Fort Sumter's Surrender and the North's Reaction

Two views: An eyewitness account of the bombardment of Fort Sumter from the notes of Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee, C. S. A., and the North's view as told by Jacob D. Cox, Major-General.

The Confederate Side at Fort Sumter: From the notes of Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee, C. S. A. For The Century War Book, March 26, 1894

Captain, C. S. A., and Aide-de-camp to General Beauregard during the bombardment of Fort Sumter.

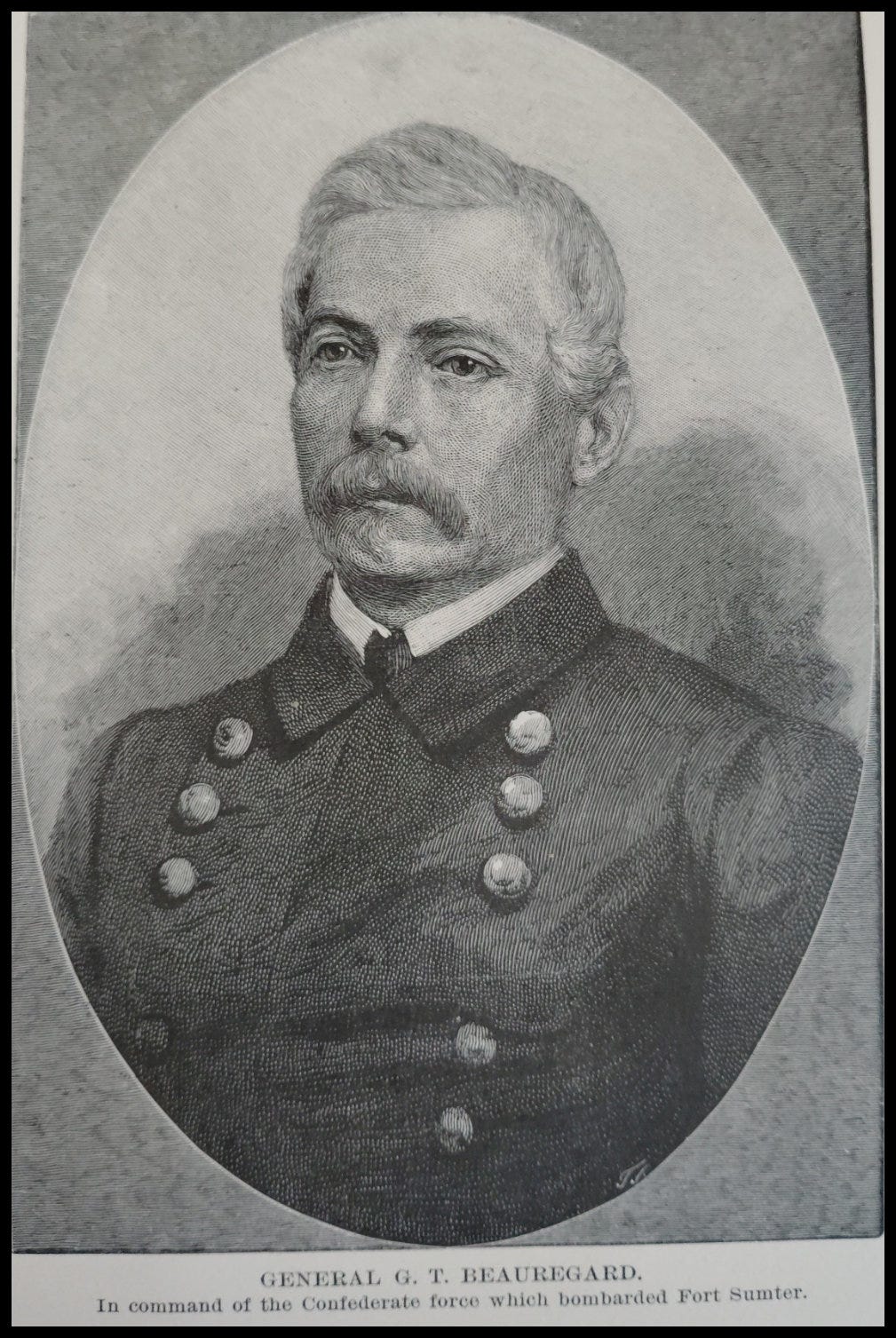

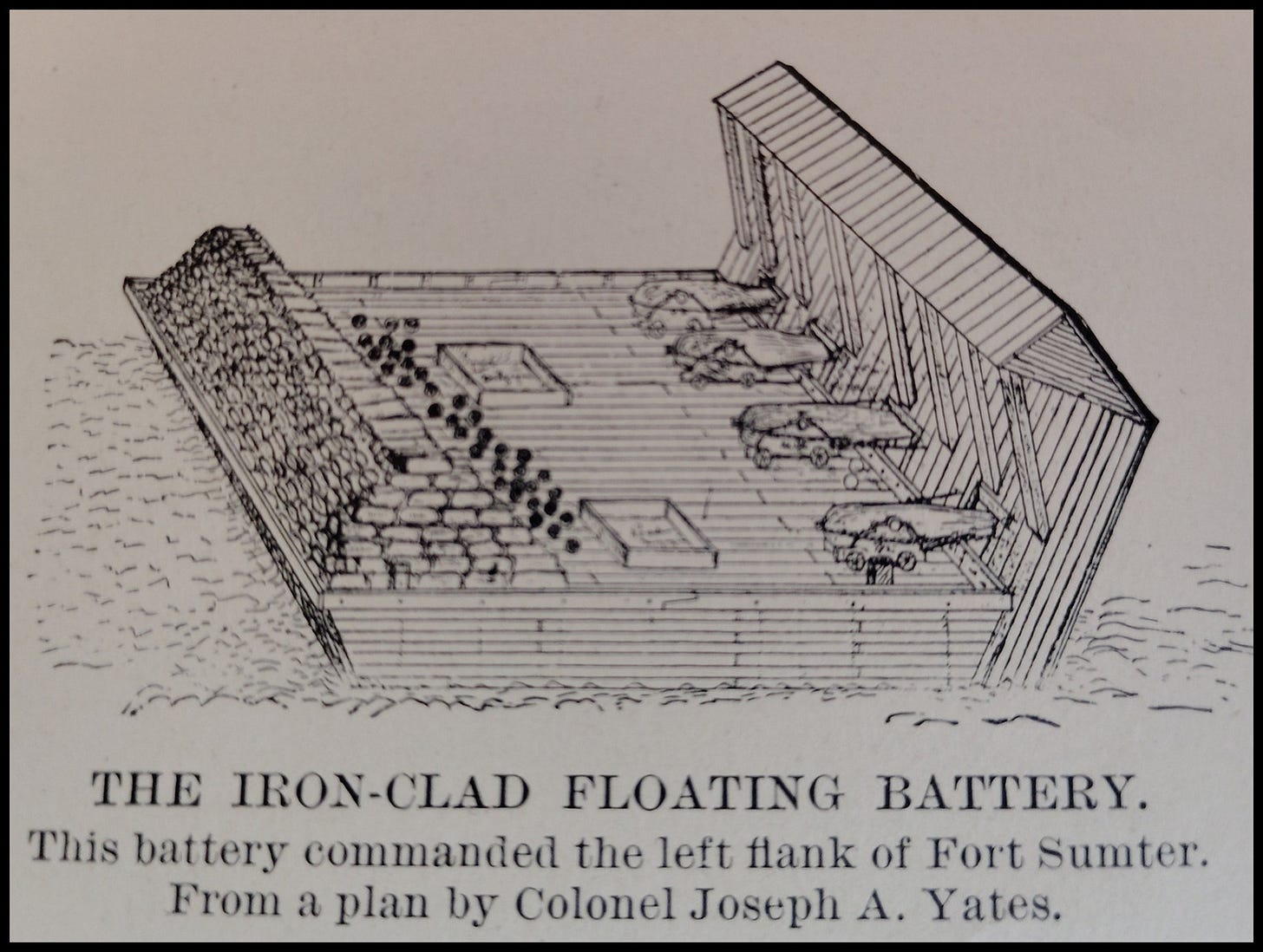

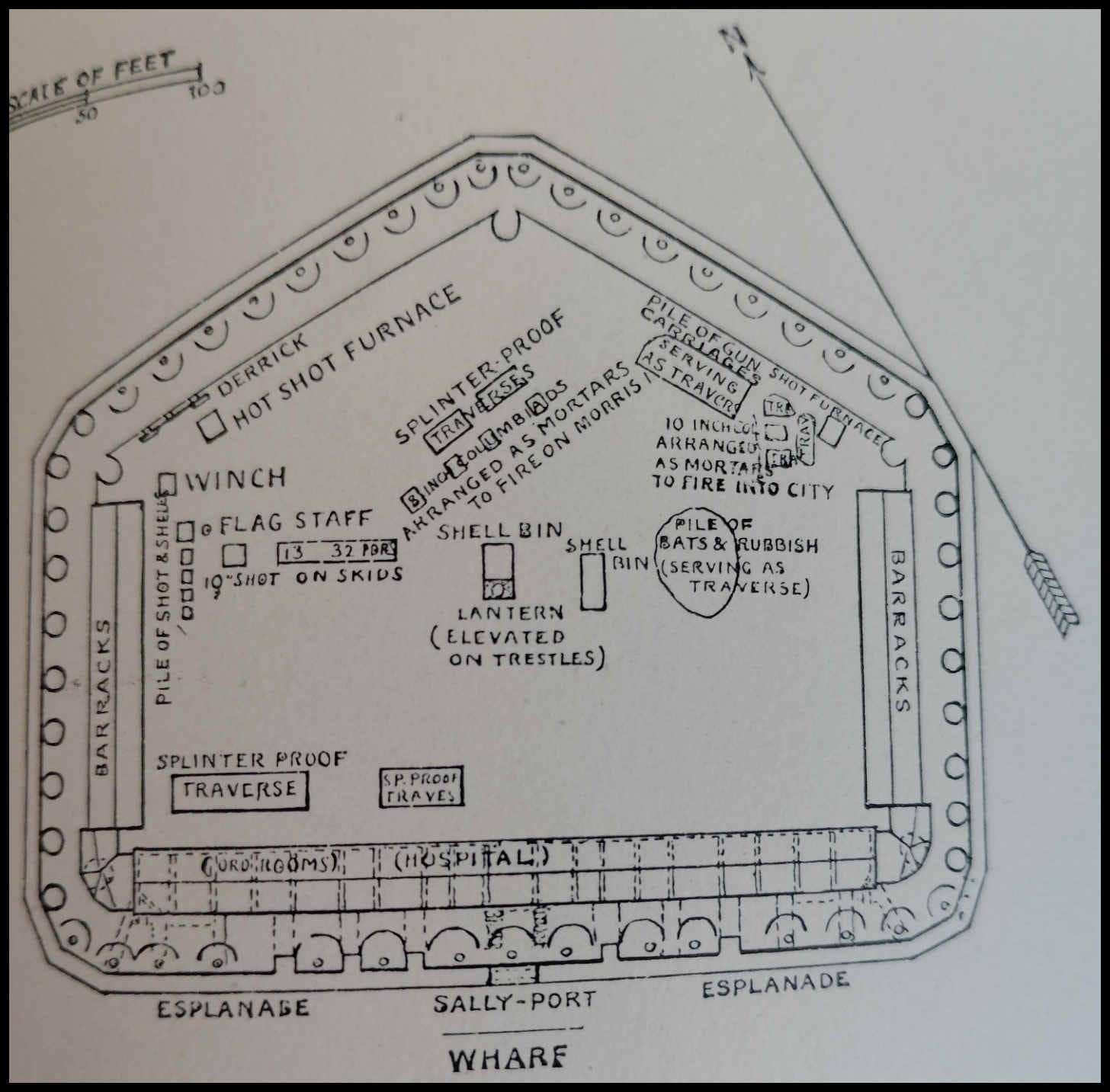

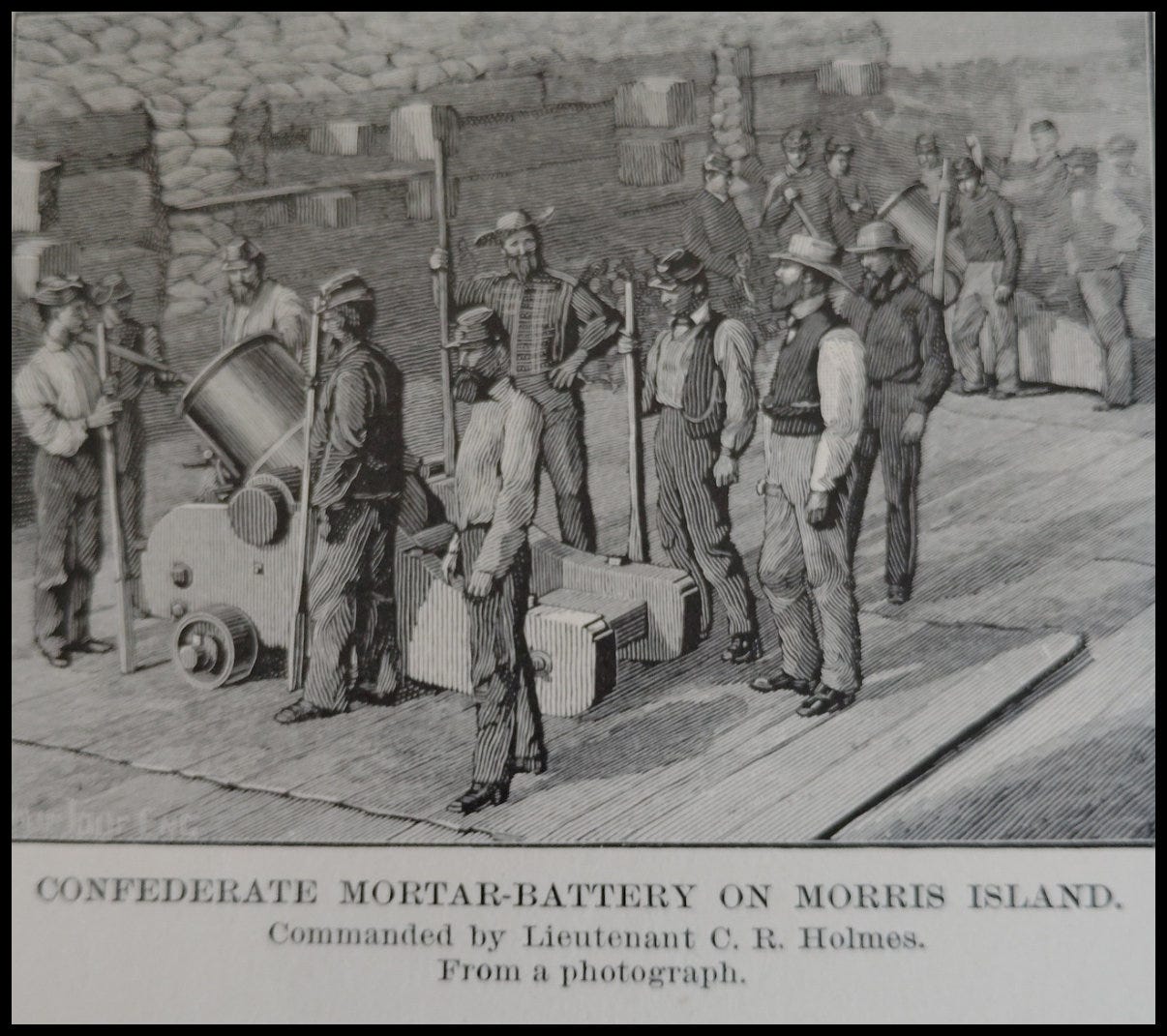

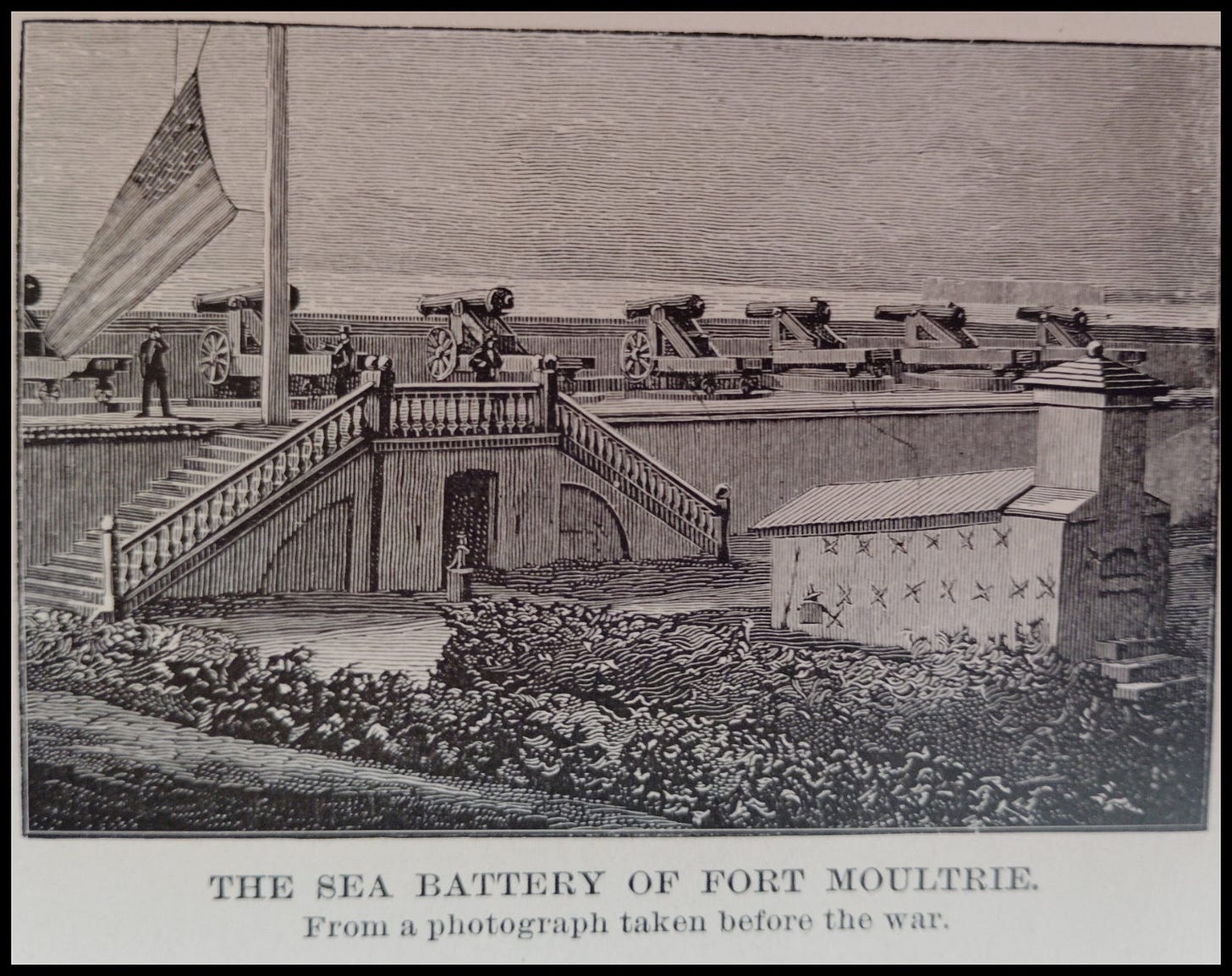

After the evacuation of Fort Moultrie, Major Anderson was not permitted by the South Carolina authorities to receive any large supply of provisions, yet he did receive daily mail, and fresh beef and vegetables from the city of Charleston and was unmolested at Fort Sumter. He continued continuously to strengthen the fort. The military authorities of South Carolina, and afterward of the Confederate States, took possession of Fort Moultrie, Castle Pickney, the arsenal, and other Unites States property in the vicinity. They also remounted the guns at Fort Moultrie, and constructed batteries on Sullivan’s, Morris and James Islands, and at other places, looking at the reduction of Fort Sumter if it should become necessary; meantime leaving no stone unturned to secure from the authorities at Washington a quiet evacuation of the fort. Several arrangements to accomplish this purpose were almost reached but failed. Two attempts were made to reinforce and supply the garrison; one by the steamer Star of the West, which tried to reach the fort on January 9th, 1861, and was driven back by a battery on Morris Island, manned by