“I cannot consent to place in the control of others one who cannot control himself.” ~ General Robert E. Lee

Among all prominent individuals involved in the War Between the States, none was more commonly referred to as the self-educated attorney from Illinois who ultimately assumed the role of commander-in-chief of the United States armed forces.

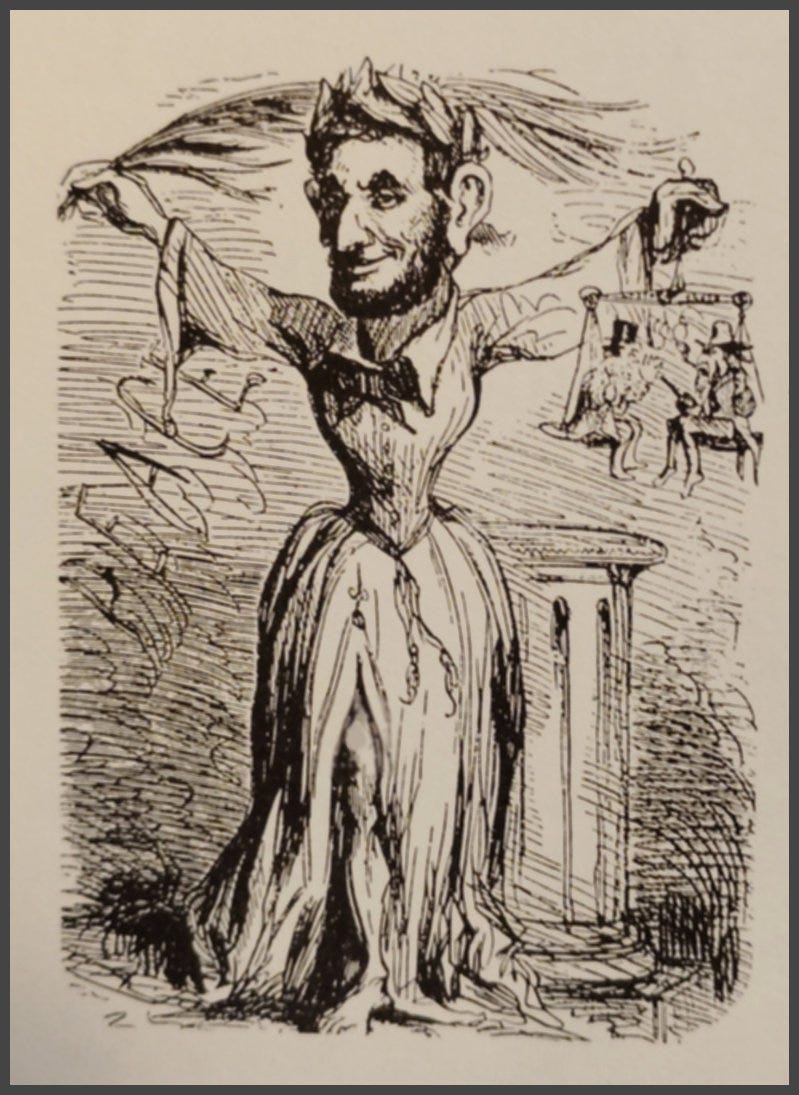

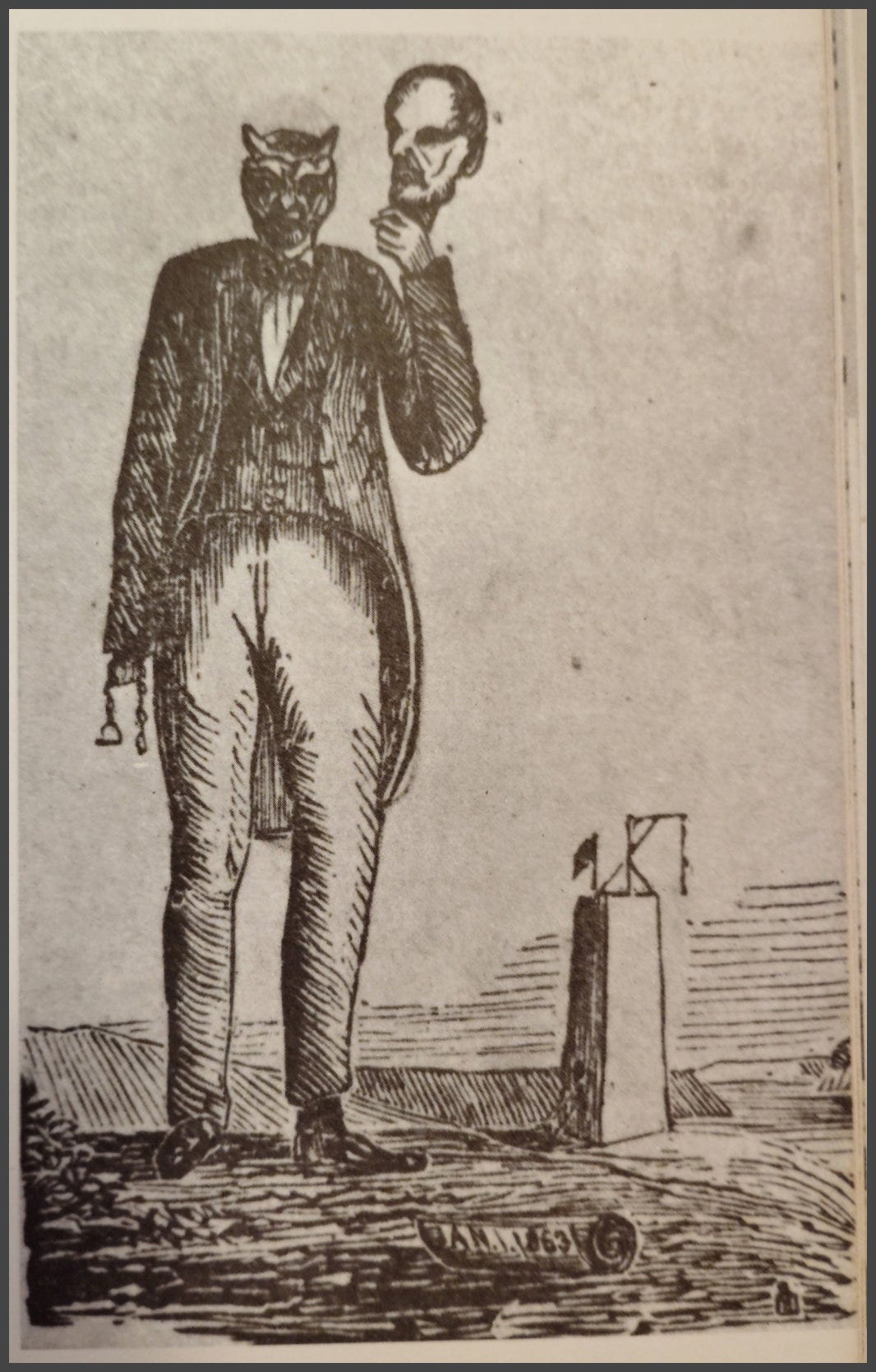

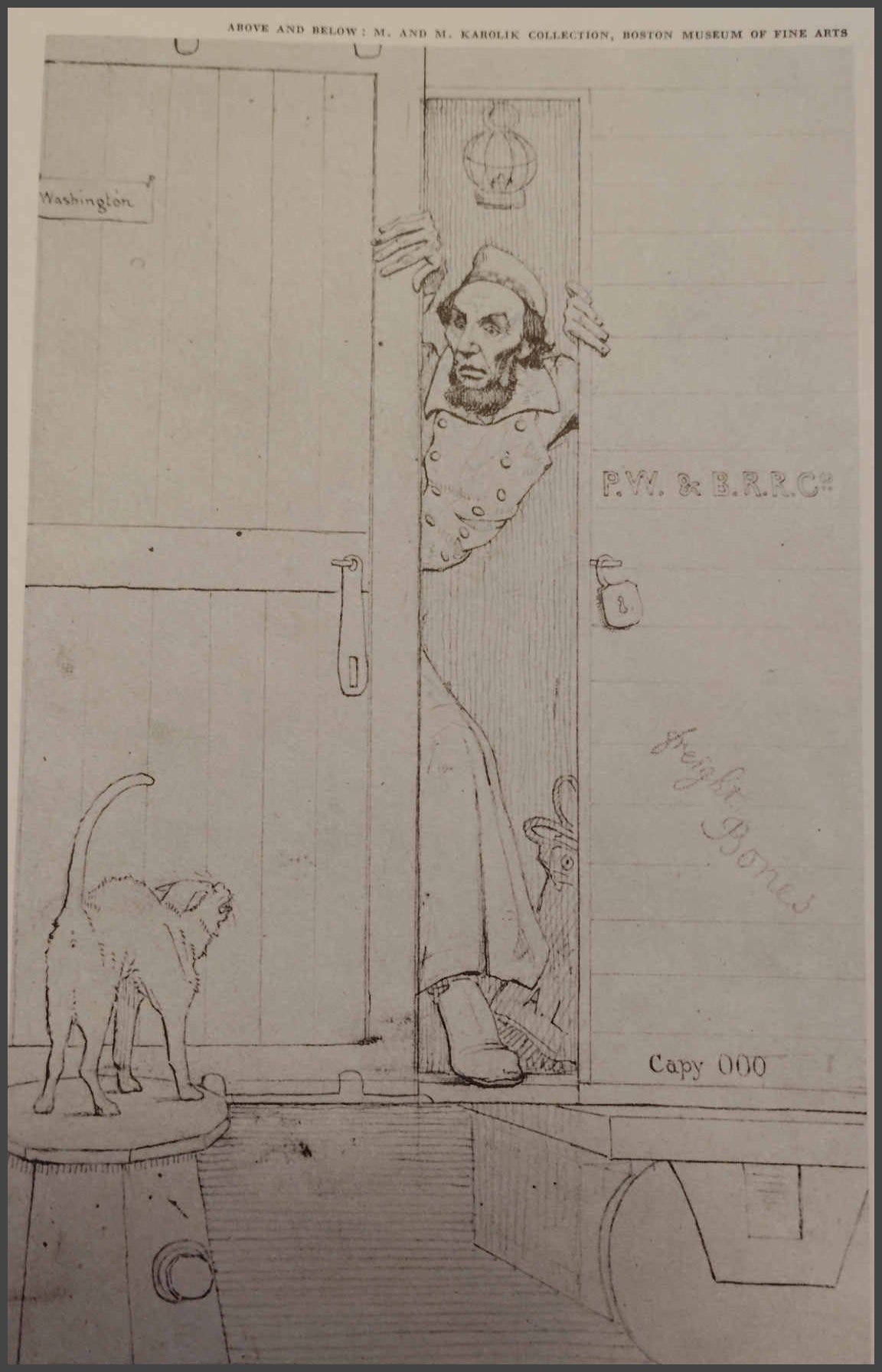

Photographs of Abraham Lincoln are widely recognized today. While he was occasionally photographed prior to 1860, those early images are less familiar to the public. Lincoln was also depicted by cartoonists in various forms, and numerous written portraits were provided by individuals ranging from his classmates to Union soldiers.

Katie Robie, an acquaintance of Lincoln during his late adolescence, noted his notably large hands and feet as well as his exceptionally long arms and legs. In her description of him from this period, she stated:

“His skin was shriveled and yellow. His shoes, when he had any, were low. He wore buckskin breeches; a linsey-woolsey shirt and a cap made from the skin of a squirrel or a coon. His breeches were baggy, and lacked by several inches meeting the tops of his shoes, thereby exposing his shinbone, sharp, blue and narrow.”

A few years later, while working in a general store, Lincoln’s trousers were usually about five inches too short. Though a vest or coat was customary, he wore none—and frequently had only one suspender. “He wore a calico shirt, tan brogans, blue yarn socks and straw hat—old style, without a band.”

D. H. Wilder of Hiawatha, Kansas, didn’t meet the future president until he was a well-known attorney. Wilder was far from impressed with Lincoln, about whom he wrote: “He had legs you could fold up; the knees stood out like that high hind joint of a Kansas grasshopper; the buttons were off his shirt.”

