Lincoln and Russia Part 1

Lincoln Criticizes Russian Despotism before the Civil War

Thomas Jefferson feared that it would only be a matter of time before the American system of government degenerated into a form of “elective despotism.”

“Timid men prefer the calm of despotism to the tempestuous sea of Liberty.”

~Thomas Jefferson

The relationship between Lincoln and Russia is a lesser-known aspect of the Lincoln era. This story is relevant today to provide insight into both historical and contemporary issues, as well as due to recent research in Russian archives that has revealed Russia's genuine reasons for aligning with the United States during the Civil War, which were not disclosed to Lincoln.

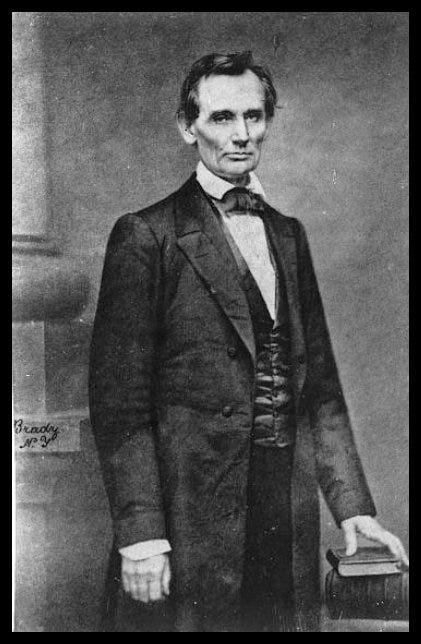

In this first part of Lincoln’s relationship with Russia during the Civil War, we need to go back in time when Lincoln was still practicing law in Springfield, Illinois, and examine his position on Russia as the despot of all nations.

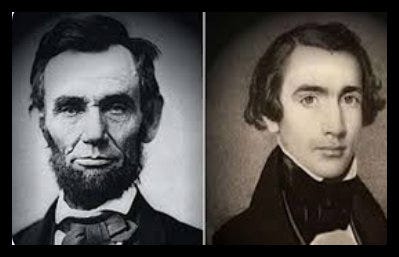

Lincoln corresponded with Joshua Fry Speed for many years. They originally met on April 15, 1837. when young, lanky Lincoln rode into Springfield, Illinois, with nothing more than his saddlebags. Inquiring at the general store about lodging, Speed, a coproprietor (who knew him by reputation), offered to share his bed with Lincoln. In the few minutes it took to climb the stairs and drop his bags, Lincoln had made a new home and a lifelong friend. During 1837-41, Lincoln’s friendship with Joshua Speed flourished. Speed introduced his socially awkward friend to Ninian and Elizabeth (Todd) Edwards—in whose home he met his future wife, Mary Todd of Lexington. Their most intense period of friendship culminated in the few weeks they spent together at Farmington in 1841.

Part 1 also introduces Edouard de Stoeckl, Russian Chargé de’ Affaires, who was the Russian Minister to the United States at the time of the Civil War. While not directly involved in the war's diplomatic efforts, Stoeckl was in Washington during the Civil War, representing Russia's interests.

On May 30, 1854, President Franklin Pierce, the 16th President of the United States signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which was designed to solve the issue of expanding slavery into the territories. This turmoil in Kansas became known as “Bleeding Kansas” and contributed to the growing tensions between the North and South that eventually led to the American Civil War. Pierce’s lack of leadership and his tendency to give in to pressure groups hampered his effectiveness in the foreign arena.

