Lincoln and His Relationship with the Russians Part 2

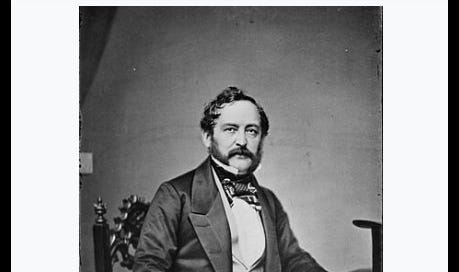

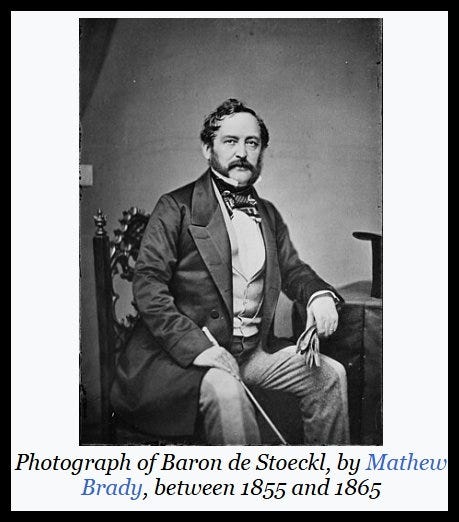

From the translated correspondence of the Baron de Stoeckl, Russian Minister to St. Petersburg at the onset of the Civil War.

Stoeckl and his superiors in Russia’s capital, St. Petersburg, embraced the belief that “the preservation of the Union is for our own best interests.” To further their aims, the Russians would refuse to “take sides with the secessionists prematurely…and not antagonize any State regarding matters which do not involve our interests.”

“The essence of Government is power; and power, lodged as it must be in human hands, will ever be liable to abuse.” ~James Madison

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln led the United States into a partnership with Russia, despite their opposing governments—the American democracy and Czar Alexander II's autocracy. Lincoln saw Russia as an example of despotism but formed an informal yet firm alliance with them.

The Russian-American entente cordiale was a political paradox. To Europe's rulers, the United States was the most dangerous revolutionary government, while Americans viewed Russia as a symbol of despotism. Despite their ideological differences, they united against a common enemy—Great Britain. This alliance prevented European intervention in the American Civil War and stopped an Anglo-French attack on Russia over Poland.

Lincoln saw political collaboration between America's democracy and Russia's despotism as essential for the Republic's welfare. He trusted America and believed in democracy, favoring a strong, united nation to ensure lasting peace. This echoed his 1860 Copper Union speech: “Let us have faith that right makes right, and in that faith let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

Edouard de Stoeckl, who as Chargé d' Affaires significantly contributed to garnering American support for the Russian cause during the Crimean War, was appointed as St. Petersburg's Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States in 1857. He initially arrived in Washington in 1841, serving as attaché or secretary of legation. In 1854, following the death of Alexander Bodisco, who had held the position of the Czar's Minister to the United States for seventeen years, de Stoeckl succeeded him.

In Washington, Stoeckl was frequently referred to as “Baron” despite not being of noble birth. He interacted socially with members of Congress, leading statesmen, and other distinguished individuals. As Russia's representative, he had access to the President and attended White House receptions. He regularly met with the Secretary of State and Cabinet members, engaged with the foreign diplomatic corps, and stayed well-informed through interactions with army officers, journalists, and various other sources.

From this environment, he made detailed observations of events and trends. He regularly corresponded with Prince Gorchakov, the Czar’s Foreign Minister, regarding developments in the United States. Czar Alexander II and the Foreign Minister encouraged him to continue these frequent reports, as Russia was keenly interested in the happenings within the United States—a potential ally among nations.

Additionally, the issue of Russian serfdom shared similarities with the American slavery question. Following the negative result of the Crimean War, it became evident that reform was necessary. Czar Alexander II then made a formal statement to the marshals of the noblesse of Moscow:

“As you yourselves know, the existing manner of possessing serfs cannot remain unchanged. It is better to abolish serfage from above, than to await the time when it will begin to abolish itself from the above. I request you, gentlemen, to consider how this can be put into execution, and to submit my words to the noblesse for their consideration.”

