“It is painful enough to discover with what unconcern they speak of war and threaten it. They do not know its horrors. I have seen enough of it to make me look upon it as the sum of all evils.” ~ Stonewall Jackson

The outbreak of hostilities between the North and South deeply affected Edouard de Stoeckl. He had intimate friends in both sections of the United States. It grieved him as he wrote to Prince Gorchakov shortly after the fall of Fort Sumter:

“To see the two sections of the country, called by nature herself into the most intimate alliance, engaging in a war without rhyme or reason and without any other possible termination that mutual ruin and destruction. Eighty years of prosperity without equal in history are due to the Union. It has been broken in the name of an abstract principle and converted into mutual hate and hostility. It appears that in all human nature there lurks a lust for blood that must be satisfied from time to time.”

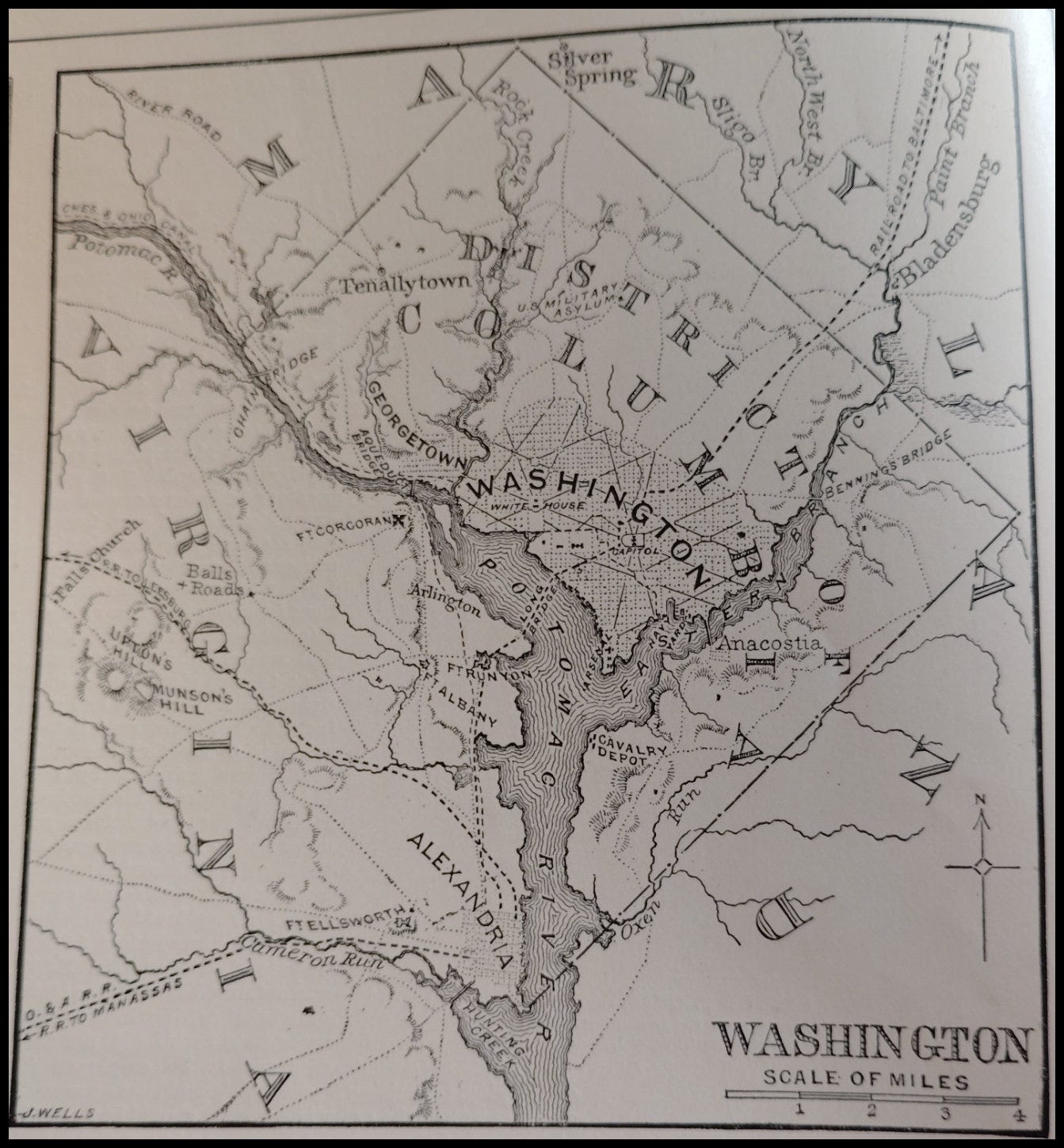

Within a few days, Stoeckl was advising his Russian government: “Washington is in a state of blockade. Mail is interrupted, telegraph wires cut, railroads out of commission by the partial destruction of the roads or of several bridges. For eight days we have received no mail or newspapers.

