Lincoln and the Russians, The Russian Fleet in America Part 5

“The advancement and diffusion of knowledge is the only guardian of true liberty.” ~ James Madison

The arrival of the Russian fleet on American shores in 1863 has been discussed extensively over the years. This event holds considerable importance in both the United States and Russia. Notably, in neither country is this official visit widely acknowledged as having a significant impact on the other. In Russia, it is primarily viewed through the context of European politics, whereas in America, it is often associated with the Civil War. With access to official documents provided by the Russian Minister of the Marine and articles in the Morskoi sbornik, the true motives behind the expedition can now be comprehensively understood.

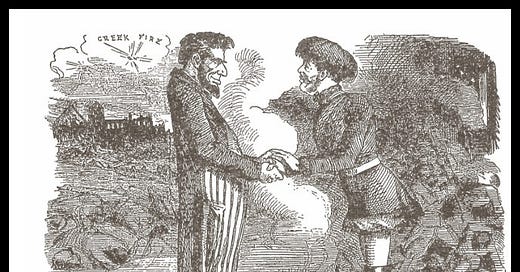

It should be noted that during the period of the American War for Independence, Russia encountered difficulties with Poland. The Poles were dissatisfied with the political conditions imposed upon them by Nicholas I. They anticipated improvements from Alexander II, but as years went by without significant changes, their discontent began to manifest in active resistance against the government. This opposition first became evident on February 25, 1861, and over the next two years, it grew into a formidable movement that concerned all of Europe.

On January 15, 1863, Russian authorities took measures in response to the insurrection. They entered numerous homes in Warsaw and arrested men with the intention of conscripting them into the army. This operation alarmed the European powers, rendering the year 1863 exceptionally critical and raising the threat of a potential general European war.

Prussia sought the friendship of Russia and the end of the uprising, leading to the February 1863 military convention in which both nations agreed to assist each other in suppressing the revolt. France, England, Austria, and other powers opposed Russia's actions towards the Poles. On April 17th, representatives of these governments sent a note of protest to Prince Gorchakov, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs. When this did not have the desired effect, they followed up with a second note in June and a third in August. The diplomatic discussions that ensued are beyond the scope of this text.

The issue is as follows: France, England, Austria, and other powers argued that the Polish question was an international matter, established by the Congress of Vienna, and therefore all signatories of the treaty of 1815 should participate in its resolution. On the other hand, Russia asserted that the question was a domestic matter and would not accept external intervention. Russia agreed to consult directly with Austria and Prussia; however, since Prussia already supported Russia, this agreement effectively amounted to a refusal. The dispute was clearly defined and could be resolved in one of two ways: either one party would withdraw, or conflict would arise.

Russia anticipated the need to defend her position with military force and deemed it prudent to prepare for any eventuality. On January 22, 1862, Grand Duke Constantine, the general admiral of the navy, instructed Popov, who was about to assume command of the Pacific squadron in Asia, that in the event of war between Russia and a more powerful adversary, the weaker ships should be directed to a safe harbor, while the remaining vessels should focus on disrupting enemy commerce. By June 1863, with war appearing imminent, General-Adjutant Krabbe, overseeing the navy in the absence of the grand duke at Warsaw, initiated the development of a campaign strategy.

Despite the apparent strength on paper, the fleet's actual capabilities were limited. It comprised a small Pacific squadron, seven various war vessels at Kronstadt, and a frigate stationed in the Mediterranean. Nearly all these vessels were constructed from wood, and although equipped with engines, the sails remained the primary mode of propulsion, with steam being employed only when absolutely necessary. Bearing this in mind, Krabbe submitted a report to the emperor on July 5th, detailing the potential role of the navy in the forthcoming conflict. He emphasized that historical naval engagements and the current American conflict proved that a small number of well-utilized warships could inflict significant damage on the enemy.

Krabbe suggested that England's avoidance of war with the United States stemmed from concerns over the impact of American cruisers on her merchant marine. He acknowledged that Russia's fleet was insufficient to effectively challenge the combined naval forces of England and France but posited that it was capable of targeting their commerce. He proposed that once England understood Russia's intentions, her stance on the Polish issue would likely shift. To avoid blockade, he recommended deploying the fleet to strategically advantageous locations. This operation required discretion; therefore, ships should depart individually, ostensibly destined for the Pacific or Mediterranean. Even the officers should remain unaware of the true objectives until the last possible moment.