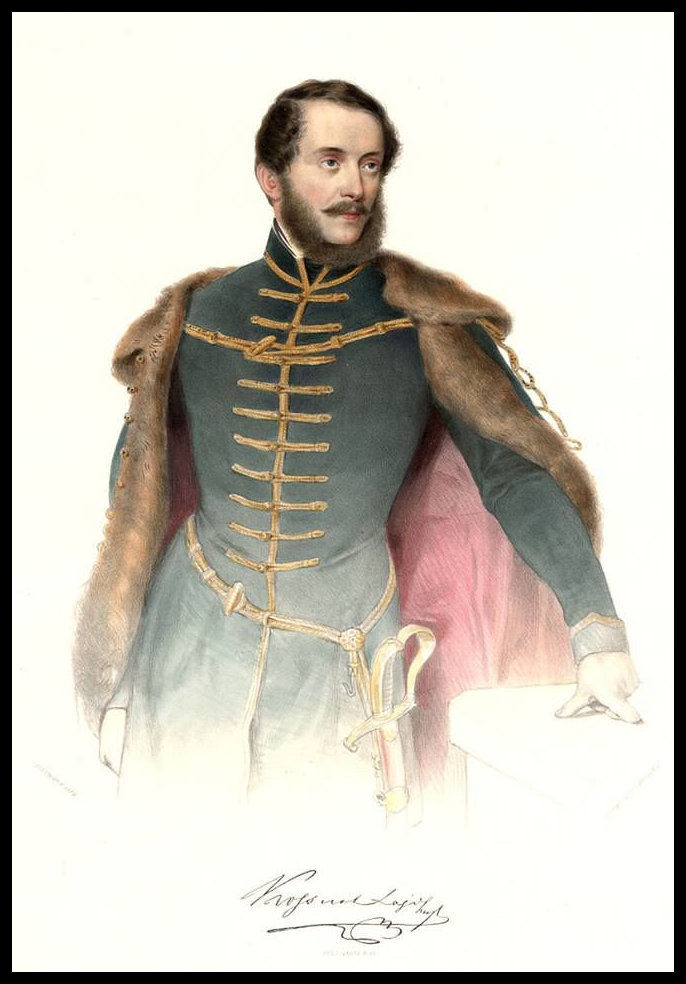

The Western powers urged the sultan to deny Austria's and Russia’s request for Lajos Kossuth’s extradition, resulting in him spending two years interned in Kütahya, Anatolia. The United States government invited Kossuth to visit America and sent a frigate (a small fast warship). He stopped in England, where he addressed mass meetings in English, learned from the Bible and Shakespeare during his confinement. Despite popular support in both the United States and England, he could not secure official backing for Hungary’s cause.

On the evening of January 8, 1852, Abraham Lincoln left his law office in Springfield, Illinois, and walked briskly to the courthouse on the square. A meeting—a result of the “Kossuth craze” which was sweeping the Northern States, was about to take place there and he had been invited to address the gathering. It was to be a demonstration on behalf of Hungarian freedom and protest Russia’s unwarranted intervention in Hungary’s struggle to throw off the yoke of Austrian tyranny.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, some four thousand miles distant from Springfield, political convulsions were shaking Europe civilization to its very foundations. The dark year of 1848 had seen the barricades and battalions of revolution rise from Paris to Moscow and from Prussia in the north to Sicily in the south. A democratic revolution had broken out in France in February of that year. Soon men throughout Europe rose up in arms for liberty—for economic security and better standards of living. Even in England there was unrest in the shape of the Chartist movement. This spree of liberty was the year when tow clashing ideologies represented by France, liberal and republican, and Russia reactionary and monarchial, were creating divided counsels and conflicting prophets, and keeping all Europe in a ferment. It was the year of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto; the year when Czar Nicholas of Russia wrote to Victoria of England, “What remains standing in Europe?”

Awakened Hungary under the leadership of Lajos Kossuth had succeeded temporarily in winning her independence from the Austrian overlords. The only resource left to the thoroughly beaten Hapsburgs was to invite the willing intervention of Russia.

Like a tempest from the north, the huge armies of Czar Nicholas I swept down on the little land of the Danube. To the fighters behind the barricades, the emperor issued a manifesto which closed with the words from Isaiah, “Listen, ye heathen, and submit, for us is God!” Kossuth’s followers fought heroically against hopeless odds, but after a brief resistance they were utterly crushed. Gloatingly, the Russian general reported to the Czar, “Hungary is lying at Your Majesty’s feet.”

By the hundreds of thousands, homeless, landless and property-less peasants and laborers, whose hopes of winning oft-promised rights and reforms had been shattered, now turned their faces towards America. Soon tidal waves of hungry, discontented people began pouring across the Atlantic bringing with them harrowing accounts of the plight of their countrymen who could not escape.