Stephen Trigg, Lincoln’s second law partner who was stingy with words, said only that “He was very tall, gawky, and rough looking; his pantaloons didn’t meet his shoes by six inches.”

Emilie Todd, a younger half-sister of Mrs. Lincoln, was flabbergasted when she first caught sight of her brother-in-law as he entered a room carrying his small son in his arms. After putting the child on the floor, he arose:

“I remember thinking of “Jack and the Beanstalk,” and feared he might be the hungry giant of the story—he was so tall and looked so big with a long, full black cloak over his shoulders, and he wore a fur cap with ear straps which allowed but little of his face to be seen. Expecting to hear “Fe, fi, fo, fum,’ I shrank closer to my mother and tried to hide behind her skirts.”

As a rising Politian, Lincoln managed to stage a series of debates with the great Stephan A. Douglas. One citizen who saw and heard them found the clothing and voice of the Springfield attorney intriguing:

“His clothes were black and ill-fitting, badly wrinkled—as if they had been jammed carelessly into a small trunk. His bushy head, with the stiff black hair thrown back, was balanced on a long and lean head-stalk, and when he raised his hands in an opening gesture, I noticed that they were very large. He began in a low tone of voice as if he was afraid of speaking too loud. He said, “Mr. Cheerman,” instead of “Mr. Chairman,” and employed many other words with an old-fashioned pronunciation.”

A correspondent for the New York Evening Post covered some of the now-famous debates. From him, readers of the newspapers received a terse description of the man they didn’t dream would soon become the nation’s chief executive: “Built on the Kentucky type, he is very tall, slender and angular, awkward even, in gait and attitude. His face is sharp, large-featured and unprepossessing. His eyes are deep set, under heavy brows; his forehead high and retreating, and his hair is dark and heavy.”

Charles Francis Adams first saw president-elect Lincoln on February 14, 1861. Son of John Quincy Adams and grandson of John Adams, the man who soon would become U. S. Ambassador to England was horrified. He said to his family:

“A door opened, and a tall, large featured shabbily dressed man, of uncouth appearance, slouched into the room. His much-kneed, ill-fitting trousers, course stockings, and worn slippers at once caught the eye.”

William H. Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner, offered a retailed word picture that was anything but flattering. According to him, the fifty-one-year-old man then living in Springfield “had no gray hairs, or but few, on his head.” Said the attorney of his partner:

“He was thin, wiry, sinewy, raw, and big heavy-boned, thin through the breast to the back and narrow across the shoulders. Standing, he leaned forward, was what may be called stoop shouldered. His body was well shrunk, cadaverous and shriveled, having very dark skin, dry and tough, wrinkled and lying somewhat in flabby folds; dark hair, the man looking woe struck. He had no spring to his walk; he walked undulatory, up and down in motion. The very first opinion that a stranger would form of Lincoln’s walk and motion was that he was a tricky man, a man of cunning, a dangerous shrewd man, one to watch closely and not to be trusted. His arms and hands, feet and legs seemed in undue proportion to the balance of his body. It was only when Lincoln rose on his feet that he loomed up above the mass of men. He looked like a giant then.”

Walt Whitman paid little or no attention to the clothing of the man destined to become the mysterious central figure of the War Between the States. Concentrating on Lincoln’s face, Whitman said that it was “seem’d and wrinkled yet canny looking.” To the poet, “His dark-brown complexion” and “his black, bushy head of hair and disproportionately long neck” made a fascinating combination.

After the inauguration of 1860, British journalist William H. Russell found the attire of Lincoln somewhat eye-catching. His verbal portrait of the president depicted for readers in England and American chief executive who was “dressed in an ill-fitting wrinkled suit of black, which put one in mind of an undertaker’s uniform at a funeral; around his neck a rope of black silks was knotted in a large bulb, with flying ends projecting beyond the collar of his coat.”