Krabbe concluded by asserting that such a maneuver presented substantial benefits without significant risk. If the fleet failed and was destroyed, Russia would not be disadvantaged as its presence in Kronstadt held limited value. Conversely, if the plan succeeded, considerable advantages would accrue.

The emperor accepted Krabbe’s propositions on July 7th. Orders were immediately given to prepare the ships for foreign service and provide them with funding for two years. Rear-Admiral Stepan Lisovsky, who had extensive naval experience, was offered command of the Atlantic fleet, but he declined. Subsequently, Captain Lisovsky was promoted to rear-admiral and given the command. On July 26th, Krabbe gave Lisovsky his instructions, which had received the approval of the emperor three days earlier. They were divided into fifteen points and were in substance as follows:

“Your fleet is to consist of three frigates, three clippers, and two corvettes. In case of war, destroy the enemy’s commerce and attack his weakly defended possessions. Although you are primarily expected to operate in the Atlantic, yet you are at liberty to shift your activities to another part of the globe and divide your forces as you think best. After leaving the Gulf of Finland proceed directly to New York. It would be preferrable to keep all the ships in that port, but if an arrangement is inconvenient for the American government, you may with the advice of our representative in Washington, dispose of the vessels among the various Atlantic ports of the United States. When you learn that war has been declared it is left to you how to proceed, where to rendezvous, etc. Our minister will help you in the matter of supplies; he will have on hand a specially chartered boat to keep you informed of what is going on. Should you find out on the way that war has broken out begin operation at once. If soon after reaching New York you deem it wise to go to the sea try to keep your fleet together until war is actually declared, but avoid the enemy, even commercial ships, so as to cover your tracks. If through our minister or some other reliable source you are told of the opening of hostilities, dispose of your ships and plan your campaign as may seem best. Captain Kroun is preceding you to America to prepare for your coming. Study the Treaty of Paris so as to be well informed on matters of neutrality. Should you meet with Rear-Admiral Popov consult with his as to the course to be pursued. Communicate in cipher. Hand in person your secret instructions to the officers. Whether there is war or not make a study of the commercial routes, of the strengths and weakness of the European colonies, of desirable coaling stations for our fleet, and of the economic and military importance of our own possessions. These instructions are made purposely general in order to give you a free hand to act according to your judgement and discretion.”

Towards the end of January 1862, Popov left Europe for Hong Kong, arriving there in April. During that summer he sent his ships to different places in the Far East to observe the strength and weakness of European colonies and also give his men the necessary training. He himself sailed from Kamchatka on August 26th, to visit Sitka, Esquimalt, and San Francisco, anchoring there on September 28th. On the return voyage he called at Honolulu and from there steered for Nagasaki, where his fleet was to rendezvous in November. During the winter other cruises were made, and with the experience and knowledge he had acquired, he was in a position to know how to act when called upon.

On April 24th, Krabbe informed him of the critical situation in Europe and advised him to be prepared to attack the enemy at any moment. Gregg, an admiralty officer, notified him on June 3rd that the news of the declaration of war would be telegraphed to him at Omsk (end of the line), where a courier would take it to Tientsin via Kiakhta and Peking. A boat was to be ready at the mouth of the Pei-ho River to meet the courier. Seventeen days later, Krabbe sent a similar dispatch, adding that he could not guarantee that the news would reach Popov before it reached the English admiral. On July 31st, another telegram stated that affairs had reached a most acute stage and that he must stay in close contact with the Russian minister in Peking and remain near Hong Kong or Shanghai where European news was available. Popov had, however, already decided on his course of action. The letter sent by Krabbe on April 24th arrived on July 20th. On the following day, he replied that he was heading to San Francisco and arranged for a collier to be sent to Kodiak Island, Alaska, which he planned to use as one of his bases.