Confusion reigns supreme. Men by the thousands are leaving their shops, stores or professions and volunteering for military duty. Massachusetts troops have arrived in Washington. More than 20,000 militia will soon be concentrated in the National Capital.”

Stoeckl also pointed out that Lincoln’s proclamation for 74,000 men, though successful in raising troops for the federal army, served also to consolidate the South. “The legislature of Virginia has declared for secession. Maryland mobs attacked United States troops as they passed through Baltimore.” The Russian Minister predicted that Maryland, too, would soon secede. More officers were resigning their commissions in the federal army and navy and joining the Confederates. Most noteworthy were Colonels Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston. Few if any experienced military leaders were left in the federal forces.

With a single stroke of his pen, Lincoln divided the Union into two hostile camps without hope of reconciliation. The border states, once mediators between the North and South, had been forced out of the Union. Although the proclamation aimed to defend the Capital, it led to Virginia and Maryland seceding, placing the Capital in enemy territory. The White House, close to Virginia across the Potomac River, faced rumor of an imminent Southern attack. A hundred men guarded it, while the federal treasury was fortified and the Capital turned into barracks. Stoeckl suggested abandoning the Capital and destroying its buildings to prevent enemy capture or forcibly seizing Maryland and Virginia and governing them as conquered provinces—an unusual approach for a republic.

Cassius M. Clay, the Kentucky abolitionist who stumped his States for Lincoln as a reward was to be appointed Minister to Russia, delayed his journey to St. Petersburg to organize and captain a volunteer White House guard. He expected the war to come momentarily to Washington and armed himself with three pistols and an “Arkansas toothpick,” he was prepared for a last-ditch battle at the doors of the Executive Mansion.

The danger and predicament in which the nation’s Capital found itself, Stoeckl believed, was due to Lincoln’s “gross inexperience in the management of the more important affairs of state as well as of military affairs. He wrote, “Several thousand troops are stationed here, and no measures have been adopted to provision them. Washington obtains its provisions from Virgina and Maryland…Indignation is so great in Baltimore that any relations with Washington are regarded as high treason.”

Stoeckl also reported that the federal government, realizing its inability to hold the arsenals at Harpers Ferry and Norfolk, Virginia, had ordered the buildings burned and the supply of arms and ammunition destroyed. “The value of the destroyed property at Norfolk naval arsenal is estimated at $27,000,000. Several fine naval vessels which were not quite ready to take the sea have burned and sunk.”

Lincoln faced additional challenges from a contentious Cabinet with conflicting opinions. The Russian Minister noted that the President was heavily influenced by Blair, the Attorney General, and his father, both fervent abolitionists pushing extreme views on slavery. Lincoln's policies alienated border States, leading to the resignation of their military and naval personnel, who offered their services to Jefferson Davis.

In the meantime, Jefferson Davis is organizing a 50,000-strong army, potentially doubling it if needed. In response to Lincoln's call for 75,000 men, he urged shipowners to arm themselves as privateers against Northern merchant ships. Davis is widely supported by the Southern people, who trust his well-considered policies. The rumors of a large Confederate army advancing from Baltimore to attack Washington, as well as Confederate gunboats sailing up the Potomac to bombard the capital, proved unfounded, much to the relief of Washington residents. With this newfound sense of security, the populace began to advocate for military action against the Southern states in order to compel their return to the Union.

Stoeckl pointed out to St. Petersburg, that Lincoln had plenty of troops, however, they first had to be trained and properly equipped for a war of invasion. Lincoln deluded himself that a conquest of the South—even if he should achieve it—will succeed in re-establishing the Union. He should have known that by invading the South during the months of June and July, he would be risking the destruction of his armies because of the terrible heat of the South. Since he was entirely under the influence of the demagogues of his Party and cannot do otherwise than to obey them, these violent men were masters of the situation and took advantage of the enthusiasm displayed by the general public of the North by agitating their own radical doctrines.

Under the direction of committees, daily deputations were sent to the President to dictate the course of action he should follow. Senator Wilson, noted for his radical views, arrived with a group of extremists and called upon Lincoln, “We saved you from an attack by the secessionists. But you are not threatened by an even greater danger—one from the North. One backward step or even one false step will result in your downfall.”