A London colleague of Russell gave British readers an in-depth account of the little-known man appointed to lead the United States during a major crisis, stating:

“To say that he is ugly is nothing; to add that his figure is grotesque is to convey no adequate impression. Fancy a man about six feet high, and thin in proportion, with long bony arms and legs, which somehow seems always to be in the way; with great rugged furrowed hands, which grasp at you like a vice when shaking yours; with a long scraggy neck and a chest too narrow for the great arms at his side. Add to this figure a head, coconut shaped and somewhat too small for such a stature, covered with rough, uncombed hair, that stands out in every direction at once; a face furrowed, wrinkled, and indented as though it has been scarred by vitriol; a high narrow forehead, sunk beneath bushy eyebrows, too bright, somewhat dreamy eyes that seem to gaze at you without looking at you; a few irregular blotches of black bristly hair, in the place where beard and whiskers ought to grow; a close-set thin-lipped, stern mouth, with two rows of large white teeth, and a nose and ears which have been taken by mistake from a head twice the size.

Clothe this figure then in a long, tight, badly-fitting suit of black, creased, soiled, and puckered at every salient point, put on large ill-fitting boots, gloves too long for the long bony fingers, and a hat covered to the top with dusty puffy crepe, and then add to all this an air of strength, physical as well as moral, and a strange look of dignity coupled with grotesqueness, and you will have the impression left upon me by Abraham Lincoln.”

Journalist Noah Brooks, who had known the president before he entered the White House, saw him in Washington and wrote, “His hair is grizzled, his gait more stooping, his countenance sallow, and there is a sunken, deathly look about the large, cavernous eyes.”

Brig. Gen. Carl Schurz, who took time to jot down his impressions of the man whose views and decisions determined the course of the war, was strongly impressed by “that swarthy face with its strong features, its deep furrows, and its benignant, melancholy eyes.”

On Lincoln’s head, wrote Schurz, “he wore a battered ‘stovepipe’ hat. His neck emerged, long and sinewy, from a white collar turned down over a thin black necktie.” His large feet and extremely long arms, concluded the German-born Federal leader, went well with his “lank, ungainly body.”

Frank M. Vancil of Montana was so struck by seeing the President that he wrote a detailed description:

“He was six feet four inches in height, the length of his legs being out of all proportion to his body. When he sat on a chair, he seemed no taller than the average man, but his knees were high in the front.

He weighed about 180 pounds but was thin through the breast and had the general appearance of consumption. Standing, he stooped slightly forward; sitting, he usually crossed his long legs or threw them over the arms of the chair. His head was long and tall from the base of his brain and the eyebrow; his forehead was high and narrow, inclining backward as it rose.

His ears were very large and stood out; eyebrows heavy, jutting forward over small, sunken, blue eyes; nose large, long, slightly Roman and blunt; chin projecting far and sharp, curving upward to meet a thick lower lip which hung downward; cheeks flabby and sunken, the loose skin falling in folds, a mole on one cheek, and an uncommonly large Adam’s apple in his throat. His hair was dark brown, stiff and unkempt, complexion dark, skin yellow, shriveled and leathery.”

Reviewing troops at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, in April 1865, Lincoln made a vivid impression on an officer who kept a detailed diary. He confessed himself to be greatly impressed by the six-foot. Four in commander in chief who “walked with a shambling western slouch” and wore and unusually tall hat that seemed designed to magnify his height. As described only weeks before his assassination, Lincoln’s eyes were set so deeply that their sockets seemed to be bruised. An overwhelming impression was triggered by a close look at the face that sat above a “wry neck.” That day at Harrison’s Landing, he seemed to have “a clown face—a sad face.”

Firsthand descriptions of a few of Lincoln’s general were penned by colleagues and subordinates. Surviving impressions made by Confederate leaders are scarce. In no instance did the war-time appearance of a general officer lead to more than two or three verbal portraits. In this respect as in many others, Abraham Lincoln stands alone among Civil War figures.

Having soaked up the descriptions offered here and having distilled their essence, poet Carl Sandburg offered may be the best summary. Immense armies were directed by a frontiersman whom Sandburg said seemed “like an original plan for an extra-long horse or a lean and tawny buffalo.”

Lincoln’s seemingly total unconcern about his clothing may have stemmed from his early life. On the western frontier where he grew up, it didn’t matter a hill or beans how a boy or girl, man or woman dressed.

Descriptions of his physical characteristics indicate the possibility that he may have had Marfan syndrome. Attempts to conduct DNA testing to confirm whether he carried this rare condition have not been successful to date.