The United States showed profound empathy towards Europe's victims of oppression. This compassion was expressed through various actions, including public demonstrations advocating for Hungarian independence. One such meeting had already taken place in Springfield, on September 6, 1849. Judge David Davis, who presided over the Eighth Judicial Circuit, appointed Lincoln, his frequent traveling companion, together with five other citizens of Springfield, to draft appropriate resolutions to be sent to the American Secretary of State. As spokesman for the committee, Lincoln submitted a group of resolutions which, after expressing admiration for the Hungarians “in their present glorious struggle for liberty,” urged the United States government to “acknowledge the independence of Hungary as a nation of freemen at the very earliest moment.” This acknowledgement, as stated in the resolutions, is owed by American citizens to their Hungarian counterparts who are striving for republican liberty. It respects the legitimate rights of the government that the Hungarians are opposing.

Now, more than two years later, another public demonstration on behalf of Hungarian freedom was being held in Lincoln’s hometown. Governor Kossuth, exiled leader of Hungary’s revolt, was touring the United States, pleading the cause of his oppressed people. In Washington, Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln’s illustrious fellow-townsman, had been eloquent in his advocacy of an official governmental welcome to Kossuth. Dramatically, the Little Giant from Illinois had asked: “Shall it be that democratic America is not to be permitted to grant a hearty welcome to an exile who has become the representative of liberal principals throughout the world lest despotic Austria and Russia shall be offended?” And he answered, “The armed intervention of Russia to deprive Hungary of her constitutional rights, was such a violation of the laws of nations as authorized…the United States to interfere and prevent the consummation of the deed.”

Lincoln, having turned his focus to practicing law, eagerly joined public protests against tyranny, and spoke for human freedom. Despite Hungary and Russia being distant, they symbolized important concepts for him as a free American. Russia exemplified oppressive despotism, while Hungary represented the struggle for freedom. Lincoln's hatred of slavery led him to naturally sympathize with the oppressed.

The meeting drew a large crowd at the courthouse, led by John Calhoun. He discussed Hungary's fight against Austrian oppression, supported by Russian forces. Judge Lyman Trumbull and others recounted Kossuth's escape to Turkey, his imprisonment by Austria's influence, his release thanks to the United States, and the enthusiastic reception he received in America. After all the speeches, the presiding officer appointed a committee composed of Lincoln, Judge Trumbull, Archibald Williams, William I. Ferguson, Anson G. Henry, Samuel S. Marshall and Ebenezer Peck to draft resolutions implementing the sentiments expressed at the gathering. The next evening Lincoln presented these resolutions:

“Whereas, in the opinion of this meeting, the arrival of Kossuth in our country, in connection with the recent events in Hungary, and with the appeal he is now making in behalf of his country, presents an occasion upon which we, the American people, cannot remain silent, without justifying an interference against our continued devotion to the principles of our free institutions, therefore:

Resolve (1) That it is the right of any people, sufficiently numerous for national independence, to throw off, to revolutionize, their existing form of government, and to establish such other in its stead as they may choose.”

What strange words to be coming from the mouth of the man whom destiny was preparing to wage America’s great Civil War against secession! And yet this was the second time within three years that Lincoln expressed his belief in the right of secession. In 1848, in a speech in Congress, he had declared:

“Any people anywhere, being inclined and having the power, have the right to rise up and shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better. That is a most valuable, a most sacred right—a right which we hope and believe is to liberate the world.

Nor is the right confined to cases in which the whole people of an existing government may choose to exercise it. Any portion of such people that can, may revolutionize and make their own so much of the territory as they inhabit.

This is what Lincoln believed in 1848 and as late as 1852. But in 1860 he would no longer hold to that belief, although the South did. But to get back to the resolutions he helped prepare in January 1852:

2. That is the duty of our government to neither foment, nor assist, such revolutions in other governments.

3. That, as we may not legally or warrantably interfere abroad to aid, so no other government may interfere abroad, to suppress such revolutions; and that we should at once announce to the world our determination to insist upon this mutuality of non-intervention, as a sacred principle of international law.