The principal newspapers in the larger cities became the mouthpiece of the extremists. Their fanaticism spared neither Lincoln nor his Cabinet. They no longer demanded conquest alone, but also the extermination of the Southern States. One of these newspapers declared: “The people will not wait. They will not hesitate to choose a new leader should Lincon fail them.” The widespread distribution of propaganda by the press resulted in significant public unrest. Incidents have already occurred in major cities. In New York, groups were marching through the streets and participating in various acts of violence. Residents organized and armed themselves to protect their personal safety and property.

From the Russian Embassy in Washington, Stoeckl watched developments and reported in detail to St. Petersburg. On May 13th he informed Prince Gorchakov:

“More than 50,000 troops are in Washington and Maryland. These contingents are composed of militias who have enlisted for only three months. They will be replaced by 64,000 enlisted volunteers as soon as their training is completed.

A campaign was to have been launched on the third of this month. It is proposed that Virginia be invaded at three points: at Norfolk near the coast, at Alexandria located seven miles from Washington on the right bank of the Potomac, and at Harpers Ferry on the west. From these three points the federal troops are to advance towards Richmond, the Capital of Virginia, and take possession of the State. But up to this moment no movement has taken place, and the army is in the same position that it was one week ago.

This delay is due to the disturbing news now received from the West. Tennessee declared it has seceded from the Union; Kentucky is still undecided, but everything appears to indicate that she will follow the example of Tennessee. These two States could furnish, in the case of need, 80,000 men who are accustomed to the privations of Western life and who, when it comes to handling firearms, have no equals in the Union.