If the genetic disorder was responsible for the physique of the man who put everything he had into preservation of the Union, it also offers tentative explanation of some of his behavior.

All accounts indicate that he ignored repeated attempts to provide for his personal security. His “premonitions” of his own early demise could have been triggered by bodily signals. Cardiac disorders, associated with Marfan syndrome, often lead to sudden and early death. This suggest that had John Wilkes Booth not resorted to a derringer, the ill-dresses and awkward looking man who ran the Civil War might not have lived to complete his hard-won second term in the White House.

In death as in life, visual impressions of the Great Emancipator varied greatly. J. C. Buttre issued for sale a print that depicts Lincoln standing beside a bust of George Washington. As shown in it, however, the Civil War president’s head rests on the body of Andrew Jackson.

James Bodtker, one of Buttre’s competitors, went a step beyond the Jackson/Lincoln composite. His print entitled “The Father, and the Savior of Our Country” shows the first and the sixteenth president standing side by side. Yet the Lincoln who is features here is not the man from Springfield; rather, the body of states’ rights advocate John C. Calhoun of South Carolina is surmounted by the head of Lincoln.

Noted portrait painter Joseph A. Ames wanted to depict the Great Emancipatior but had nothing to work with except a photograph of his head and shoulders. Undaunted, Ames employed a lanky model, dressed him in a frock coat, and proceeded with his Lincoln painting.