The Emperor, aware of the poor condition of the serfs in his country, took an interest in the ongoing debate in the United States regarding Negro slavery. Stoeckl saw the American skies grow dark with portentous clouds. He heard the halls of Congress ring with the angry debates between free-soil and slavery advocates clashing over the admission of the Territory of Kansas. Reports reached Washington of violence and disorder—men shot; towns sacked; constant deeds of brutality; men from the North and men from the South seemingly losing all sense of their common humanity. “Bleeding Kansas” became a new watchword in the North as people began to realize that the “Kansas War” was but a rehearsal for something much larger. Antagonists of the “popular sovereignty” doctrine pointed to this anarchy-ridden territory as a tragic example of the failure that resulted when the voters of a territory were allowed to choose between freedom and slavery.

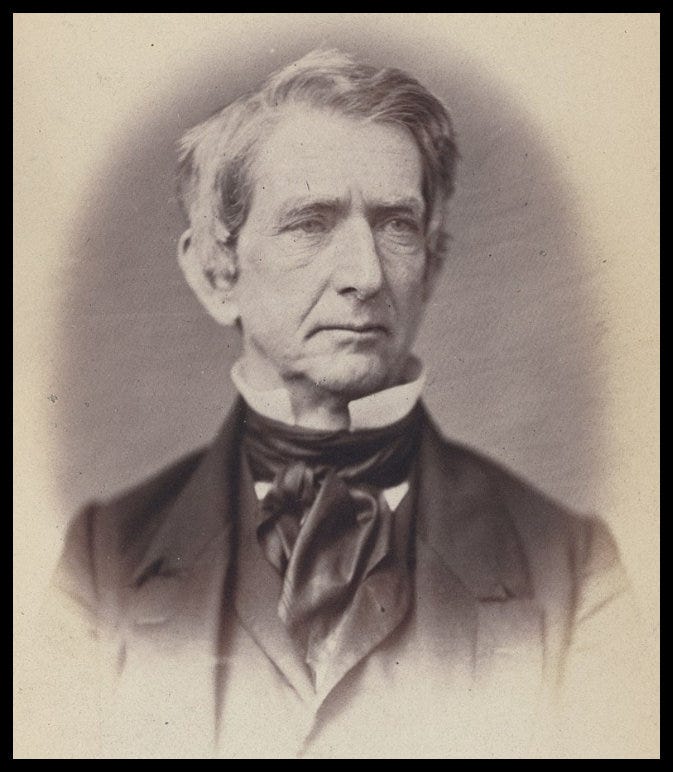

In 1857, during debates about Kansas's admission, Senator Seward harshly criticized using federal troops to enforce laws there. He declared, “When you hear me justify the Czar of Russia's despotism over the oppressed Pole... then you may expect me to vote for men and money to keep the army in Kansas.”

When James Buchanan became the fifteenth President of the United States on March 4, 1857, revolutionary tensions were already brewing in the Capital. At his inauguration ball, Buchanan greeted Russian Minister Stoeckl and reminisced about his time as envoy to St. Petersburg, recalling a conversation with the Empress who had warned against domestic troubles.

Two days after Buchanan's inauguration, the Supreme Court issued the Dred Scott decision, declaring that slaves were property like cattle and that slave owners had rights to their property across the Union. This ruling deemed the Missouri Compromise and anti-slavery laws unconstitutional, igniting the slavery debate further.

Antislavery activists from the North vehemently criticized Chief Justice Taney’s ruling. Horace Greeley in the New York Tribune argued that the Supreme Court's decision deserved no respect. Senator Seward accused the Supreme Court of colluding with President Buchanan and the slave oligarchy to perpetuate slavery in the U.S.