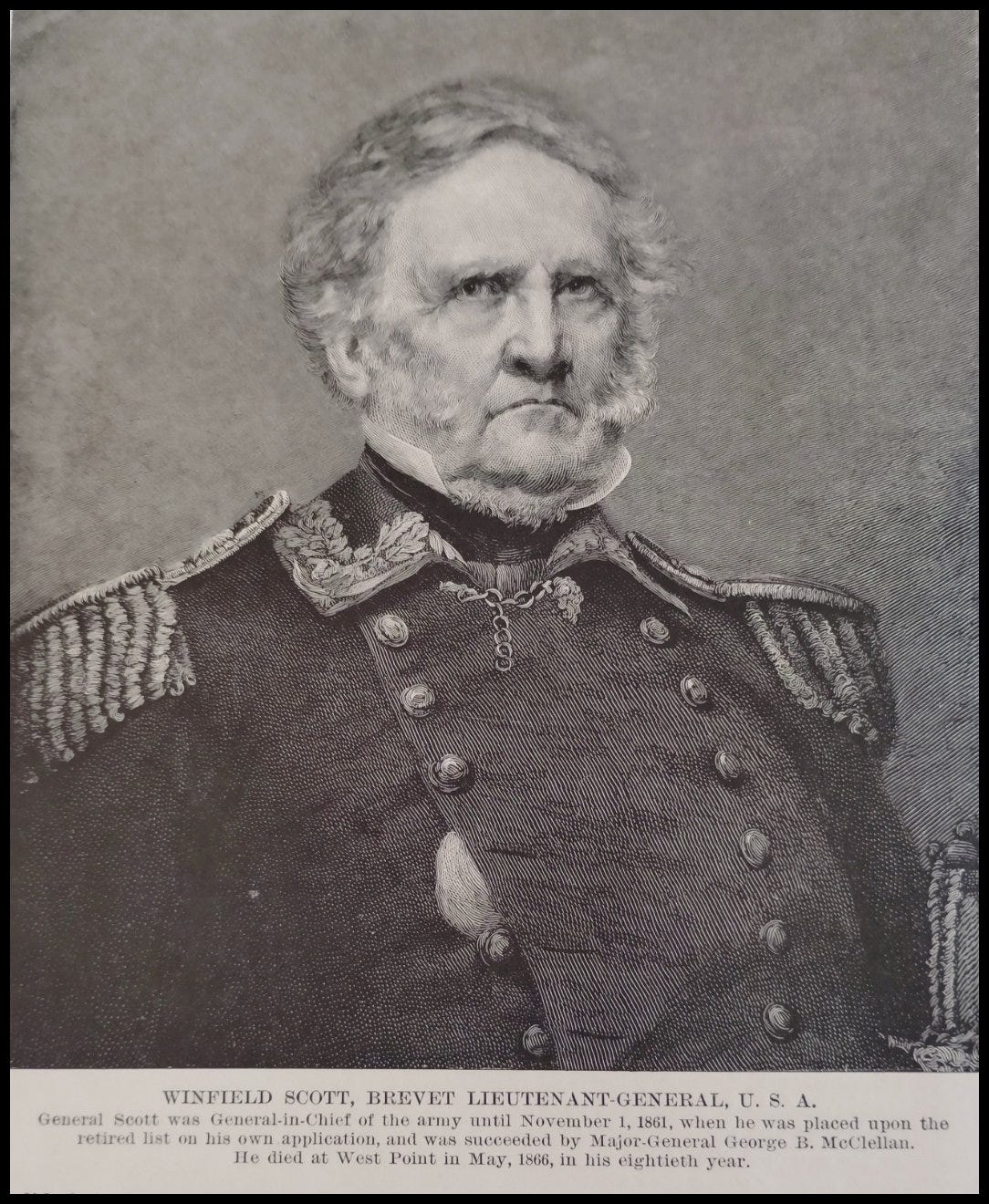

General Scott, who commands military operations, hesitates to enter upon a war of invasion with an army composed of untrained and badly organized militias. These troops have neither wagons nor field hospitals; they lack the most rudimentary needs of an army…There are no commissaries. The regiments which arrived here procured provisions as best as they could and paid for them in gold. At New York and Philadelphia and also here in Washington, several regiments have been lodged in hotels where each soldier is costing the public treasury one to two dollars a day.

In the South preparations are being made for a desperate resistance of the Northern invasion, but we know absolutely nothing of the campaign plans of Jefferson Davis. It is on this point that the government at Montgomery has an immense advantage over the Washington government whose every strategic movement is immediately known and often publicized in advance by the press.

There is a great divergence of opinion between Mr. Lincoln and General Scott. The former is subject to the pressure of the Northern States, which, as the price of their sacrifices, demand that the government act without delay. Mr. Lincoln cannot escape the exigencies of public opinion; he must act, no matter what the risk. General Scott sees the question only from the military standpoint and refused to undertake an expedition without reasonable assurance in advance of success. As to the members of the Cabinet, some share the President’s opinion, others General Scott’s; and the result of this discord will be the adoption of half measures which will serve only to increase the administration’s predicament.”

Stoeckl pointed out that Lincoln’s and Seward’s declarations that the United States is one nation inseparable and indivisible, though correct in theory, was altogether false in fact. The Union had not ceased to exist. The United States is one and will continue to remain one single nation. In theory this view is incontestable. Unfortunately, Seward was mistaken when he said the “United States is one nation.” Since the inception of the federal government, the North and South have shown distinct differences. Influenced by various local institutions and possibly diverse climatic conditions, two populations have developed unique identities. Over the years, the federal pact increasingly appeared to be an artificial bond between two sections with inherent differences. The issue of slavery was a significant factor, but it was only one of several factors. The division of the Union was the result of long-standing national differences, and the conflict that emerged was fundamentally one of principles. The government's position was a complex one. On one hand, it involved protecting the integrity of the principle of supreme authority; on the other, it required responding to the demands imposed by current circumstances. Ultimately, a compromise could have been necessitated, but the government's proficiency was demonstrated by its inability to act at the appropriate time. It failed to recognize its true function and, instead, it succumbed to the influence of extremists, attempting to conquer and subjugate the South, which could have inadvertently led to the destruction of the Union and erode the foundational principles on which it was established.

The Russian Minister voiced his low opinion of Lincoln’s capabilities, whom he regarded as “President only in name.” He believed Lincoln was completely under the domination of the extremists who surrounded him and controlled the government:

“The more complicated the situation becomes, the more feeble and undecided he (Lincoln) appears. He admits that his task is beyond his powers. Fatigue and anxiety have broken him down morally and physically.

As for Mr. Seward, his services in the office of Secretary of States hardly justify the high reputation he formerly enjoyed. He is completely ignorant of international affairs. At the same time his vanity is so great that he will not listen to anyone’s advice. His arrogance harms the administration more than does the mediocrity of his colleagues.

Having determined Lincoln and his chief Cabinet officer as mediocracies and failures, Stoeckl reported this to his government:

“Mr. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury, is the only one who possesses real ability. A confirmed abolitionist, he has been consistently opposed to making concessions or offering compromises to the South. But he does advocate the use of force as a means of restoring the Union.

Besides the official advisors of the President there are sinister influences which unfortunately exercise great power over the vacillating Chief Executive. Mr. Greeley and Mr. Blair, experts in the art of partisan intrigues and scheming, are at the head of a secret coalition of Senators and Members of the House of Representatives. Mr. Greeley is in New York where he influences public opinion through the medium of the press. Mr. Blair is here and acts directly upon the President.

This group imposes pressure upon the President to use extreme measures, and hostilities would have started already were it not for the opposition of General Scott who has said again and again to the President that launching an invasion without an army composed of raw recruits badly trained and without proper equipment would result in certain defeat. In consequence, General Scott has been violently attacked by Greeley and Blair. He would have already been replaced were it not for the difficulty of finding a commander who would consent to obey their dictates more or less blindly.”