South Carolina troops; the other just before the bombardment of Sumter on April 12th. The feeling the Confederate authorities had was that a peaceful issue would finally arrive, but they had a fixed determination to use force, if necessary to occupy the fort. They did not intend or desire to take the initiative if it could be avoided. So soon, however, as it was clearly understood that the authorities in Washington had abandoned any peaceful views and would assert the power of the United States to supply Fort Sumter, General G. T. Beauregard, the commander of the Confederate forces at Charleston, in obedience to the command of his Government at Montgomery, proceeded to reduce the fort. His arrangements were about complete, when on April 11th he demanded of Major Anderson the evacuation of Fort Sumter. He offered to transport Major Anderson and his command to any port in the United States; and to allowed him to move out of the fort with company arms and property, and all private property, and to salute his flag in lowering it. This demand was delivered to Major Anderson at 3:45 P.M., by two aides-de-camp of General Beauregard, James Chestnut Jr., and Stephen D. Lee. At 4:30 P.M. he handed then his reply, refusing to accede to the demand; but added, “Gentlemen, if you do not batter the fort to pieces about us, we shall be starved out in a few days.”

The reply of Major Anderson was put in General Beauregard’s hands at 5:15 P.M., and he was also told of this informal remark. Anderson’s reply and remark was communicated to the Confederate authorities at Montgomery. The Secretary of War, L. P. Walker, replied to Beauregard as follows:

“Do not desire needlessly to bombard Fort Sumer. If Major Anderson will state the time at which, as indicated by him, that he will not evacuate, and agree that in the meantime he will not use his guns against us, unless ours should be employed against Fort Sumter, you are authorized, thus, to avoid the effusion of blood. If this, or its equivalent, be refused, reduce the fort as your judgement decides to be most practicable.”

The same aides bore a second communication to Major Anderson, based on the above instructions, which was placed in his hands at 12:45 A.M., April 12th. His reply indicated that he would evacuate the fort on the 15th, provided he did not in the meantime receive contradictory instructions from his Government of additional supplies, but he declined to agree not to open his guns upon the Confederate troops, in the event of any hostile demonstration on their part against his flag. Major Anderson made every possible effort to retain the sides till daylight, making one excuse and then another for not replying. Finally, at 3:15 A.M., he delivered his reply. In accordance with their instructions, the sides read it and, finding it unsatisfactory, gave Major Anderson this notification:

“Fort Sumter, South Carolina, April 12th, 1861, 3:20 A.M.

Sir:

By authority of Brigadier General Beauregard, commanding the Provisional Forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time.

We have the honor to be very respectfully.

Your obedient servants,

James Chestnut, Jr., Aide -de-camp.

Stephen D. Lee, Captain C. S. Army, Aide-de-camp.”

The above note was written in one of the casements of the fort, and in the presence of Major Anderson and several of his officers. On receiving it he was much affected. He seemed to realize the full impact of the consequences, and the great responsibility of his position. Escorting, James Chestnut, Jr., and Stephen D. Lee to the boat at the wharf, he cordially pressed their hands in farewell, remarking, “If we never meet in this world again, God grant that we may meet in the next.”