Among the many discussions of the Dred Scott decision, whether in Congress or elsewhere, none were as influential to the public as the opinions expressed during the senatorial campaign of 1858 by Abraham Lincoln of Sangamon County, Illinois, and Senator Stephen A. Douglas. With strong logic, thorough analysis, and persistent argumentation, Lincoln challenged the decision's assertion that slaves have no rights that white men are bound to respect, effectively dismantling its doctrine. His first address during the campaign, known for the “house divided against itself” speech delivered at Springfield in June 1858, provided an examination of the combination of the Nebraska doctrine and the Dred Scott decision.

In the opening paragraph of this speech, Lincoln stated:

“A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fail—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.”

Douglas won the famous State campaign, but Lincoln gained national recognition for addressing key issues. His eloquence resonated widely. Observers, like Stoeckl, noted Lincoln as an emerging political figure in America.

The Supreme Court ruling made a peaceful resolution to the slavery issue impossible, paving the way for John Brown to take direct action. On October 16, 1859, Brown and his followers seized the Harpers Ferry arsenal to free the slaves. This act alarmed the nation, confirming Southern fears of abolitionist intentions.

Brown was captured, tried, and executed on December 2, 1859, becoming a martyr for the abolitionist cause. His death rallied Northern sentiment against slavery, as thousands commemorated him and spread his message of freedom.

In reporting John Brown's dramatic actions to Prince Gorchakov, Stoeckl attributed the cause to the agitation stirred by the New England abolitionists:

“When the sad result of this foray became known, John Brown was proclaimed from the very roof tops as the equal of our Savior. I quote these facts to point out how far Puritan fanaticism can go. Little by little the extreme doctrines of New England have spread throughout the land.”

President Buchanan faced numerous challenges during his administration. He maintained that the people of the North did not have the right to interfere with the institution of slavery in the South, likening it to interference with the serf question in Russia. In a message to Congress, he stated:

“How easy would it be for the American people to settle the slavery question forever and restore peace and harmony to this distracted country. All that is necessary to accomplish the object, and all for which the slave States have ever contended, is to be let alone and permitted to manage their domestic institutions in their own way. As sovereign States, they, and they alone, are responsible before God and the world for the slavery existing among them. For this the people of the North are no more responsible and have no more right to interfere than with similar institutions in Russia and Brazil.”

As the 1860 presidential election began amid talks of an impending crisis, sectional bitterness, and confusion, European diplomats observed the candidates. Senator Douglas was seen as a talented and experienced Democratic leader, while Senator Seward, leading the Republicans, was noted for his antislavery efforts and international knowledge. Jefferson Davis, Edward Everett, James Buchanan, and others were also recognized as statesmen comparable to Europe's political leaders.

Abraham Lincoln, soon to become famous, was viewed poorly by Stoeckl and other foreign observers. They noted his lack of experience in statesmanship, with his only executive role being considered as a “village postmaster.” As soon as the campaign began, warnings of a storm arose. “Elect Lincoln, and the South will secede!” said Southern campaigners. Stoeckl informed St. Petersburg of his concern that “Lincoln's election and party conflicts might cause chaos and disrupt the Union.” He believed Senator Seward was “the best candidate for President,” considering him “the ablest American statesman.”

For months before the conflict began, Stoeckl's letters to St. Petersburg repeatedly mentioned the looming secession of the Southern States. Despite this, he remained hopeful that conservative Americans and material interests would prevent the disaster. He feared Lincoln's election might push proslavery advocates to demand secession but believed that common sense among conservatives would avert this crisis:

“A people, so absorbed in their material interests as Americans are, must realize that federation and not the democracy was chiefly responsible for their prosperity. The industrial classes and farmers of the North and the agricultural class of the South were too dependent on each other to separate. The economic bonds that bind the North and the South were too strong to permit the destruction of the source of their prosperity. And even if these two sections should be so foolish as to encourage separation, the West would never allow it. The rapidly growing West realizes that its continued growth and development depend on the products of the North and the South and the sale of its products in the markets of both sections. The power of the West’s large delegation in Congress is the best guarantee of the permanence of the Union.”

