when he had to be ridden bareback, sometimes with heavy weights fastened to his feet and sometimes with a large beef bone in each hand. This performance was carried on under the eyes of a guard with a loaded gun and was kept up for several days; each ride lasting two hours each day unless the fellow fainted and fell off from pain and exhaustion. Very few were able to walk after this hellish Yankee torture but had to be supported to their barracks.

— Milton Asbury Ryan, Co. G, 8th MS Regiment

And so I know of, but a lot about Andersonville but not CampDouglas or the other northern prison camps. Of course that they existed is no surprise. That I lived close enough to Chicago to go there a few times a week and I still never heard of this prison...

Apparently I discovered it is an historic site,like Andersonville. According to a quick Google search over 100,000 people visit Andersonville each year,Camp Douglas struggles and seldom achieves a thousand visitors.

Yes, Andersonville was the largest and most well-known Confederate prisoner camp. Camp Douglas was known for being the most cruel of the Uniin POW camps. In any book distributed by the War Department, they've will debunk any reference to cruelty. You will find on many websites they claim it's a myth. Again, the victors wrote the history, but they can't hide it forever!