Not long after, Stoeckl learned that “the federal government has given up the plan of launching an invasion of the South…General Scott has succeeded in demonstrating the dangers of such a move. He has prevailed in his proposal of occupying strategic points in Virgina and Missouri and waiting in this position until autumn, and then to advance into the South if necessary. It is hoped that in the interim, the Confederate States, surrounded on land among their entire borders and blocked by sea, will be forced into submission.”

On July 3, 1861, the day before Congress assembled for its extraordinary session, while Lincoln was putting the finishing touches on his message, Stoeckl wrote to Prince Gorchakov:

“I have had the opportunity of talking with several leaders. If I can judge from their comments, they have decided to adopt the most violent measures and to undertake a war to the bitter end, and to denounce as traitors all who dare to speak of compromise. As happens in all political convulsions men of peace and moderation are howled down, and events are directed by a noisy minority who resort to extremes.

The administration itself will not exercise much leadership. The extremists of the Republican Party have not forgotten that the President has been inclined to negotiate with the Confederates. They are trying to maneuver him as to prevent him from attempting such a step. But the scheming in Congress will be directed chiefly against the commanding general of the federal army. He is criticized for his inaction and failure to invade the South with the 200,000 men under his command. They do not dare to attack him openly because he is too popular throughout the country. But they endeavor to undermine him secretly.

General Scott has not been intimidated by these threats and continues to act with prudence and circumspection. Although he has an army of from 200,000 to 250,000 men, they are untrained. The stagnation of business and industry threw thousands of persons onto the streets who found relief only in the army. The large cities furnished the mass majority of these men. They are a strange conglomeration of all nationalities. Several regiments are composed entirely of Germans. Others contain only Irish. There are still others in which you will find Spaniards, Italians, Belgians and French. There are even a small number of Russians and Serbians. The generals are men who only yesterday were lawyers and merchants and are entirely ignorant even of the elementary principles of their new offices. Officers of the regiments are chosen by the soldiers, so how can they issue orders to men to whom they owe their positions and who have the right to dismiss them at will?

Some 50,000 to 60,000 troops are bivouacking in the environs of Washington. It is difficult to name a form of disorder or rowdyism they do not commit, and under the very eyes of the President and the high command. Is it any wonder then that General Scott hesitates to undertake an invasion with an army composed of such elements, particularly with the season of bad weather approaching? This able American army veteran does not underestimate his adversaries, who though not superior in organization or size have the advantage of fighting on their own soil and of being able to convert the fighting into guerrilla warfare. They have already started this form of attack. The outposts of the federal troops cannot venture beyond their lines without falling into some ambush of the Virginian guerrillas.

There is still another motive contributing to General Scott’s policy of moderation: it is his desire to avoid bloodshed as far as possible. He told me recently, “If the objective of this war is the reconstruction of the Union, if our enemies of today are again to become compatriots, it is unwise to antagonize them unduly.”

The President of the Confederacy has changed the seat of government to Richmond, Virginia, whence he directs military operations…Up to this point Jefferson Davis has completely justified the reputation he has always enjoyed of being a skillful and energetic leader. He has won the confidence of his people to the point of being able to assume dictatorial power. This not a small advantage which the South has on her adversaries of the Noth where everyone wishes to command and no one to obey.

Whereas the army of the North cost (and I have this from the Secretary of the Treasury himself) a million dollars a day. Mr. Davis, without resources other than a loan of $15,000,000, has succeeded in raising an army of an estimated 100,000 men who are fairly well armed and ardently resolved to defend every inch of their territory…

On July 4, 1861, the eighty-fifth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Congress assembled in a special session in pursuance to Lincoln’s call. From March 4th until July 4th, the momentous issues of the Civil War had been decided by Lincoln alone. By his own fiat he had suspended the writ of habeas corpus, first in a limited area and then generally all over the country. He had issued a proclamation of blockade in all the ports of the seceded States. He had declared martial law. By a proclamation he had ordered the regular army increased by 22,714 officers and men and the navy by 18,000 and had called for volunteers to serve for three years. Public money was spent without congressional appropriation. As a congressman, Lincoln had once bitterly denounced President Polk for his alleged usurpation of power in prosecuting the Mexican War. Now, Lincoln as President was going infinitely beyond Polk.

In the gallery of the House of Representatives, a clerk prepared the message of President Lincoln on this extremely hot day of July 4th. Lincoln reports what had been done to meet the emergency as asked for approval:

“This issue embraces more than the fate of the United States. It presents to the whole family of man the question whether a constitutional republic or democracy—a government of the people, by the same people—can or cannot retain its territorial integrity against its own domestic foes. It presents the question whether discontented individuals, too few in numbers to control administration according to organic law in any case, can always, upon the pretenses made in this case, or any other pretenses, or arbitrarily without any pretense, break up their government, and thus practically put an end to free government upon this earth. It forces us to ask: “Is there, in all republics, this inherent and fatal weakness? Must a government of necessity be too strong for the liberties od its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?”