The election took place on November 6. The division within the Democratic Party predetermined the outcome. Upon receiving news that Lincoln had been elected President by the votes of the Northern states against the Southern states, there was significant opposition from the South. Out of approximately 2,000,000 votes cast for him, only 24,000 came from the slave states.

The wires had hardly ceased to trill with the message of death to slavery when the South began to boil with activity. South Carolina, known as "The cradle of secession," where John C. Calhoun's influence lingered, called for a state convention to decide on remaining in the Union. On December 20, the convention unanimously adopted an ordinance declaring, “The Union now subsisting between South Carolina and her other States under the name of the United States of America, is hereby dissolved.”

Stoeckl hastened to impart to his Foreign Office in St. Petersburg a detailed account of South Carolina’s secession from the Union. “The separation of a State numbering scarcely 300,000 white inhabitants would be insignificant were it not the prelude to the complete dissolution of the American Confederation.” He described how provocative acts of New England antislavery leaders succeeded in inflaming the passions of the South to the point that the split became inevitable:

“Everything was thus prepared, and the leaders of the South were awaiting only the opportune time to put their plan for the dissolution of the Union into execution. The election of Mr. Lincoln furnished them with this opportunity…”

Without any doubt, the secession of South Carolina will be followed by other slave States. The dissolution of the Union from this day forward may be considered to be a fait accompli. It is a question now whether the States once separated, can ever be reunited…It is not impossible. There is one circumstance which might react favorably for a course of conciliation. It is the distress which prevails from one end of the Union to the other, and which grows from day to day. This distress has already produced a certain reaction principally in the North, where the people are no less attached to their material interests than to their principles…and it is certain that Mr. Lincoln, if the election were being held today, would lose half of the votes he obtained in November. The people of the North would be disposed to make some concessions…But events are moving too swiftly.”

In the same report Stoeckl went on to place the blame for rupture of the government on both sides:

“I had the occasion recently to speak with one of the Senators of the extremist party of the South, and I expressed to him the opinion that if the slave States would make a joint proposal to the free States, I believe that the North would not be averse to working out a compromise. He replied that it might be true, but that to start discussing compromises concerning a revolutionary movement was tantamount to putting it out of existence, and the South wanted the revolution at all costs. Thus, the two sections are equally responsible for the rupture of the federal pact—the North for having provoked it, and the South for wanting to precipitate events with a speed which makes rapprochement impossible…

The consequences will be horrible for all the parties of the Union. Politically America will cease to be a great nation. Once split in two, the separate sections will not fail to subdivide further. They will thus lose their importance, their present prosperity, and they will not be able to avoid a civil war…

In my opinion all hopes of reconciliation are not yet lost. During my long stay in the United States I have had the opportunity to study American character, and as gloomy as things now appear, it is impossible for me to believe a people so practical and so devoted to their own material interest and prosperity can permit their passions to drag them to the point of sacrificing everything…and it is not unlikely that at the last moment an unforeseen event might yet save the country. I wish it with all my heart because aside from political considerations, we shall deeply regret the downfall of a great nation with which our relations have always been friendly and intimate, and which at one memorable occasion was almost the only power which sympathized sincerely with our cause.”

In his next dispatch to the Russian Foreign Office, a few days later, Baron de Stoeckl told Prince Gorchakov that Francis W. Pickens was the new Governor of the seceded State of South Carolina. The Foreign Minister knew Governor Pickens well, as for two years past the Southern politician had been serving in St. Petersburg as America’s Minister. Governor Pickens, under instructions from the South Carolina secessionist convention, sent three commissioners to Washington to advise President Buchanan officially of South Carolina’s withdrawal from the Union. “They arrived in the capital like envoys from a foreign power,” Stoeckl observed, and presented demands for:

“The transfer of three forts situated at the entrance of Charleston, the principal port of South Carolina. The garrisons of these three forts are composed of only a hundred men or so. Major Anderson, the commanding officer, has constantly asked for re-enforcements. The President refused them on the ground that sending troops to the coast of South Carolina would offend the State. But at the same time, he ordered Major Anderson to defend the fort in case of attack. Placed in a position of peril by the irresolution of the government, this officer adopted the only measure which prudence dictated. He concentrated his men in a single fort and abandoned the others after burying the cannons in the ground and setting the gun carriages on fire.