4. That the late interference of Russia in the Hungarian struggle was, in our opinion, such illegal and unwarrantable interference.

5. That to have resisted Russia in that case, or to resist any power in a like case, would be no violation of our own cherished principles of nonintervention, but, on the contrary, would be ever meritorious, in us, or any independent nation.

6. That whether we will, in fact, interfere with such case, is purely a question of policy, to be decided when the exigencies arise.

7. That we recognize in Governor Kossuth of Hungry, the most worthy and distinguished representative of the cause of civil and religious liberty on the continent of Europe. A cause for which he and his nation struggled until they were overwhelmed by the armed intervention of a foreign despot, in violation of the more sacred principles of the laws of nature and of nations—principles held dear by the friends of freedom everywhere and more especially by the people of the United States.

The audience was in unanimous support of the points covered by the resolutions. “But what about Ireland?” asked Mr. McConnell. If the resolutions would add an expression of sympathy with Ireland’s struggle against Great Britian, and with all other people who were fighting for liberty, he could wholeheartedly support the entire series. Lincoln’s committee saw no objection to doing this and so added two more resolutions:

8. That the sympathies of this country, and the benefits of its position, should be exerted in favor of the people of every nation struggling to be free; and whilst we meet to do honor to Kossuth and Hungry, we should not fail to pour out the tribute of our praise and approbation to the patriotic efforts of the Irish, the Germans and the French, who have unsuccessfully fought to establish in their several governments the supremacy of the people.

9. There is nothing in the past history of the British government, or in its present expressed policy, to encourage the belief that she will aid, in any manner, in the delivery of continental Europe from the rope of despotism; and that her treatment of Ireland, of O’Brien, Mitchell and other worthy patriots, forces the conclusion that she will join her efforts to the despots of Europe in suppressing every effort of the people to establish free governments, based upon principles of true religious and civil liberty.

By establishing relationships with the Hungarian Kossuth and the Irish and German patriots, Lincoln positioned himself as a liberal, which would benefit his future political campaigns.

Kossuth's visit to the United States unexpectedly spurred the growth of the American or Know-Nothing Party. Kossuth's visit highlighted the influx of immigrants entering the country. The concerns, rivalries, and prejudices associated with nativism became prominent during this period. The Know-Nothings constituted a secret fraternity whose cry was “America for Americans.” The Party received its nickname from “I don’t know,” the ever-repeated reply of its members to questions about its purposes and activities. They denounced the alien liberalism of Kossuth, Garibaldi and Mazzini and the tendency to push democracy to extremes. They thundered that the “radical” ideas propagated by “German infidels and Italian patriots” threatened to undermine American institutions. So, they admonished, “Put none but Americans on guard,” and proceeded to oppose politically all who were not native-born white, Protestant Americans. The Know-Nothings grew rapidly in membership and influence and soon became a political power of great importance throughout this country.

Know-Nothings zealots called on Lincoln in Springfield to join them in their antiforeign and anti-Catholic campaign. It was the expedient thing for politicians to do. With unfeigned disgust Lincoln gave his reply: “Who are the native Americans? Do they not wear the breechclout and carry the tomahawk? We pushed them from their homes and now turn on others not fortunate enough to come over so early as we or our forefathers.”

It was while denouncing the bigotry of the Know-Nothings that Lincoln found once again denounced Russia as the world’s leading exemplar of despotism. In a letter to his friend Joshua Speed written on August 24, 1855, he declared:

“I am not a Know-Nothing; that is certain. How could I be? How can anyone who abhors the oppression of Negroes be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “All men created equal, except Negroes.” When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read, “all men are created equal, except Negroes and foreigners and Catholics.” When it comes to this, I shall prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.”

Lincoln made this reference to Russia as the outstanding example of despotism and repression at a time when the United States and Russia were the warmest of international friends. Notwithstanding the fact that Russia was then the stronghold of reaction and the most hated and despised nation in Europe, and that democratic America was openly and proudly proclaiming her friendship for the realm of the Czars.