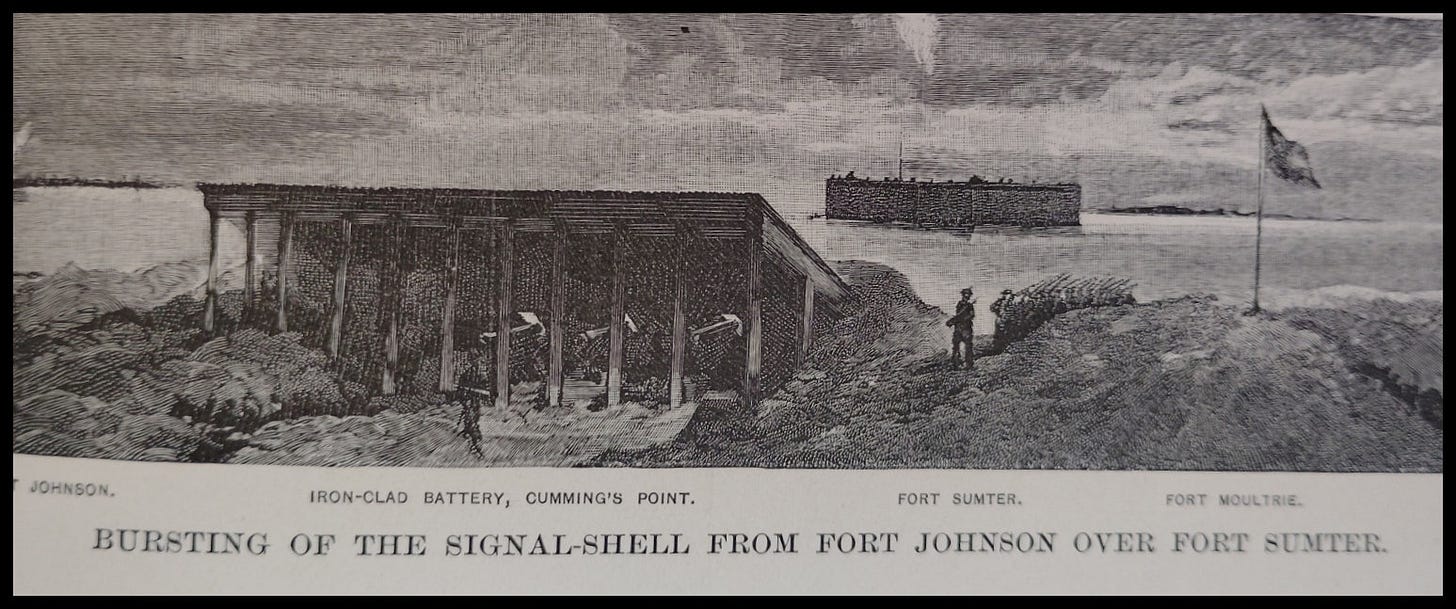

The boat containing the two aides and also Roger A. Pryor, of Virginia, and A. R. Chisolm, of South Carolina, who were also members of General Beauregard’s staff, went immediately to Fort Johnson on James Island, and the order to fire the single gun was given by Captain George S. James, commanding the battery at that point. It was then 4:00 A.M. Captain James at once aroused his command and arranged to carry out the order. He was a great admirer of Roger A. Pryor, and said to him, “You are the only man to whom I would give up the honor of firing the first gun of the war;” and he offered to allow him to fire it. Pryor, on receiving the offer, was very much agitated. With a husky voice he said, “I could not fire the first gun of the war.” His manner was almost similar to that of Major Anderson as the aides left him a few minutes before on the wharf at Fort Sumter. Captain James would allow no one else but himself to fire the gun.

The boat with the aides of General Beauregard left Fort Johnson before arrangements were complete for the firing of the gun, and laid on its oars, about one-third the distance between the fort and Sumter, there to witness the firing of “the first gun of the war” between the States. It was fired from a ten-inch mortar at 4:30 A.M., April 12th, 1861. Captain James a skillful officer, and the firing of the shell was a success. It burst immediately over the fort, apparently about one hundred feet above. The firing of the mortar woke the echoes from every nook and corner of the harbor, and in this dead hour of night, before dawn, that shot was a sound of alarm that brought every soldier in the harbor to his feet, and every man, woman, and child in the city of Charleston from their beds. A thrill went through the whole city. It was felt that the Rubicon was passed. No one thought of going home; unfamiliar as their ears were to the appalling sounds, or the vivid flashes from the batteries, they stood for hours fascinated with the horror. After the second shell, the different batteries opened their fire on Fort Sumter, and by 4:45 A.M. the firing was general and regular. It was a hazy, foggy morning. About daylight, the boat with the sides reached Charleston, and they reported to General Beauregard.