Angered over Anderson’s skillful maneuver, South Carolina’s convention ordered her militia to occupy the abandoned forts and raise the State banner in place of the nation’s flag. This incident has created a violent sensation. The President, whose subservience to the South is well known, disavowed the acts of Major Anderson, and it was feared that, influenced by Southern Senators, he would give that officer orders to evacuate the fort in which he was entrenched. This would be a shameful capitulation. If Mr. Buchanan would yield to the counsel of the plotters who surround him and commit such an act, the North, regardless of party distinctions, would arise as one to avenge the affront to the national flag.”

In Stoeckl’s next dispatch to St. Petersburg, he wrote of President Buchanan’s proclamation setting aside a day for fasting and prayer to invoke Divine Powers to save the American nation from the perils which threatened it.

“It seems that only the intervention of heaven can stop the onrushing events and avoid the civil war which now appears imminent and almost inevitable. The representatives South Carolina sent to Washington to discuss the peaceful transfer of the ports returned to Charleston after delivering what amounted practically to an ultimatum. South Carolina has already seized the arsenal at Charleston, and other Southern States have seized federal property—even while they are still members of the Union, and their representatives still sit in Congress.”

Stoeckl advised Prince Gorchakov “that the committees named by the Senate and the House to effect a compromise with the South have done nothing. The situation is so menacing that it seems impossible to avoid a civil war. To all intents and purposes, it has already broken out.” He reported the treasury of the United States empty and payments suspended, and American capital refusing to underwrite a government treasury bond issue except at a discount of twenty percent.

After Mississippi cast her lot with secession on January 9, 1861, followed one and two days later by Florida and Alabama, Baron de Stoeckl predicted that “the other States of the South would not be long in following them.” In Georgia, Alexander H. Stephens, one of the South’s ablest statemen, pleaded for remaining in the Union. Before the State’s legislature he urged: “The election of no man, constitutionally chosen to the presidency, is sufficient cause for any State to separate from the Union. Let the fanatics of the North break the Constitution…Let not the South, let not us, be the ones to commit the aggression.” Nevertheless, Georgia followed South Carolina’s example and on January 19 became the fifth State to withdraw. Louisiana became the sixth on January 26, and Texas the seventh on February 1. “If Virginia secedes, she will take with her the other border States,” the Russian Minister wrote, “and disunion will be complete.”

Of Charleston, he added:

“A troublesome incident occurred to aggravate the situation. After hesitating for a long time, the government finally decided to send reinforcements to Major Anderson who is commanding the federal port. At the entry of the Port of Charleston a commercial steamer loaded with supplies was fired upon as it approached the coast of South Carolina and was compelled to seek the open sea. Fortunately, there were no casualties.

In Congress, the event of the week was the communication to Congress in a presidential message. The President reports that the country is headed into full rebellion; that in several States the forts and the federal arsenals are invaded and that the acts of aggression against the federal government are growing every day; that danger is imminent and that it is his function to execute the laws and not to make them; that it is consequently the Congress’ duty to seek means of reestablishing peace by any possible act of conciliation. Mr. Buchanan concludes by saying that the only choice is between compromise and civil war.

This message occasioned heated discussions in the Senate. The most noteworthy speech was made during yesterday’s session by Mr. Seward. He is the head of the Republican Party, and he is designated for the post of Secretary of State under Mr. Lincoln. His speech which may be considered the program of the new administration was listened to with the most rapt attention.