Toward the end of the message Lincoln said: “This is essentially a people’s contest. On the side of the Union, it is a struggle for maintaining in the world that form and substance of government whose leading object is to elevate the condition of men—to lift artificial weights from all shoulders.” Lincoln then requested an appropriation of $400,000,000 to make the contest “short and decisive.”

The President was authorized to raise the army to 500,000 men, to borrow $200,000,000, and to issue $50,000,000 in treasury notes. Only four months earlier the country seemed to prefer disunion to war. But Lincoln, by his tactful and forceful measures, had resolved the issue; the rebellion must be crushed and the Union restored. His war policy received approval in the House with only five dissenting votes.

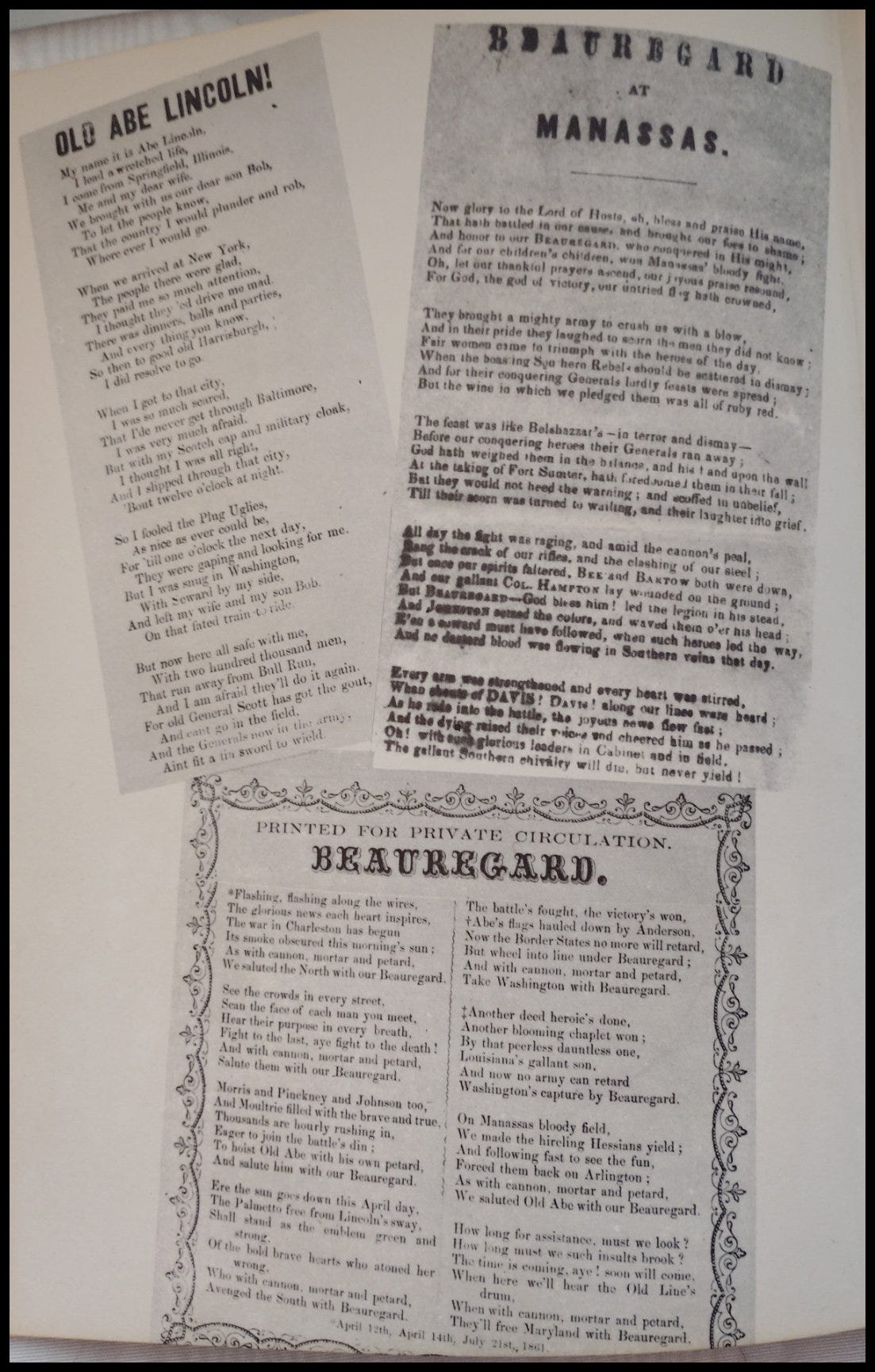

While Congress was voting approval of Lincoln’s conduct of the conflict and granting him men and money to crush the rebellion, a cry rang throughout the North, “On to Richmond!” As long as he could, General Scott had resisted the demand for immediate action. But the political pressure and the newspaper clamor became too powerful, and at last he gave in. Reluctantly he gave the order for an advance upon Richmond, the Confederate Capital.