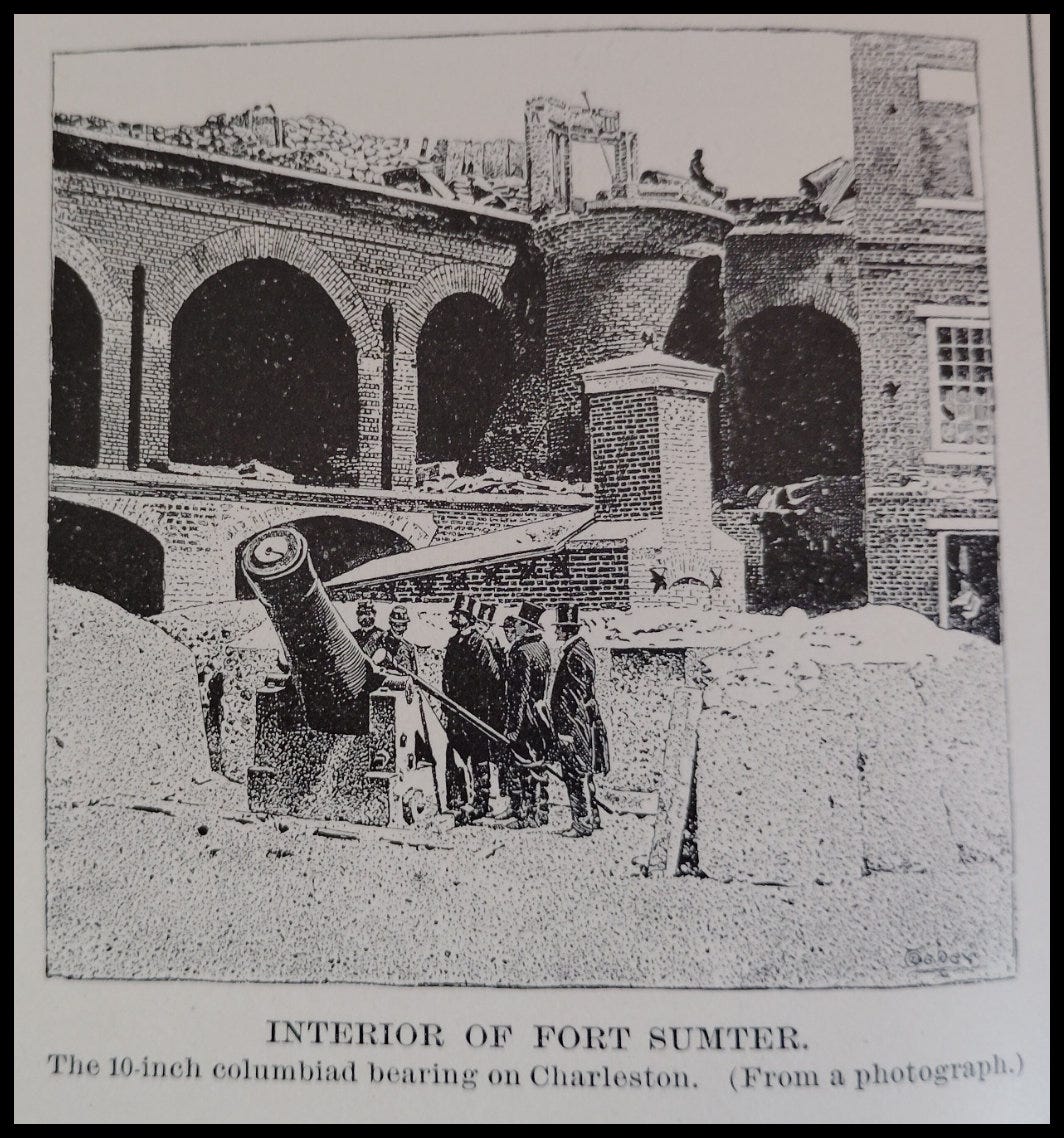

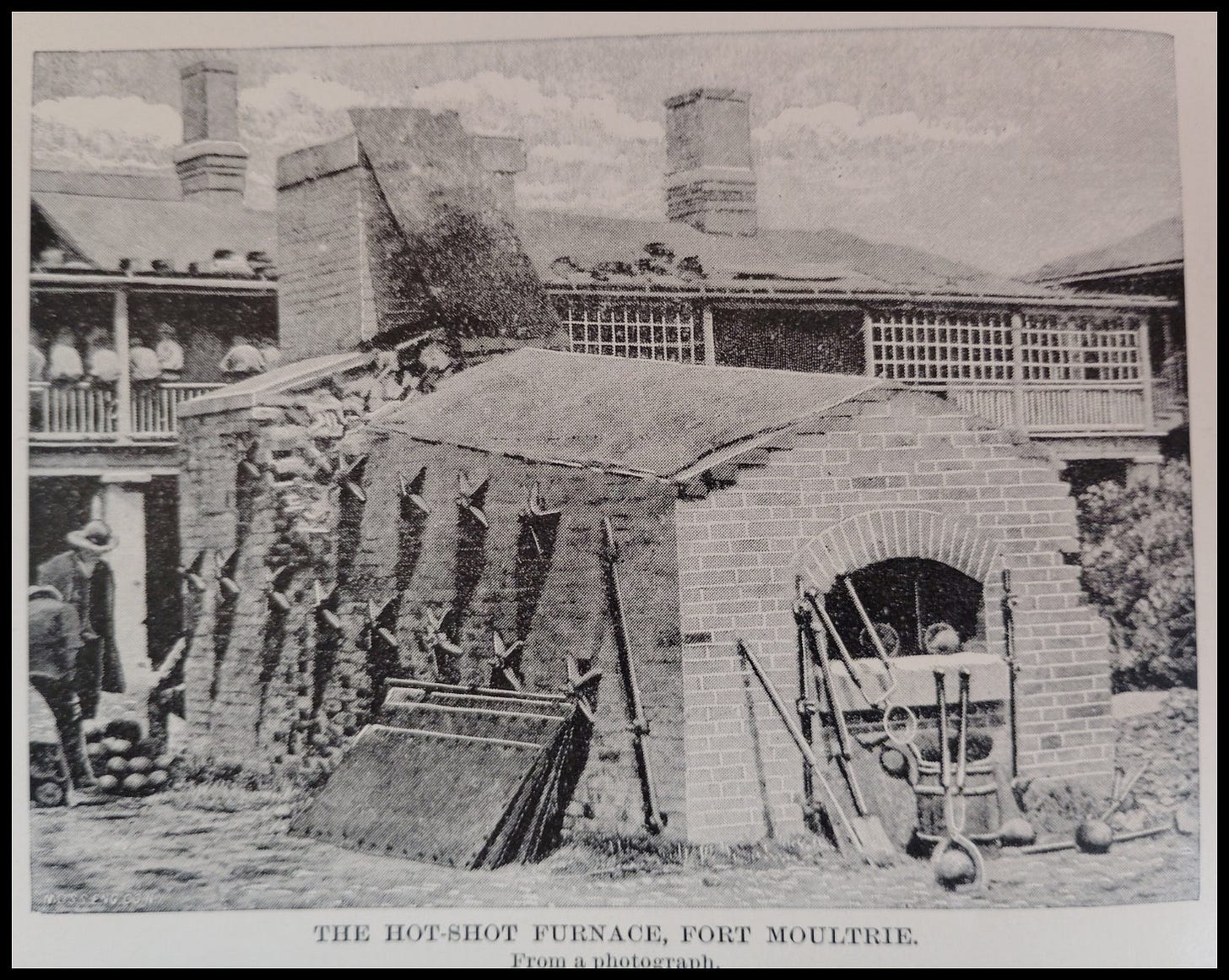

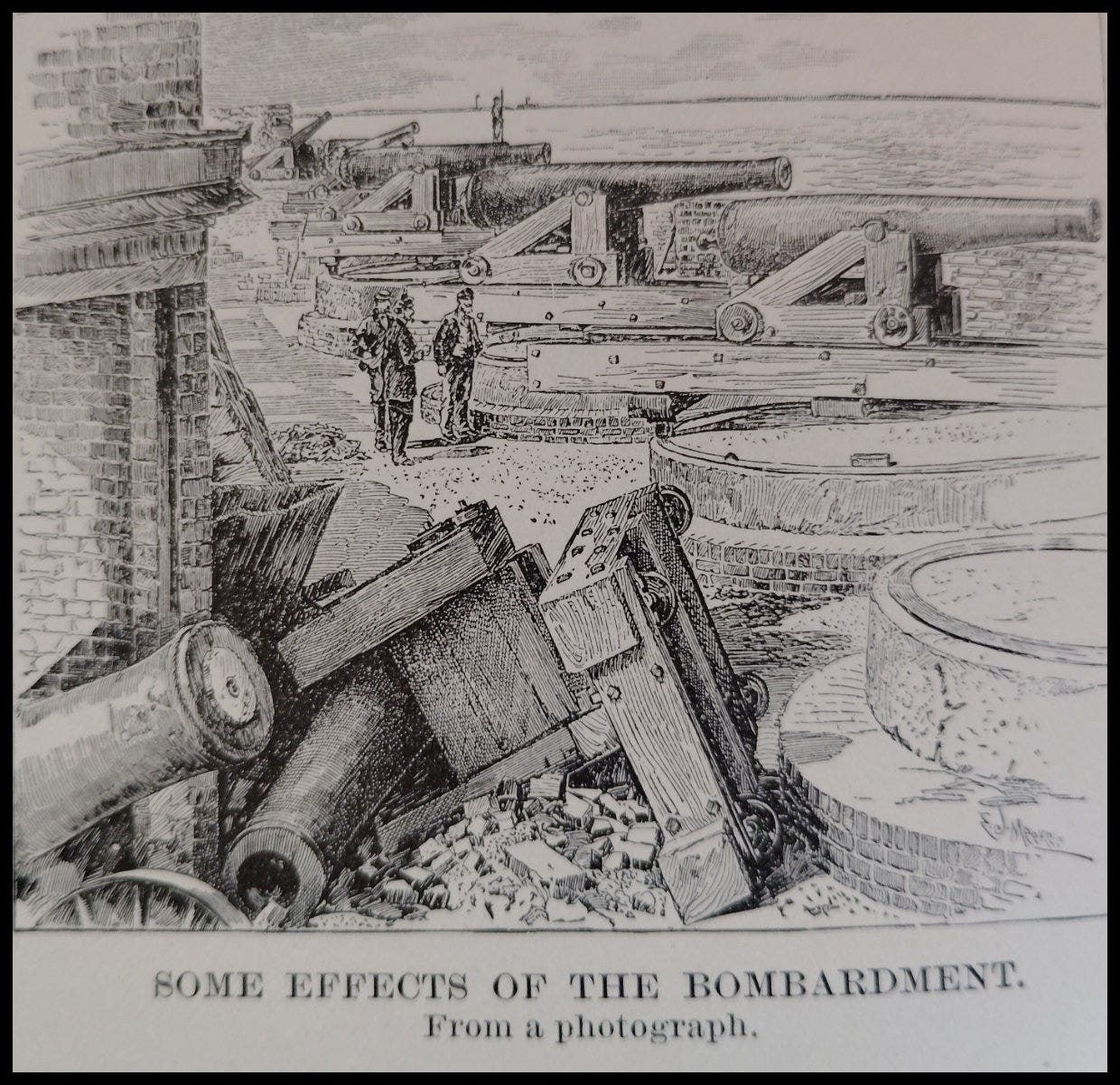

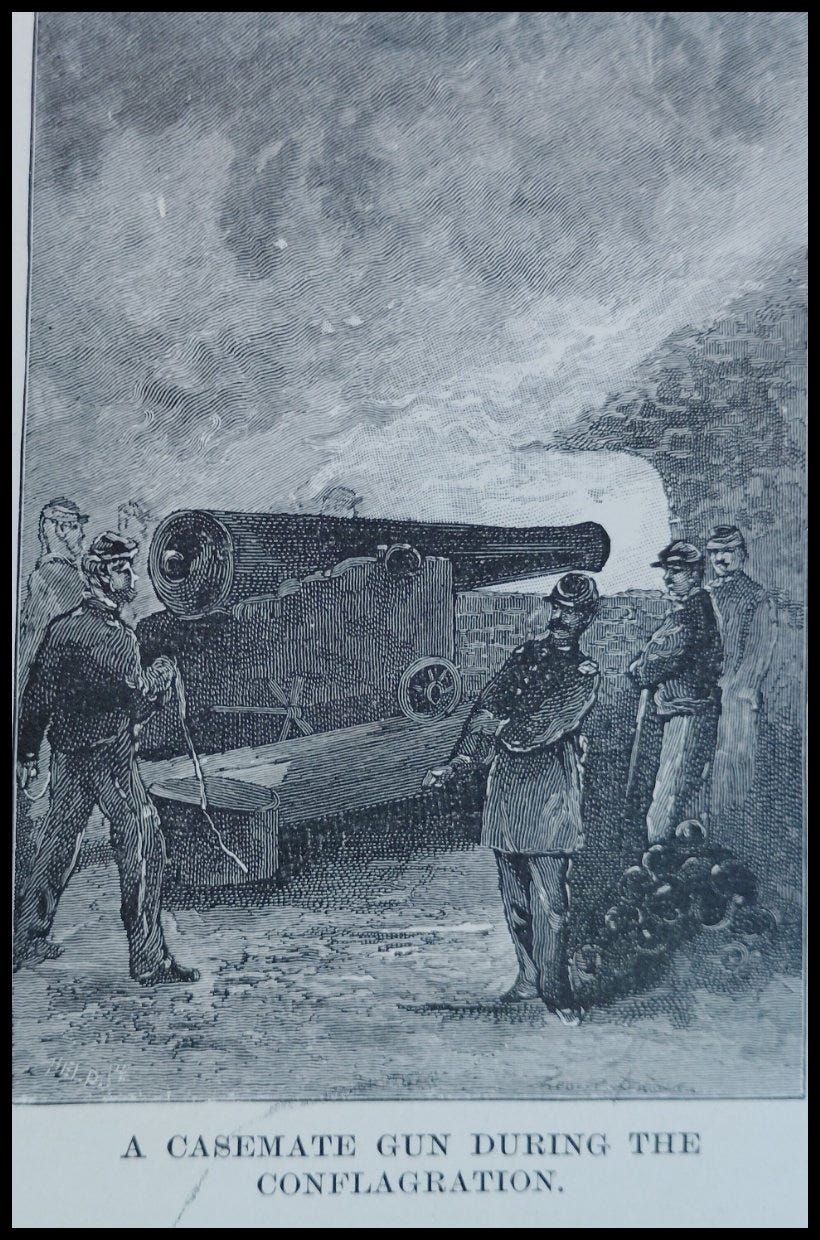

Fort Sumter did not respond with her guns till 7:30 A.M. The firing from this fort, during the entire bombardment, was slow and deliberate, and marked with little accuracy. The firing persisted uninterrupted on the 12th, and more slowly during the nights of the 12th and the 13th. No material change was noticed until 8:00 A.M. on the 13th, when the barracks in Fort Sumter were set on fire by hot shots from the guns of Fort Moultrie. As soon as this was discovered, the Confederate batteries redoubled their efforts, to prevent the fire from being extinguished. Fort Sumter fired at little, longer intervals, to enable the garrison to fight the flames. This brave action, under such a trying ordeal, aroused great sympathy and admiration on the part of the Confederates for Major Anderson and his gallant garrison; this feeling was shown by cheers whenever a gun was fired from Sumter. It was shown also by loud reflections on the “men-of-war” outside the harbor.