During the first half of the nineteenth century Russia, like the United States, was constantly at odds with Great Britian, and as the years progressed the clash of European imperialisms made war between Great Britain and Russia inevitable. The Crimean War broke out in 1853, nominally over a monkish issue between Russia and Turkey involving the guardianship of certain holy places in Jerusalem and the insistence of the Czar in exercising protection over the Greek Orthodox subjects of the Sultan. This quarrel proved a fortunate occasion for the French and British to draw the sword against the Czar. It was to develop into an epic struggle between the Lion and the Bear for the control of the route to India. The squadrons of the allies entered the Black Sea and bottled up the Russian fleet, laying siege to the heavily fortified city of Sebastopol, Russia’s mighty arsenal in the Crimea and the military center from which she threatened the south.

Ties of blood and a common language and a common history should have made the United States rabidly pro-British in this war of imperialism. “England is our friend when the question is against Russia; for who does not see that Russia represents that spirit of life and government which is diametrically opposed to our own.” This opinion expressed by Harper’s Magazine was the feeling of many Americans. But the United States had become England’s bitterest maritime rival. Decades of bickering over rights of neutrals and clashing commercial interests now had come to the forefront to throw official American sympathy violently on the side of Russia as another great victim of British imperialism.

Baron Edouard de Stoeckl, Russian Chargé de’ Affaires at Washington, observed with pleasure the jealousy and bitterness existing between the governments of Great Britain and the United States as they quarreled constantly over commercial rivalries. Stoeckl tried hard to drag America into the Crimean War as an ally of St, Petersburg. “Russia,” he wrote, “must be ever watchful, must never lose an opportunity to fan the flames of hatred.” He played upon the bitter rivalries of the two English-speaking nations. In disregard of American neutrality, he proposed plans to engage American privateers to prey upon the British commerce. He prevailed upon his government “to encourage the Yankees to trade with her, to offer them special inducements in the way of lower tariffs, especially on cotton and colonial goods which have until now been brought in English bottoms.” He wrote, “The Americans will go after anything that has enough money in it. They have the ships, they have the men, and they have the daring spirit. The blockading fleet will think twice before firing on the Stars and Stripes. When America was weak, she refused to submit to England, and now that she is strong, she is much less likely to do so.”

It was not Stoeckl’s fault that the United States did not become an active belligerent in the Crimean War. His propaganda in Washington proved highly effective. The Russian Legation was flooded with requests for letters of marque from American citizens desiring to enter the service of the Czar. From Kentucky came the offer of three hundred riflemen who volunteered to go to Sebastopol to fight the British.

President Pierce rather expected a rupture with England over neutral rights. Complaining of British tactics, he said, “We desire most sincerely to remain neutral, but God alone knows whether it is possible.” Secretary of State Marcy added bombastically that the United States would defend to the utmost her right as a neutral to carry on legitimate commerce, and that she would not recognize a paper blockade. He announced that orders were being dispatched to the American squadron then on its way to Japan to proceed instead to the Baltic to defend the United States shipping.

In the spring of 1855, Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War in the Cabinet of President Pierce, sent a commission of three American army officers to Russia and other lands of Europe to study the organization of European armies and to observe the war in Crimea. Among the observers was Captain George B. McClellan, then only twenty-eight years old and looking even younger than his years. In France, the American officers were presented to Napoleon III and the Empress Eugenie. They were royally entertained in Russia but were refused permission to visit the battlefront. Notwithstanding this refusal, Captain McClellan and his associates journeyed to Sebastopol where they studied the military developments firsthand.

American friendship for Russia was evident during the Crimean War. Great Britain avoided conflict with the United States to prevent American maritime power from aiding Russia, yielding on issues involving the blockade and promising strict conduct regarding neutrals. America’s insistence that England accept the principle that the flag protects the cargo greatly benefited Russian commerce. Fear of American power influenced the allies’ rejection of Spanish help against the Czar. Some Russians believed that if England had not backed down in disputes with the United States, America might have allied with Muscovy.

During the friendly exchange between Washington and St. Petersburg, Secretary Marcy made it a point to ascertain how Russia would view annexation of the Sandwich Islands by the United States—a move which both England and France strongly opposed. Stoeckl, the Czar’s Foreign Minister advised Marcy that anything which would antagonize her enemies would meet with Russia’s approval.