During the middle of July, orders were also telegraphed to the commander of the frigate Oslyabya, at that time in Greek waters, to sail for America. On the way he was to stop in Portugal in order to learn of the state of affairs, to give out the destination as Siberia, to keep on the trade route between Liverpool and the West Indies; and he was told where to join the main body of the fleet, and how to proceed in case of war. About the same time Kroun departed for New York to explain the plan of campaign to Stoeckl, Russian Minister in Washington, and make ready for the coming of Lisovsky.

Since the cruise has nothing to do with American affairs, it is interesting to know why United States ports were selected for base operations. Aside from the friendly relations that had always existed between the two nations there were special reasons why they should draw close to each other at this critical period. Alexander II had freed the serfs; Lincoln was emancipating the slaves. The United States had been invited by France to join the powers in dictating to Russia upon the Polish problem and had declined; Russia had been asked by France to intervein in the Civil War and had refused. Russia was fighting against insurrection; the United States to put down a rebellion. The two governments had similar problems and the same European enemies and that was reason enough why they should feel kindly towards each other.

There were additional reasons why the fleet should proceed to America. To implement Krabbe’s plan, the ships could not remain in Russia, and no other location in Europe would welcome them amicably. Conversely, anchoring in one of the Atlantic ports of the United States would allow for rapid deployment onto the trade routes. This advantage applied to both the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans. Admiral Popov, who had some discretion in his movements, chose to go to San Francisco for several reasons. He had visited there in 1859 and 1862 and established many friendships, and he anticipated a cordial reception upon his return. Every other harbor in the Pacific, including those in Spanish America, was controlled or influenced by the English, Dutch, Spaniards, Portuguese, or French. Entering a Chinese or Japanese port posed the risk of blockade by a superior force, as the opposition would learn of the declaration of war weeks before Popov due to their postal and telegraphic connections extending to Calcutta and rapid boats from Calcutta to Shanghai. Although waiting at one of the Russian stations in the North Pacific was an option, these lacked postal and telegraphic services, as well as provisioning and repair facilities, rendering the fleet severely disadvantaged when it eventually set sail, searching not for the enemy but for sustenance. Considering all these factors, San Francisco emerged as the most suitable port. Despite the presence of numerous English and French individuals in the area, the American populace held favorable views towards the Russians, and their cruisers would be allowed to operate freely.

Upon receiving his orders, Lisovsky communicated to Captain Kroun that he would arrive in New York by September 1st. Prior to entering the harbor, one of his corvettes would be dispatched to assess the situation. If hostilities had not commenced, he would enter with full force; however, if conflict was underway, provisions should be sent to him at the island of Santa Catharina, Brazil, to arrive between November 1st and November 20th. Additionally, supply ships should be present no later than March 15, 1864, in Lobito Bay, Benguela, Western Africa, and by July 15th in San Matias Bay, Port San Antonio, Argentina.