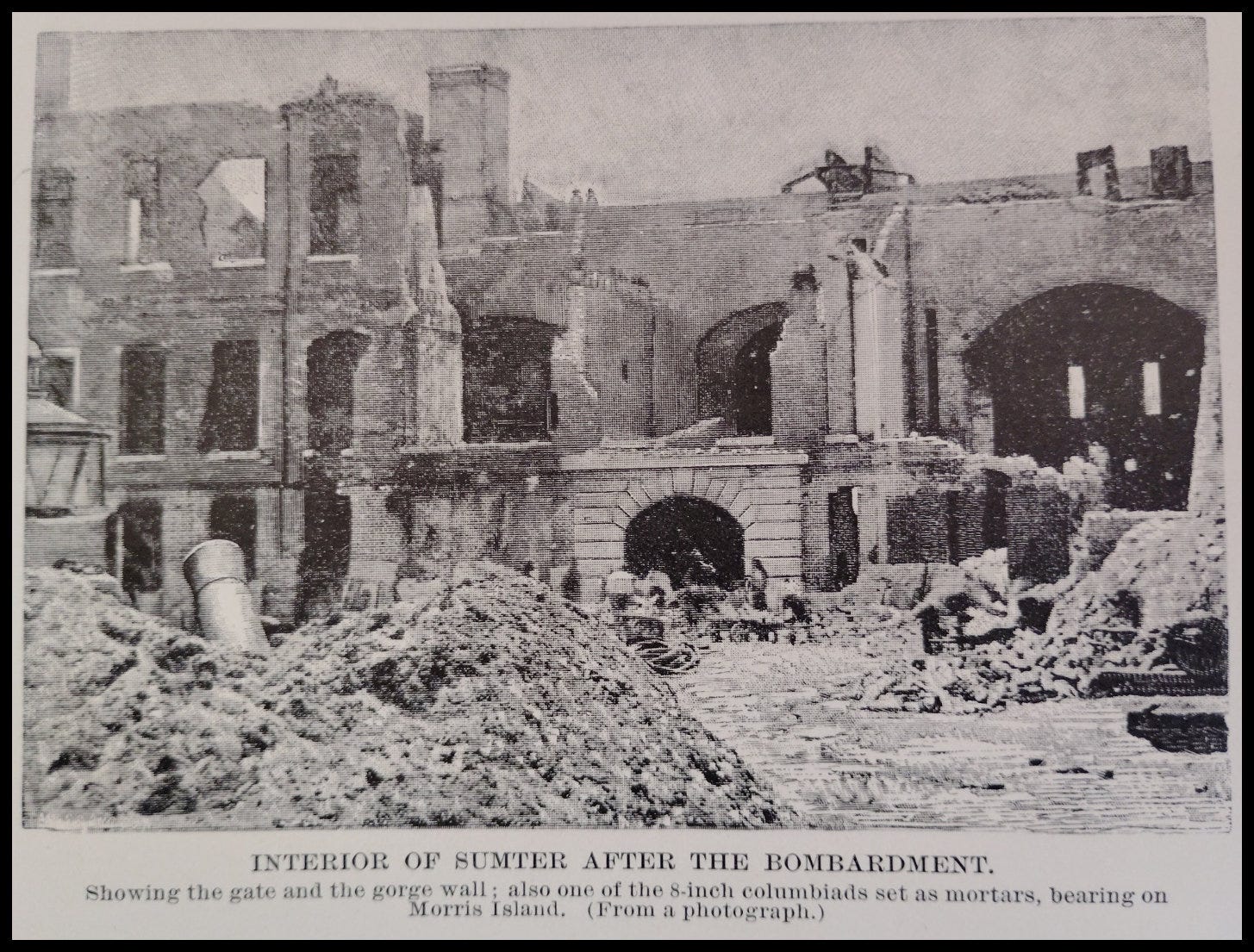

About 12:30 P.M. the flag-staff of Fort Sumter was shot down, but it would soon be replaced. As soon as General Beauregard heard that the flag was no longer flying, he sent three of his aides, William Porcher Miles, Roger A. Pryor, and Captain Stephen D. Lee, to offer, and also see if Major Anderson would receive or needed assistance in subduing the flames inside the fort. Before the aides reached it, they saw the United States flag again floating over it and began to return to the city. Before going far, however, they saw the Stars and Stripes replaced by a white flag. They turned around at once and rowed rapidly towards the fort. They were directed, from an embrasure, not to go to the wharf, as it was mined, and the fire was near it. The men were assisted through an embrasure and conducted to Major Anderson. Their mission being made known to him, he replied, “Present my compliments to General Beauregard, and say to him I thank him for his kindness, but need no assistance.” He further remarked that he had hoped the worst was over, and that the fire had settled over the magazine, and, as it had exploded, he thought the real danger was about over. Continuing, he said, “Gentlemen, do I understand you come direct from General Beauregard?” The reply was in the affirmative. He then said, “Why! Colonel Wigfall had just been here as an aide too, and by authority of General Beauregard, and proposed the same terms of evacuation offered on the 11th instant.” The men informed the major that they were not authorized to offer terms; that they were direct from General Beauregard, and that Colonel Wigfall, although an aide-de-camp to the general, had been detached, and had not seen the general for several days. Major Anderson at once stated, “There is a misunderstanding on my part, and I will at once run up my flag and open fire again.”

After consultation, they requested him not to do so until the matter was explained to General Beauregard, requesting Major Anderson to reduce writing his understanding with Colonel Wigfall, which he did. However, before they left the fort, a boat arrived from Charleston, bearing Major D. R. Jones, assistant adjutant-general on General Beauregard’s staff, who offered substantially the same terms to Major Anderson as those offered on the 11th, and also by Colonel Wigfall, which were now accepted.

Thus fell Fort Sumter, on April 13th, 1861. At this time fire was still raging in the barracks and settled steadily over the magazine. All egress was cut off except through the lower embrasures. Many shells from the Confederate batteries, which had fallen in the fort and had not exploded, as well as the hand-grenades used for defense, were exploding as they were reached by the fire. The wind was driving the heat and smoke down into the fort and into the casemates, almost causing suffocation. Major Anderson, his officers and men were blackened by smoke and exhaustion from the trying ordeal through which they had passed.

It was soon discovered, by conversation, that it was a bloodless battle; not a man had been killed or seriously wounded on either side during the entire bombardment of nearly forty hours. Congratulations were exchanged on so happy of a result. Major Anderson stated that he had instructed his officers only to fire on the batteries and forts, and not to fire on private property.

The terms of evacuation offered by General Beauregard were generous and were appreciated by Major Anderson. The garrison was to embark on the 14th, after running up and saluting the United States flag, and to be carried to the United States fleet. A soldier killed during the salute was buried inside the fort, the new Confederate garrison uncovering during the impressive ceremonies. Major Anderson and his command left the harbor, bearing with them the respect and admiration of the Confederate soldiers. It was conceded that he had done his duty as a soldier holding a most delicate trust.

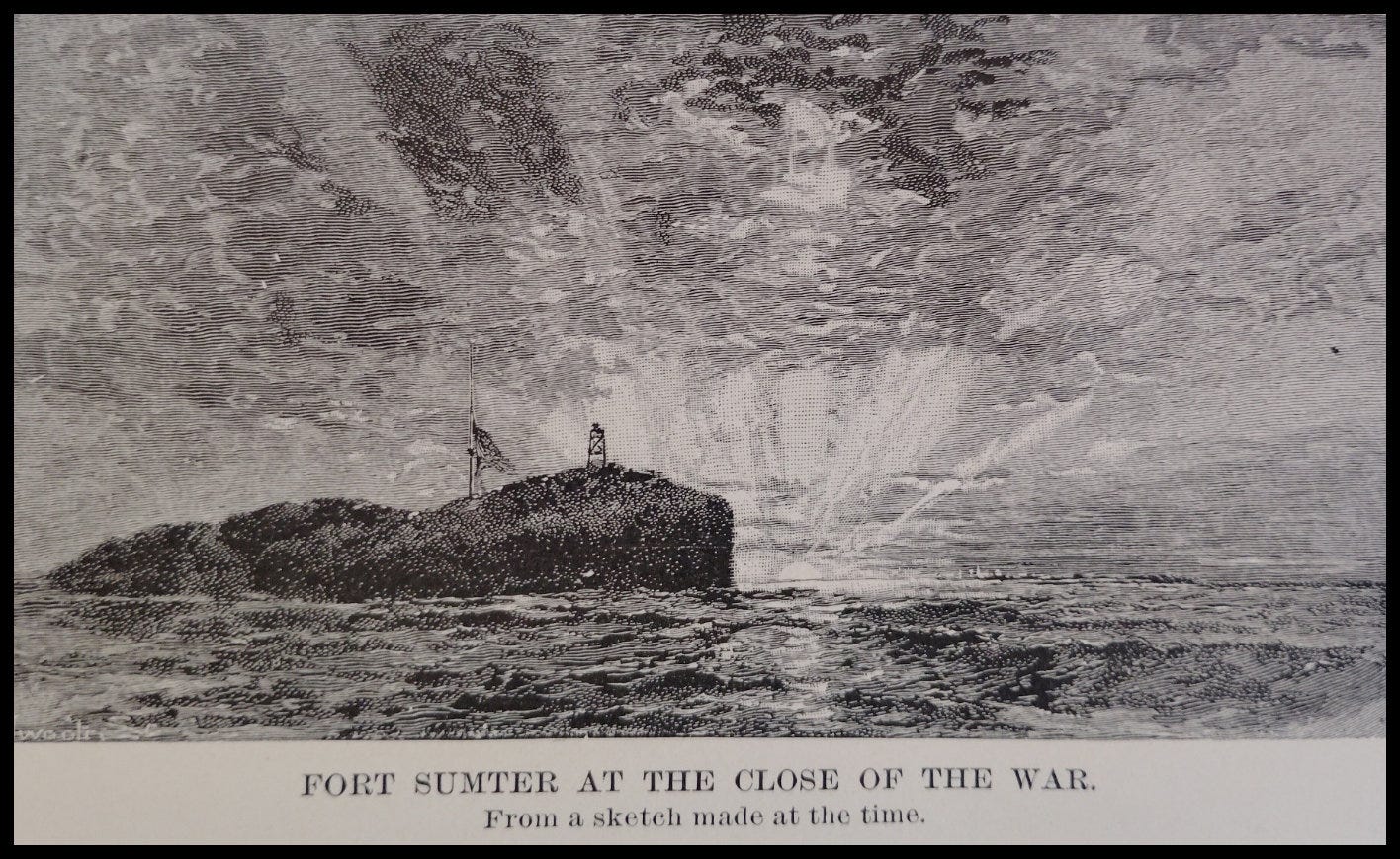

This first bombardment of Sumter was but its “baptism by fire.” During subsequent attacks by land and water, it was battered by the heaviest Union artillery. Its walls were completely crushed, but the tons of iron projectiles imbedded in its ruins added strength to the inaccessible mass that surrounded it and made it impregnable. It was never taken, but the operations of General Sherman, after his march to the sea, compelled its evacuation, and the Stars and Stripes were again raised over it on April 14th, 1865.