So, a few months after receiving this friendly assurance, Marcy imparted to Stoeckl some highly important secret information that had fallen into his hands. The United States government had learned from sources regarded as reliable, Marcy disclosed, that England was planning to attack and seize Alaska. Acting on this information Stoeckl warned the Governor of Alaska to prepare for eventualities. Officers of the Russian-American Company, fearful that they were in no position to defend Alaska against a British raid, made a frantic effort to ensure the safety of their possessions by the ruse of a fictitious sale to an American company. They thus hoped that Alaska could be claimed to be American rather than Russian territory, in the event of its falling into the hands of the British. The United States government refused to be a party to such a plot, and the plan of a pretended sale was abandoned.

But the United States undertook to display her good will in another manner. Recalling that Russia had proposed to act as mediator in the War of 1812, Marcy now offered the tender of a similar service by our government in the Crimean War. The President, with the approval of the Cabinet, stood ready to act as a mediator, he advised Stoeckl. The Secretary of State was working on a plan to be submitted to the belligerents whereby the bloody struggle could be brought to a speedy end. The Russian government neither accepted nor rejected America’s offer. Her Chancellor professed his faith in the impartiality of the United States, but he doubted whether the enemy would agree. Baron de Stoeckl expressed the belief that England would surely reject Marcy’s proposal because of “America’s well-known partiality for Russia.” To which Marcy replied, “Let her do so. It will be one more count against her in our eyes. You surely cannot object to that.” As in the case of Russia’s offer to mediate the War of 1812, so now American’s proposal to act as mediator in the Crimean War likewise fell through.

Throughout the war Marcy repeated expressed his friendship with the Czar, while on numerous occasions Czar Nicholas I, and later his son Czar Alexander II, who succeeded to the throne when his father died in March 1855, sent thanks to President Pierce and Secretary Marcy for their kindly deed and encouraging words on behalf of Russia.

As the allied operations against the great Sebastopol arsenal in the Crimea stretched out for almost a year, the ultimate defeat of Russia became more and more apparent, one European nation after another abandoned the ranks of neutrals and joined the enemies of the Czar. By the time the beleaguered Black Sea port finally fell into the hands of the allied conquerors, the United States was the only major government int the world that was neither ashamed nor afraid to acknowledge her friendship for the Muscovite Empire.

But back in Springfield, Abraham Lincoln remained altogether unmoved by the pro-Russian propaganda with which the Czar’s legation in Washington had flooded the land. Nor was he influenced by the gestures of mutual admiration which heads of the two governments exchanged. He remembered Russia only as the “foreign despot” who “in violation of the most sacred principles of the laws of nature and of nations—principles held dear by the friends of freedom everywhere and more especially by the people of the United States…” had, through unwarranted and armed intervention, overwhelmed little Hungary as she strove to throw off the yoke of Austrian tyranny. So, when in August 1855 Lincoln desired to illustrate to Joshua Speed what happens when bigotry, reaction and suppression overwhelm a land, he instinctively pointed to “Russia…where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.”

Lincoln was still a stranger to the mysteries of world politics which made America so violently pro-Russian during the Crimean War. Idealist that he was, he still did not realize that altruistic friendship is a thing almost unknown among nations; that their relations toward each other are not necessarily determined by sentiment or gratitude, but first and foremost by self-interest; that the absence or presence of conflicting interests or common animosities, fears, hatreds or enemies have been constructed. Nearly six years were still to come and go before Lincoln would be suddenly catapulted into the colossal responsibility of saving the Union from breaking into pieces and managing the nation’s delicate affairs while the United State trembled on the very brink of a foreign war. Then, irony of ironies, in these soul-stirring days, democratic America would be able to count on only one friend among the entire family of nations—democracy-hating, despotic Russia, where, as Lincoln so aptly phrased it, “they make no pretense of loving liberty.”

*Since this series about Lincoln and the Russians will consist of several parts, references will be posted at the end.

Well done.

Exceptional narrative that exposes so many intricacies. You may be interested in Will Zillow and his writings on Prussia. Anyway, thank you for this.