The nation eagerly awaited Senator Seward's address. On January 12, Seward calmly delivered his speech in the packed Senate chamber, wearing a gray frock coat. Stoeckl, observing from the diplomatic corps section, reported to St. Petersburg that Seward’s speech was disappointing. “No one was satisfied by this speech. Both the abolitionists and the secessionists concluded they could expect nothing from the Republicans.”

Stoeckl viewed the address as a vague yet conciliatory and strong plea for preserving the Union, which he described as “the soul of the nation and the source of her prosperity and greatness.”

With frankness, he (Seward), predicted that the dissolution of the Union would be disastrous. It would relegate the separate, rival sections to the status of the small states of Central and South America—constantly in danger of becoming victims of the ambitious great powers of Europe, by saying, “My party and I are prepared to make all sacrifices to preserve the Federal pact. We offer conciliation, concessions and the open hand of peace.”

Stoeckl thought that Seward, who regarded the proposed Crittenden compromise as “unconstitutional and ineffectual, hesitates and contradicts himself at every step. In a word, he has made a number of slight concessions but not what the situation demands…With this speech practically all hope of reconciliation disappeared.”

The same dispatch contains a long analysis of the situation:

“Mr. Seward hesitated a long time before accepting Mr. Lincoln’s offer to become the head of this Cabinet. In finally accepting this post, he believed himself strong enough to silence the storm and pacify the country.

From what I heard from Seward’s intimate friends and what I understood from my own conversations with him, his plan was to break away from the abolitionists and align himself with the moderate conservative party to bring the South back into the Union by granting the concessions she desires. This is unquestionably a statesmanlike program, and if executed vigorously would prove successful.

It was the moment at act, but Seward lacked courage and by his hesitation lost the opportunity of rendering an eminent service to his country. The present administration will last only a few weeks longer…It will then devolve upon Lincoln and his Cabinet to direct affairs and face eventualities. Mr. Lincoln’s administration will be faced with two alternatives: recognition of Southern demands or submitting corrective measures.

In Stoeckl’s opinion, the violent measures preached by the abolitionists have succeeded only in “arousing the passions of the South, throwing the nation into turmoil and perhaps destroying its very existence.” He wrote summarizing the need of each section for the others:

The downfall of the great American Republic will not be the least important event of our epoch, and one wonders what will become of these States when once separated. While united by a federal pact they formed a power of the first order. But who can predict what a civil war will lead to...The struggle must stop someday. The mutual hates must subside and the hardships which are inseparable from a civil war must necessarily produce a reaction. If at this time the American people have not lost their common interests, they will realize that their only salvation is a restored Union. The North needs the South, exploits its commerce, and finds there is a market for its manufactured goods. The $180,000,000 brought in annually by the sale of cotton passes through the hands of the bankers of New York and some other large commercial cities of the free States, which earn large profits therefrom. Strictly speaking, the North can exist without the South, but it will lose the principle source of its wealth and prosperity. The South, from its standpoint, ought to realize that it will find no security for the institution of slavery except in the guarantees granted it by the Constitution.”

Stoeckl was appalled by “the demagoguery, confusion and corruption” which he believed were undermining the very foundation of the government. He placed much of the blame for the deplorable situation upon the Constitution itself, and he predicted that the United States could no longer continue unless the American people made some drastic changes in their Constitution. He had a suggestion that might save the nation:

“In order to consolidate the federal pact it would be indispensable to remodel the Constitution by giving the government more extensive power to restrict universal suffrage; to hold elections less frequently since elections create disorders and anarchy; to enact laws capable of preventing corruption; and to put an end, if possible, to the propagation of the revolutionary and socialist spirit—that plague from the old world which European immigrations has transplanted to this country during the last ten years.”

Having analyzed the situation in the United States, the Russian Minister in another dispatch to St. Petersburg expressed the opinion that if the Crittenden compromise “had been submitted to the people as Senator Crittenden of Kentucky had urged it, it would have approved by a large majority. The representatives of the South have accepted this compromise, but the Republicans have rejected it on the ground that it was in conflict with the principles of their party.” This contention Stoeckl regarded as “nothing but hypocrisy.”