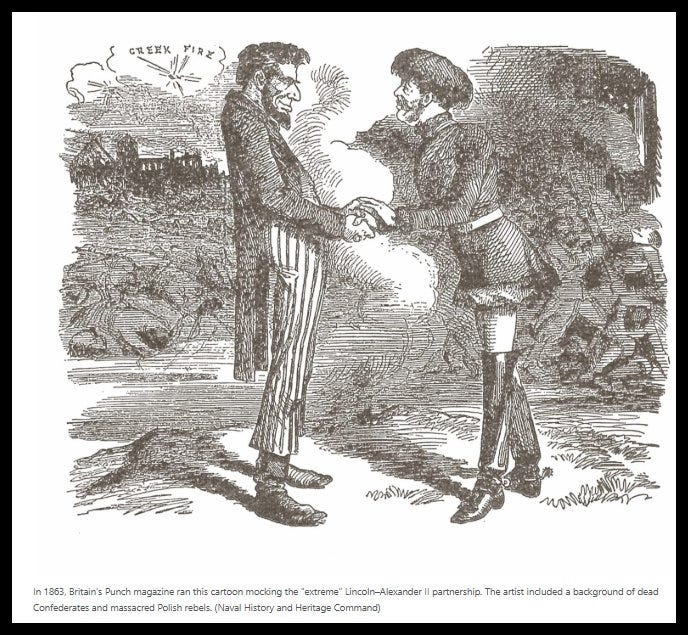

Just before sailing, Lisovsky assembled his officers to inform them of their mission. He decided that the first rendezvous would be in the Little Belt, and from there they would sail together, passing north of Great Britain, and attempt to reach New York before the war. If, however, after leaving the Belt a superior English and French force appeared and followed them, it would indicate an intention to attack as soon as war was declared. In that case, Lisovsky would signal to "separate on the first available occasion," and each ship would use fog or darkness to escape and sail to New York. Should the opposing fleet act unfriendly, such as by ordering the Russians back, the admiral would signal to attack. If crossing the Atlantic revealed that a state of war existed, the campaign plan would be as follows: The Alexander Nevsky would operate between Liverpool and South America, the Peresviet on the England to East Indies route, the Varyag south of the equator, the Vitiaz between Cape Hope and St. Helena Island, and the Almaz to capture enemy vessels sailing between the equator and five degrees north. If war was declared by October 15th, the rendezvous location would be Santa Catharina Island.

The initial plan was to commission seven warships. However, upon inspection, two were found unseaworthy and left behind. Soon after departure, Lisovsky determined that the remaining five ships were not suited for intensive service. The sails were ill-fitting, seawater entered through the portholes, provisions were inadequate, and the sailors lacked experience with long and difficult voyages, leading to hardships and an outbreak of scurvy. On September 24th, the flagship Alexander Nevsky and the Peresvet arrived in New York, followed by the Varyag and the Vitiaz over the next two days. Fifteen days later, the Almaz arrived, and the Oslyabya, coming from the Mediterranean, had reached this port around mid-month.

The arrival of the Russian fleet in New York was unexpected and surprising to London. Brunow, the Russian Ambassador, who apparently had not been informed of this political maneuver, became concerned and believed that this development could lead to war. He expressed his worries to Gorchakov, who began to doubt the wisdom of the action and considered attributing the responsibility to Krabbe. However, Krabbe defended his position, arguing that England would refrain from engaging in conflict if her commerce were jeopardized, and that a few Russian guns in the ocean would exert more influence on England than a larger number in Sevastopol. Brunow and others were instructed to explain, when questioned about the fleet's purpose, that it was on its regular cruise to relieve other ships, and that the vessels would likely remain in the United States waters until the European political situation stabilized. The European powers, particularly England, were left to interpret the situation as they saw fit.