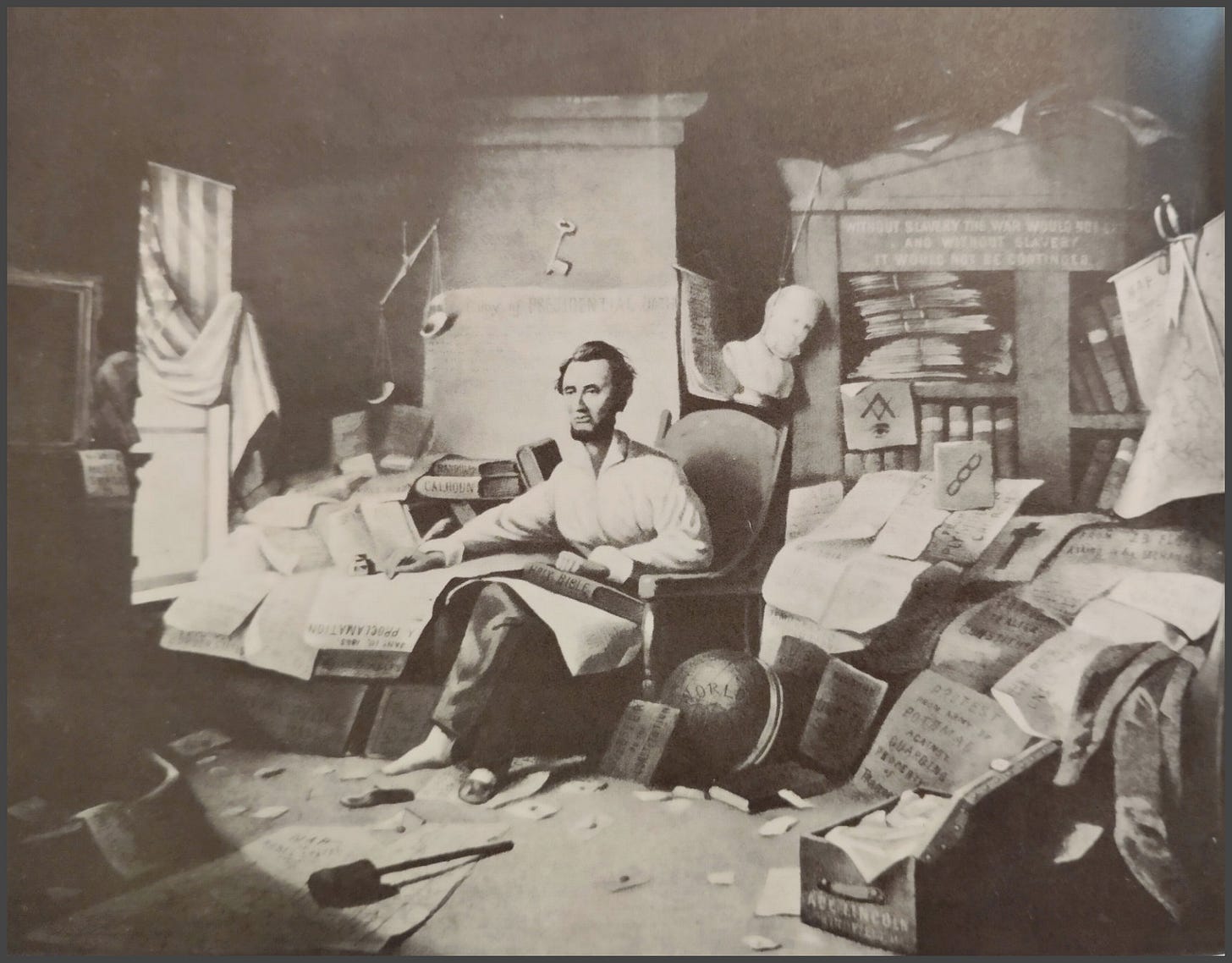

One of the most unusual paintings of Lincoln is held by the Museum of the Grand Army of the Republic in Philadelphia. It depicts the war-time commander in chief leaning on a table and is termed “strange” by some puzzled visitors. (see below)

If it is strange, that’s because the painter who was eager to capitalize on the market created by martyrdom hastily put Lincoln’s head on the body of John C. Fremont. Reproduced, this was sold as a “remembrance portrait” of the slain president.

Even in Washington’s world-famous Lincoln Memorial, awed visitors never fully glimpse the real man who welded a strong central government from a conglomeration of semi-independent states.

Daniel Chester French created the immense statue of the seated commander in chief. Much evidence indicates that the sculptor was familiar with a bronze cast of Lincoln’s right arm and hand that was made on the Sunday after his nomination for the presidency. As the gigantic statue neared completion, French seemed to have found himself unwilling to depict Lincoln’s long and bony fingers.

As a result, visitors from around the world who pause at the Lincoln Memorial do not see the long and bony fingers of the hand, swollen from much shaking, that signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Instead, the most awesome of memorial in Washington exhibits the right hand of the sculptor French.

This was fantastic! I really enjoyed your razor-sharp detail to history (as always), but I also loved reading the descriptions. My goodness, they knew how to write back then!

An excellent work, Monica - well done!

Dear Monica,

Again, another great attention to detail. When researching history, eyewitness accounts like you have in this post and in your posts of April 17, and April 22, 2025, where you quote objective observers like Baron Edouard de Stoeckl, who observed Lincoln on apparently many occasions, a much different image of the man appears than what is taught in late 20th century and early 21st century school books or in the current common media. Eyewitness accounts always have greater credibility than people living 160 years after his death. Also, interesting idea on the Marfan Syndrome. I have never heard that concept before. It prompted me to do some research on the syndrome. FYI, here are some links regarding the physical and mental aspects of the syndrome. Based on these aforementioned eyewitnesses, the physical symptoms sure seem to be present.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/marfan-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20350782

https://march.ai/post/Cf4RqEJk/understanding-the-mental-health-landscape-of-marfan-syndrome/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26526396/

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paolo-Gritti-3/publication/283509176_Psychiatric_and_neuropsychological_issues_in_Marfan_syndrome_A_critical_review_of_the_literature/links/659e640baf617b0d873a9a14/Psychiatric-and-neuropsychological-issues-in-Marfan-syndrome-A-critical-review-of-the-literature.pdf?__cf_chl_tk=lo2.0uPUhF6KCvDpKGPmP6TS2dX4Zb64Kk6tB71o8LM-1753259583-1.0.1.1-9b09rZPp3XJ1Qk93tXLW0FGUuM92LXrFuRzB68rxsQI

This research is in no way comprehensive, but the syndrome appears to have negative physical and mental effects on those afflicted. I hope this helps. Again, another great and thorough post by an excellent researcher and author. You seem to be on the road to recovery. Take care.