War Preparations in the North

By Jacob D. Cox, Major-General, U.S.V., Ex-Governor of Ohio, Ex-Secretary of the Interior. A member of the Ohio Senate at the outbreak of the war.

This article was published on March 26, 1894, The Century War Book, Peoples Pictorial Edition

On Friday, April 12th, 1861, the Senate of Ohio was in session, trying to go on in the ordinary routine of business, but with a sense of anxiety and strain which was caused by the troubles state of national affairs. The passage of “ordinances of secession” by one after another of the Southern States, and even the assembling of a provisional Confederate government at Montgomery, had not wholly destroyed the hope that some peaceful way out of their troubles would be found; yet the gathering of an army on the sands opposite Fort Sumter was really war, and if a hostile gun were fired, they knew it would mean the end of all efforts at arrangement. Hoping almost against hope that blood would not be shed, and that a pageant of military array and of a succession government would pass by, they tried to give it their thoughts to business; but there was no heart in it, and the “morning hour” lagged, for no one could work in earnest, and yet they were unwilling to adjourn.

Suddenly a Senator came into the lobby in an excited way, and, catching the chairman’s eye, exclaimed, “Mr. President, the telegraph announces that the secessionists are bombarding Fort Sumter!” There was a solemn and painful hush, but it was broken in a moment by a woman’s shrill voice from the spectator seats, crying, “Glory to God!” It startled everyone, almost as if the enemy was in the midst. But it was the voice of a radical friend of the slave, Abby Kelly Foster, who, after a lifetime of public agitation, believed that only through blood could his freedom be won, and who had shouted the fierce cry of joy that the question had been submitted to the decision of the sword. With many who were present, the gloomy thought that civil war had begun in our own land overshadowed everything else; this seemed too great a price to pay for any good, a scourge to be borne only in preference to yielding what was to us the very groundwork of our republicanism, the right to enforce a fair interpretation of the Constitution through the election of President and Congress.

The next day we learned that Major Anderson had surrendered, and the telegraphic news from all the Northern States showed plain evidence of a popular outburst of loyalty to the Union, following a brief moment of dismay. That was the period when the flag—The Flag—flew out to the wind from every housetop in our great cities, and when, in New York, wildly excited crowds marched the streets demanding that the suspected or the lukewarm should show the symbol of nationality as a committal to the country’s cause. He that is not for us is against us, was the deep, instinctive feeling.

A few days after the surrender at Sumter, Stephen A. Douglas passed through Columbus, on his way to Washington, and, in response to the calls of a spontaneous gathering of people, spoke to them from the window of his bedroom in the hotel. There had been no thought for any of the common surroundings of a public meeting. There were no torches, no music. A dark mass of men filled full the dimly lit street and called for Douglas with an earnestness of tone wholly different from the enthusiasm of common political gatherings. He came half-dressed to his window, and, without any light near him, spoke solemnly to the people upon the terrible crisis which had come upon the nation. Men of all parties were there; his own followers to get some light as to their duty; the Breckinridge Democrats ready, most of them, repentantly to follow a Northern leader now that their Southern associates were in armed opposition to the Government. The Republicans were eager to know whether so potent an influence was to be unreservedly on the side of the nation. I remember well the serious solicitude with which I listened to his opening statements as I leaned against the railing of the State House park, trying in vain to see more than a dim light outline of the man as he stood at the unlighted window. His deep, sonorous tones rolled down through the darkness from above us, an earnest, measured voice, the more solemn, the more impressive, because we could not see the speaker, and it came to us literally as “a voice in the night,”—the night of our country’s unspeakable trial. There was no uncertainty in his tone; the Union must be preserved, and the insurrection must be crushed. He pledged his hearty support to Mr. Lincoln’s administration in doing this; other questions must stand aside till the national authority should be everywhere recognized. I do not we greatly cheered him—it was rather, a deep Amen that went up from the crowd. We weren’t home breathing more freely in the assurance we now felt that, for a time at least, no organized opposition to the Federal Government and its policy of coercion could be formidable in the North.

Yet the situation hung upon us like a nightmare. Garfield and I were lodging together at the time, our wives being kept at home by family cares, and when we reached our little sitting room, after an evening session of the Senate, we often found ourselves involuntarily groaning, “Civil war in our land!” The shame, the folly, the outrage, seemed too great to believe, and we half hoped to awake from it as from a dream. Among the painful remembrances of those days is the ever-present weight at the heart which never left me till I found relief in the active duties of camp life at the close of the month. I went about my duties (and I am sure most of those with whom I associated did the same) with the half-choking sense of grief I dared not think of; like the one who is dragging himself to the ordinary labors of life from some terrible and recent bereavement.

We talked of our personal duty, and though both Garfield and myself had young families, we were agreed that our activity in the organization and support the Republican party made the duty of supporting the Government by military service come peculiarly home to us. He was, for the moment, somewhat trammeled by his half-clerical position, but he very soon cut the knot. My own path seemed unmistakenly plain. He, more careful for his friend than for himself, urged upon me his doubts whether my physical strength was equal the strain that would be put upon it. “I,” said he, “am big and strong, and if my relations to the church and the college can be loosened, I shall have no excuse for not enlisting; but you are slender and will break down.” It is true I then looked slender of a man of six feet high; yet I had confidence in the elasticity of my constitution, and the result justified me, while it showed how liable one is to mistake in such things. Garfield found that he had a tendency to weakness of the alimentary system, which broke him down on every campaign in which he served and led to his retiring from the army at the close of 1863. My own health, on the other hand, was strengthened by outdoor life and exposure, and I served to the end with growing physical vigor.

When Lincoln issued his first call for troops, the existing laws made it necessary that these should be fully organized and officered by several States. Then, the treasury was in no condition to bear the burden of war expenditures, and, till Congress could assemble, the President was forced to rely on the States for means to equip and transport their own men. This threw upon the governors and legislature of the loyal States responsibilities of a kind wholly unprecedented. A long period of profound peace had made every military organization seem almost farcical. A few independent companies formed the merest shadow of an army, and the State militia proper was only a nominal thing. It happened, however, that I held commission as brigadier in the State militia, and my intimacy with Governor Dennison led him to call upon me for such assistance as I could render in the first enrollment and organization of the Ohio quota. Arranging to be called to the Senate chamber when my vote might be needed, I gave my time chiefly to such military matters as the governor appointed. Although, as I have said, my military commission had been a nominal thing, and in fact I had never worn a uniform, I had not wholly neglected theoretic preparation for such work. For some years, the possibility of a war of secession had been one of the things which were forced upon the thoughts of reflecting people, and I had given some careful study to such books of tactics and of strategy as were within easy reach. I had especially been led to read military history with critical care and had carried away many valuable ideas from that most useful means of military education. I had, therefore, some notion of the work before us, and could approach its problems with less loss of time, at least, than if I had been totally ignorant.

My commission as brigadier general in the Ohio quota in national service was dated the 23rd of April . . .

To my great delight, I was able to obtain a fairly large collection of Civil War books and newspapers at an auction which were printed during the war, and shortly thereafter. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, The Century War Book, is written in segments from officers on both sides of the war. The excerpts and pictures included in this post were taken from this book, one of many that I purchased from this dream auction. Future posts will be taken from this book giving two sides to events which took place, and the officer’s perspective of the war from their side.

Thank you so much, for all you do, Monica! Another great history lesson!