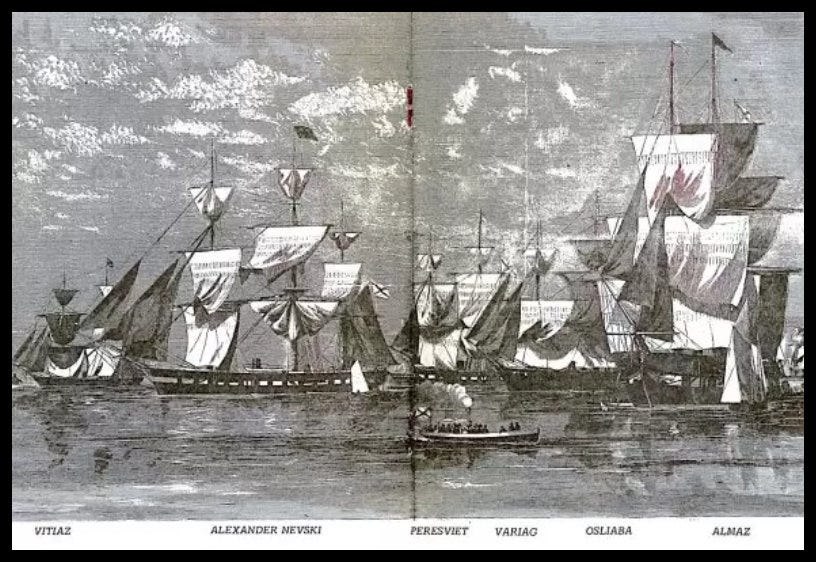

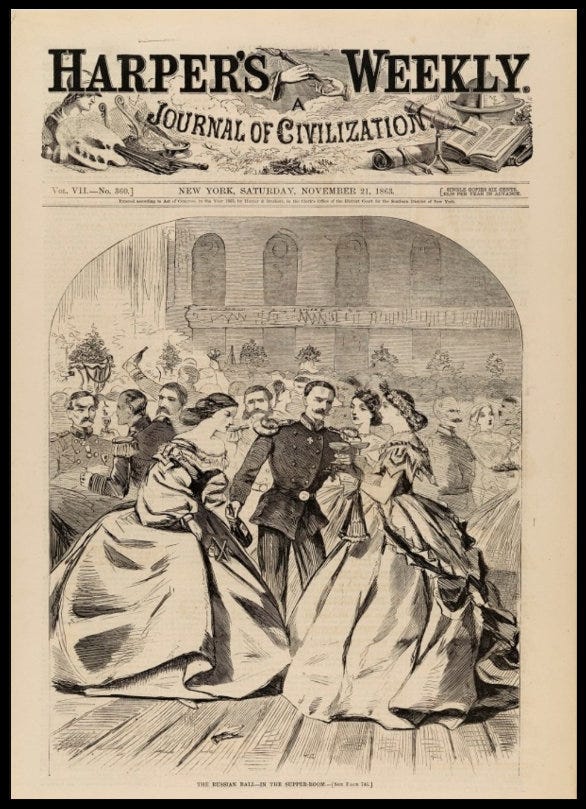

The Russians found a warm welcome upon their arrival in America. When Gideon Welles received official notification of their arrival, he expressed his pleasure to Stoeckl on September 23rd and offered the services of the Brooklyn Navy Yard and other resources of the Navy Department to the Russian admiral. During the fleet's stay in American waters, delegations from New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and other states came to pay their respects. Balls and banquets were held in honor of the officers, and the name of the emperor was lauded as the emancipator of the serfs and a friend of America. In response, the Russians toasted the President and highlighted the historic friendship between Russia and America, deliberately avoiding reference to the European situation. This diplomatic approach reinforced the belief among Americans that the fleet had arrived specifically for their benefit, demonstrating the effectiveness of this strategy. It should be noted that this idea originated within America rather than being brought by the fleet. The Russians maintained friendly and correct relations with the officers of England and France. Lisovsky visited the English and French ministers when they traveled to New York; however, only Lord Lyons returned the visit.

The festivities were not permitted to interfere with the primary objective of the Russian visit. Stoeckl diligently monitored the political landscape and remained well-informed about developments in Europe. By mid-November, it appeared that a critical juncture had been reached, indicating an imminent conflict. Lisovsky requested authorization via telegraph to proceed to the West Indies and strategically divide his forces for potential engagement. In December, Krabbe responded, advising him to maintain his position and assuring him that there was no risk of entrapment. He emphasized that Stoeckl would provide ample warning should evacuation become necessary.