General McDowell, in command of 35,000 men, was ordered to strike a Confederate force and drive the Southerners back from Manassas near a little stream called Bull Run. Another Union commander, General Patterson, was to advance up the Shenandoah Valley to prevent the Confederates there from going to the aid of their comrades at Manassas Junction. On July 16th, McDowell led his citizen soldiers across the bridges spanning the Potomac and began the long-awaited advance. By the 19th he was at the Bull Run stream behind the Confederates, led by General Beauregard.

Members of congress, confident of a victory and anxious to see the Confederate rebels receive a whipping they would never forget, took horses, or hired vehicles and accompanied by their ladies drove southward from Washington to watch the spectacle of real war across the Potomac. On the field of Bull Run, less than a day’s horseback ride southwest of Washington, the green federal army fought courageously for many hours. Lincoln waited anxiously in the White House for reports of the battle. The first accounts were regarded as favorable. But what should have been a victory turned into a horrible disaster chiefly because of the inexcusable failure of General Patterson, united his forces with those of Beauregard and attacked the green federal army, which crumpled up and was driven from the field. Panic-stricken, the raw recruits turned into a mere mob of individuals and fled in horror.

At about 4 o’clock…General Beauregard hurled 2,000 cavalrymen, who had not up to this time taken part in the action, against the federal army. The effect of this maneuver was instantaneous. All troops without exception took to their heels and soon the entire army was one mad stampede in the woods and on the highway. The officers of the militia were the first to take flight, and the soldiers ran after them, throwing their haversacks and rifles. It was then that the federal army returned to Washington only four days after taking it to the field.

The official government bulletin of July 21st concerning the disaster appeared to be carefully censored. It admitted Union casualties of only 50 killed and 200 wounded, whereas the Russian Minister who had been on the scene estimated the casualties at 5,000. Although the official bulletin stated that, “The enemy was superior in number.” The armies were almost equal in numerical strength. General McDowell had more than 60,000 men. The Southern army was composed of between 40,000 to 45,000 men but eventually re-enforced by 15,000 of General Johnston’s men.

Manassas Gap was the critical point and McDowell sent half of his forces there. But Patterson, instead of pursuing Johnston, retraced his steps and permitted him to go by forced marches to Manassas Gap, where he arrived with the rest of his troops the night before the battle. The brilliant maneuver of General Johnston, and the bungling retreat of General Patterson can be explained by the fact that the former is one of the most capable officers of the army, whereas the latter is a Philadelphia stockbroker. Patterson offered the excuse for his retreat that he had no means of transportation, and that he lacked provisions, and that his troops refused to advance. It is probably the truth, for with untrained volunteers and a commissary which was entirely disorganized, nothing was impossible. He was stripped of his command, but apparently, the army did not profit from their mistake as he was replaced by General Banks, a Boston Lawyer.

“The federal army’s losses have been enormous,” reported Stoeckl. Everything was abandoned: seventy cannons, thirty to forty thousand rifles, a considerable quantity of ammunition, wagons and medical supplies have fallen into the hands of the Southern army. The loss of men is terrific. The government published nothing on this subject, but from all the information that I have been able to obtain, the number killed, wounded, or captures, and deserters is at least 10,000 men.”

Continuing his report of the Battle of Bull Run to St. Petersburg, Stoeckl depicted the despair and confusion which enveloped the North after the disaster:

“A day after the battle, Washington offered a sad spectacle. Groups of soldiers, returned from the battlefield, exhausted and bedraggled, crowed in the streets and begged for food from door to door. A deadly fear pervaded the city that momentarily it might be invaded. Fortunately, a thousand regular troops performing police functions succeeded in leading the deserters into the camps near the Capital which they had occupied prior to the march on Virginia, and order was restored.

No one was more affected by this disaster than General Scott. He knew from experience the danger of sending untrained volunteers into combat and had resisted as long as he could. But, the pressure was too great, and he had to yield. When the news of the rout arrived, the President went to the residence of General Scott to ascertain what emergency measures were now necessary. “The first thing that you must do,” the veteran answered, “is to accept my resignation because I have committed one of the gravest offences possible, that of yielding to the clamor of the demagogues.” However, General Scott is the only one who has not lost his head. He has already started to recognize the army. But he has declared that he will require ample time before he will again be in a position to take the offensive.