Stoeckl believed that the Southern States were at least brave enough to stand by their convictions, claiming a legal right to secession much like their ancestors who revolted against English rule. He argued that the North's response lacked solid legal backing and neither accepted reconciliation nor proposed necessary measures to save the country.

There was no doubt the Emperor was interested in knowing what Lincoln was doing while the United States government trembled on the brink of disaster. Stoeckl writes:

The President-elect remains at Springfield, Illinois. He scrupulously avoids issuing and opinion regarding the events of the day. To all questions addressed to him, he answers invariably that he is still an ordinary common citizen and not until his inauguration will he announce the program of his administration. His position is hardly to be envied, and the rivalries and jealousies of the heads of his party do not make his task lighter.”

Lincoln was leaving no doubt in the minds of his advocates as to where he stood on the question of the extension of slavery. On December 10, 1860, he wrote to Lyman Trumbull, “Let there be no compromise on the question of ending slavery. If the be, all our labor is lost, and ere long, must be done again…The tug has come and better now than at any time hereafter.” In response to a letter from William Kellogg of the House Committee on the crisis, the President-elect wrote again, “Entertain no proposition in regard to all the extension of slavery. The instant you do they have us under again: all our labor is lost, and sooner or later must be done over.” He sent a similar letter on December 13 to Elihu B. Washburne urging that “on ‘slavery extension’…hold firm, as with a chain of steel.”

Nine days after Seward’s disappointing speech, Stoeckl witnessed another tragic drama in the Senate chamber as Senator after Senator rose and solemnly announced his resignation from his seat and his renunciation of allegiance to the United States. As Senators Jefferson Davis, Yulee, Mallory, Clay and Fitzpatrick marched out, women grew hysterical, and men wept. Not a person present failed to understand the awful significance of the hour. It was as if an invisible Samson were pulling down the pillars of the temple and the whole government structure was about to crumble.

Events were moving with inexorable speed. In a dispatch dated February 2, 1861, Stoeckl reported to the Emperor of Russia:

“The rebellion continues to spread in the South. Louisiana has seceded from the Union. On February 4, the delegates of the secessionist States are to meet at Montgomery, Alabama, to organize a provisional government to elect a President and a Vice President and to form an independent State.

In the border States partisans of the Union and of the secession movement are practically equally divided. The legislature of Virginia requested the other States to send delegates to Washington to endeavor to work out a compromise. The seceded States and the extremists of the North have refuses, but about fifteen States of the Midwest have replied to this appeal and their delegates are scheduled to meet. However, it is doubtful whether they will achieve any satisfactory result. This conference had no legal standing, whatever its decision may be. It will have to be sanctioned by the Congress and the latter is not inclined toward compromise. Public opinion prevailing in the North has found no response from the Capital. Numerous petitions are addressed daily to Congress and the City of New York recently sent a petition signed by 38,000 merchants and industrialists who urgently request the adoption measures calculated to pacify the country. These expressions of public opinion have no effect on the Republicans in Congress. Senator Seward is the only one who manifests any conciliatory attitude. Unfortunately, he has not succeeded in winning over the other members of his Party, who refuse to yield on a single point…”

In a report dated February 12, the Russian Minister continued his account of the crisis:

“The conference of the delegates of the border States and of the North met this week in Washington under relatively favorable auspices. There is no one, however, who dares to predict and favorable results from this meeting.

Congress during last week concerned itself with the tariff question and with a loan of $45,000,000 intended to cover the expenses of the new administration which, coming into power, will find the federal treasury literally empty. It is easier to vote money than to raise it. The last loan was negotiated at a discount of 12 ½ percent. But the government cannot procure its needs even at these burdensome rates. The leading financiers of New York have come to Washington and have declared to Congress that if a settlement were made, they would be ready to advance the funds at the ordinary rates of 6 percent. Otherwise, the government was not to depend on them.