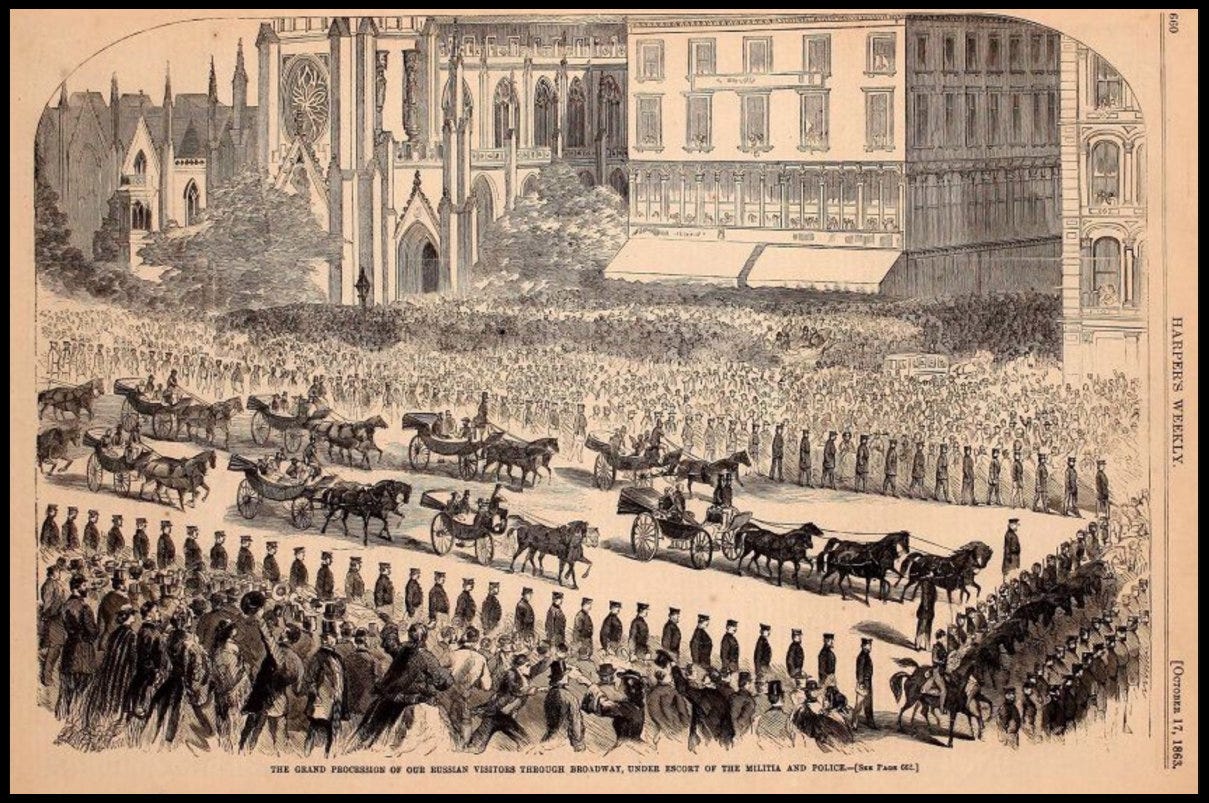

Rear-Admiral Popov, along with his squadron consisting of the corvettes Bogatyr, Kalevala, Rinda, and Novik, as well as the clippers Abrek and Gaidamak, anchored in San Francisco harbor on October 12th and promptly established communication with the legation in Washington. The officers and crew were received with great warmth and enthusiasm both on the Pacific and the Atlantic coasts. These courtesies and hospitality were deeply appreciated by Admiral Popov and his men, who expressed their gratitude through their actions. Approximately three weeks after their arrival at San Francisco, a significant fire erupted in the city, during which the Russian officers and sailors provided valuable assistance in extinguishing it. In recognition of their service, the city council passed resolutions of thanks, which were framed and presented to Admiral Popov.

Furthermore, the Russians were willing to offer additional support, extending beyond aiding San Francisco to defending the nation. During the winter of 1863-1864, San Francisco lacked the protection of a man-of-war, amid reports that Confederate cruisers Sumter and Alabama were planning an attack on the city. In anticipation of this threat, Admiral Popov took preventive measures. He instructed his officers that, should a corsair enter the port, the senior officer of the fleet was to immediately signal "To put on steam and clear for action." Simultaneously, an officer was to be dispatched to the cruiser to deliver the following note:

“According to instructions received from His Excellency Rear-Admiral Popov, commander in chief of His Imperial Russian Majesty’s Pacific Squadron, the undersigned is directed to inform all whom it may concern, that the ships of the above mentioned squadron are bound to assist the authorities of every place where friendship is offered them, in all measures which may be deemed necessary by the local authorities, to repel which may be deemed against the security of the place.”

If no attention were paid to this warning and the cruiser should open fire, it should be ordered to leave the harbor, and in case of refusal, it should be attacked. Russia came very near becoming our active ally.

Copies of these order were sent to Stoeckl and Krabbe, who forwarded them to Gorchakov. The replies and comments of these men bring out in the clearest possible light Russia’s attitude towards the Civil War. In his letter of March 13th to Popov, Stoeckl expressed himself in this manner. As he understood St. Petersburg diplomacy, so far as Russia is concerned, there is neither North nor South but a United States, and therefore Russia has no right to interfere in the internal affairs of another nation and consequentially Popov should keep out of the conflict.