Stoeckl’s estimate of 10,000 federal casualties proved to be far from accurate. The official figures was; killed, 460; wounded, 1,124; missing, 1,312, for a total of 2,896. Similar inaccuracies will be noted in his reports pertaining to other battles. Remarkably well informed as a rule, the Russian Minister, was reporting contemporaneously, frequently immediately after the event, and had to rely upon unofficial sources and hearsay for his information. Considering the dispatch with which he usually forwarded his quickly acquired information to St. Petersburg, it is surprising how accurate he proved to be in most instances.

While Washington trembled with fear that Generals Beauregard and Johnston were planning next to strike at the Capital, Lincoln sent out a call to thirty-four-year-old Major General George B. McClellan, in charge of military operations in Western Virginia, to hasten to Washington to replace McDowell in the Army of the Potomac and who’s task was to recognize the shattered army, and replenish the ranks with new regiments of volunteers.

As the days passed, the federal defeat was greater than anyone expected. Russell, the foreign correspondent for the London Times, witnessed the event and reported that, “I had not seen such a rout, not even among the Hindus or the Chinese. The Southern troops on the other hand fought extremely well.”

The financial situation became more serious than all other difficulties at this time. Congress had generously granted the President $500,000,000 instead of the $400,000,000 he had requested. But it is another story when it came to raise this exorbitant amount. An embarrassed Congress suggested a direct tax, but representatives of the people objected because of the unpopularity of such a tax. The big bankers of New York were in no position to lend the government more than forty to forty-five million dollars. Secretary of the Treasury, Chase had previously sent agents to Europe to float a loan, but its success was a failure. The recourse would have to be treasury bonds with the result that paper money will lose its value, and public credit would be ruined. The danger that the country faced, lied not so much in the lack of success in military operations, but in the intrigues and secret dealings of the radical parties and the weaknesses of the administration which, without sharing the views of the demagogues, who succumb to their evil influence and permits itself to be dragged blindly along to certain ruin.

By this time, the government forbid postmasters to carry newspapers in the mail which advocated conciliation and compromise. The newspapers who were opposed to was had to suspend publication. In towns the extremists stirred up the people and smashed the plants of the moderate newspapers. Conditions were such that a mere denunciation by a general is sufficient for a person to be arrested and imprisoned. The act of habeas corpus and all the personal guarantees which the Americans have appeared to prize so much, have vanished and had given away to martial law, which was being enforce throughout the North. During this period, our country was not far from a reign of terror that existed during the French Revolution, but what makes the resemblance more striking is that all these acts of oppression were made in the name of liberty.

If Beauregard had attempted to take Washington after Manassas in 1861, it is worth considering whether the Confederate army could have overtaken Washington and consequently ended the war. If they had taken Washington, it would almost certainly have given them foreign recognition. There is indeed a chance that the Union would have also given in, and just let those states go. Many people in the South believe this could have been possible; however, an analysis of a hypothetical scenario in which General Beauregard advanced on Washington in a surprise attack indicates that the war likely would not have concluded. Though the Union army was demoralized and disorganized post-battle, Confederate forces were equally exhausted and faced similar logistical challenges. Unless they could occupy and fortify the city and surrounding areas with sufficiently armed and supplied force, they were at the mercy of the still formidable and strengthening enemy.

Moreover, Washington was heavily fortified, and the Union army had additional troops available for defense, while the Confederate forces were undoubtedly short on supplies and ammunition, exacerbating the difficulties of a march on Washington. Additionally, casualties among key field officers would have further hampered their ability to coordinate and lead such an advance.

The Union forces would have had ample time to fortify their positions and prepare for any potential attacks. They also possessed more troops available for the defense of Washington than the Confederates did for an offensive attack, and reinforcements could be drawn from other regions if necessary, providing a substantial advantage. Unfortunately, the Confederates were at the mercy of the still formidable and strengthening enemy who had a variety of options such as making its own move towards Richmond and/or deranging the Confederacy's logistics.

In conclusion, while the Confederate victory at Bull Run provided a morale boost for the South, it did not translate into a straightforward path to capturing Washington. The logistical difficulties, state of the Confederate forces, and strength of Union defenses rendered such an attempt highly challenging, if not impossible feat.

This factual tale of political intrigue, propaganda,silencing the opposition, printing of fiat currency, suspension of rights, the country and the military being led by incompetent fools, both the House and the Senate clamoring for a war, in which no one ever really wins and throw in a bunch lawyers and bankers, and voila you have a recipe for disaster. Thank you Monica. Outstanding work.

That Lincoln set things in motion and was wholly unprepared for the outcomes is astonishing to me.