The army and navy have not escaped this general demoralization. Among the officers, a majority of whom are residents of the South, resignations and absences from duty are very prevalent. The commander of the American squadron in the Gulf of Mexico has had to forbid, under threat of extremely severs penalties, any political discussions. Even though suffering a lack of provisions, he sailed to Havana in order to get away from the coast of the United States.

We have just received the news by telegraph that the Congress of the Secessionist States, meeting in Montgomery, Alabama, has named Mr. Jefferson Davis, former Senator of Mississippi, the Provisional President of the Confederation of the South.”

On the day Lincoln started his eleven-day journey from Springfield to Washington, Stoeckl met with Senator Seward to talk about the important situation facing the President-elect, and thus reported the meeting:

“Mr. Seward said to me that the first duty of Mr. Lincoln in taking up the reins of government will be to save his country with his friends if he can, if not, with his enemies. If the influential men of the Republican Party persist in refusing to make concessions, Mr. Lincoln will have to break from them and appeal to all the conservatives who will stand by him.

I asked him if he were sure that the President shared his views. To that he replied: “I am not well acquainted with Mr. Lincoln. However, if he is a man of courage and ability, as I believe him to be, he will quickly realize that it is the only way of saving us from the dangers which surround us. If on the contrary he wishes to adopt measures, all will be lost. I shall not associate myself with such policies, and the responsibility for eventualities will fall on those whose advice he has followed.

Mr. Seward realizes that in the light of the events of the times the program of the Republican Party is impracticable, and with the characteristic wisdom, he feels the necessity of modifying it. By adopting that policy, he has created implacable enemies for himself. Among the twenty-six Republicans who sit in the Senate, he can count on the support of scarcely three fourths. The others have openly declared themselves as opposed to him. These men, distinguished only for their violent fanaticism, are demanding a blockade of all the ports of the South, and the use of force to subdue the seceded States. They know that Mr. Seward is opposed to these extreme measures. And so, they seek to discredit him in the estimate of Mr. Lincoln, and to stop him from participating in the new administration.

Mr. Lincoln left his residence in Springfield and is en route to the National Capital. Since his election he has kept absolute silence about events and about policies which he intends to follow, but during a stop in Cincinnati, he delivered a speech in reply to the greetings of the local authorities. The tenor of this speech could hardly be considered conservative and produced a bad impression on the public. On his arrival there a bitter struggle will arise between opponents to determine who will have the upper hand in the new administration. If the former prevail, there will still remain a chance for peace. With the other eventuality nothing can stop the storm which threatens to break to break the Union into pieces.”

Writing to Prince Gorchakov a few days later, under date of February 28, Baron de Stoeckl reported Lincoln had arrived in Washington two days before:

“During his trip through the Western States, where thanks to the abundant harvest of last year the population was able to escape the disastrous effect of the political crisis, Mr. Lincoln was received with acclaim and not a word was addressed to him regarding the agitations which prevailed in the country.

But it was not the same when he passed through the principal commercial cities of New York and Philadelphia. The greeting which he received from the people of these great cities was appropriate enough for an incoming President, but nothing more. In his welcoming speech the Mayor of New York did not mince his words about the deplorable state into which business had fallen and the hardships which a civil war would bring to the commercial metropolis of the Union. The Mayor of Philadelphia went even further: “I regret,” said he, “that you are not going to stay longer with us and see for yourself the misery among the working classes…due to the greed and to the evil motives of the politicians of all parties. Beware of their advice and count on the people. They will rise up and help you save the country.

Mr. Lincoln showed some embarrassment at the frankness of these two mayors, and he replied that he was not less attached to the Union than they were, and that all his efforts would be devoted to preserving it. It was feared that his trip through Baltimore would give rise to disorder, so he passed through this city during the night without stopping there.”

Sewards remarks about how this would eventually lead to a reliance on and influence from European governments is a telling sign of what is to come.

👏👏👏Well done! An all encompassing look at this difficult time in our history. If it wasn’t so tragic, the comedy of wrong headed thinking and the ramifications of unintended consequences would be rival a Shakespearian tragedy