“From all the information to be obtained here (Stoeckl goes on to sat) it would seem that the Confederate cruisers aim to operate only in the open sea, and it is not expected that cities will be attacked, and San Francisco is in no danger. What the corsairs do in the open sea does not concern us; even if they fire on the forts, it is your duty to be strictly neutral. But in case the corsair passes the forts and threatens the city, you have the right, in the name of humanity, and not for political reasons, to prevent this misfortune. It is to be hoped that the naval strength at your command will bring about the desired result and that you will not be obliged to use force and involve our government in a situation which it is trying to keep out of.”

Gorchakov strongly opposed Popov’s plans and advocated for strict neutrality. He had anticipated the potential for such a scenario. In a letter dated January 27, 1862, addressed to Krabbe, he emphasized that while Russia had not officially declared neutrality in the American Civil War, her position was effectively neutral. Russia did not intend to support either the North or the South, and naval officers were to be informed accordingly. This stance was transparent and sincere; Gorchakov had communicated his position to the American government on multiple occasions. In a conversation with Bayard Taylor, the United States chargé d’affaires, on September 27, 1862, he stated, “We desire above all things the maintenance of the American Union. We cannot take any more part than we have done. We have no hostility to the Southern people.” The American public can without difficulty appreciate his stand, especially in view of our own attitude towards the European struggle now going on.

During the winter months, the European war clouds passed away. Russian held firm and won. England was willing to call name but no to fight, and France was helpless without England. Gradually the insurrection was put down and the excitement subsided. Officers of the Russian navy assert that the coming of the fleet to America was, if not altogether, at least in a very great measure, responsible for England’s change of front and consequently for the prevention of war. Before this conclusion can be accepted, evidence from English sources will have to be produced. The claim may have more substance than appears on the surface; the diplomatic aspect of the question as well as the strategic importance of such an expedition needs more investigation. It is true that the Russian papers and many of the statesmen of that time attached a great deal of value to the visit. When the fleet returned to Kronstadt, the emperor reviewed it, thanked the officers for their service and promoted nearly all of them. One naval officer stated that Alexander II, considered this cruise as one of the greatest practical achievements in the history of the Russian navy and one of the noteworthy pages in the history of his reign.

The visit provided significant moral support to the Union cause. At a time when European powers were plotting against the United States and domestic conditions were discouraging, Russia's support was welcomed. It had a positive impact on the people of the North, who viewed the visit as a gesture of friendship. Writing to Bayard Taylor on December 23, 1863, Seward stated: “In regard to Russia, the case is a plain one. She has our friendship, in every case, in preference to any other European power, simply because she always wishes us well, and leaves us to conduct our affairs as we think best.”

Its general effect on the whole nation is excellently told by Rhodes:

“The friendly welcome of a Russian fleet of war vessels, which arrived in New York City in September; the enthusiastic reception by the people of the admiral and officers when offered the hospitalities of the city; the banquet given at the Astor House by the merchants and businessmen in their honor; the marked attention shown to them by the Secretary of State on their visit to Washington “to reflect the cordiality and friendship which the nation cherishes toward Russia”: all these manifestations of gratitude to the one great power of Europe which had openly and persistently been our friend, added another element to the cheerfulness which prevailed in the closing months of 1863.”

On April 26, 1864, Gorchakov told Krabbe that the emperor said there was no longer any need for the fleet to remain in America. Lisovsky was notified the next day to get ready to return home. Somewhat similar orders were dispatched to San Francisco.

During their stay in American waters, the officers visited numerous cities and were consistently welcomed with hospitality. Before departing from the United States, the Russian delegation hosted a reception in Washington, inviting members of the Cabinet, Congress, and many other prominent individuals. The event was notable and one of the major social gatherings of the season. This marked the conclusion of a distinctive and significant episode in Russo-American diplomatic relations.

It is evident that the fleet was not dispatched to America for our benefit. However, it is equally clear that the Union benefited from its presence as if this had been the intention. According to Russian claims, the presence of their ships in our waters prevented them from engaging in a conflict for which they were unprepared. Russia did not intend to assist the Union; similarly, the United States was unaware that it was aiding Russia’s interests. Nevertheless, this occurrence seems to have spared Russia from potential humiliation and conflict.

Bringing the facts and demystifying the events. Thank you.

Thank you. You helped fill the gaps in of my knowledge of this time period. It was amazing how well the Russians played the international chess game of diplomacy and foreign relations. Well done.