Sherman vs Johnston

"I made up my mind that there had been no such army since the days of Julius Caesar." ~General Joe Johnston referring to Shermans Army

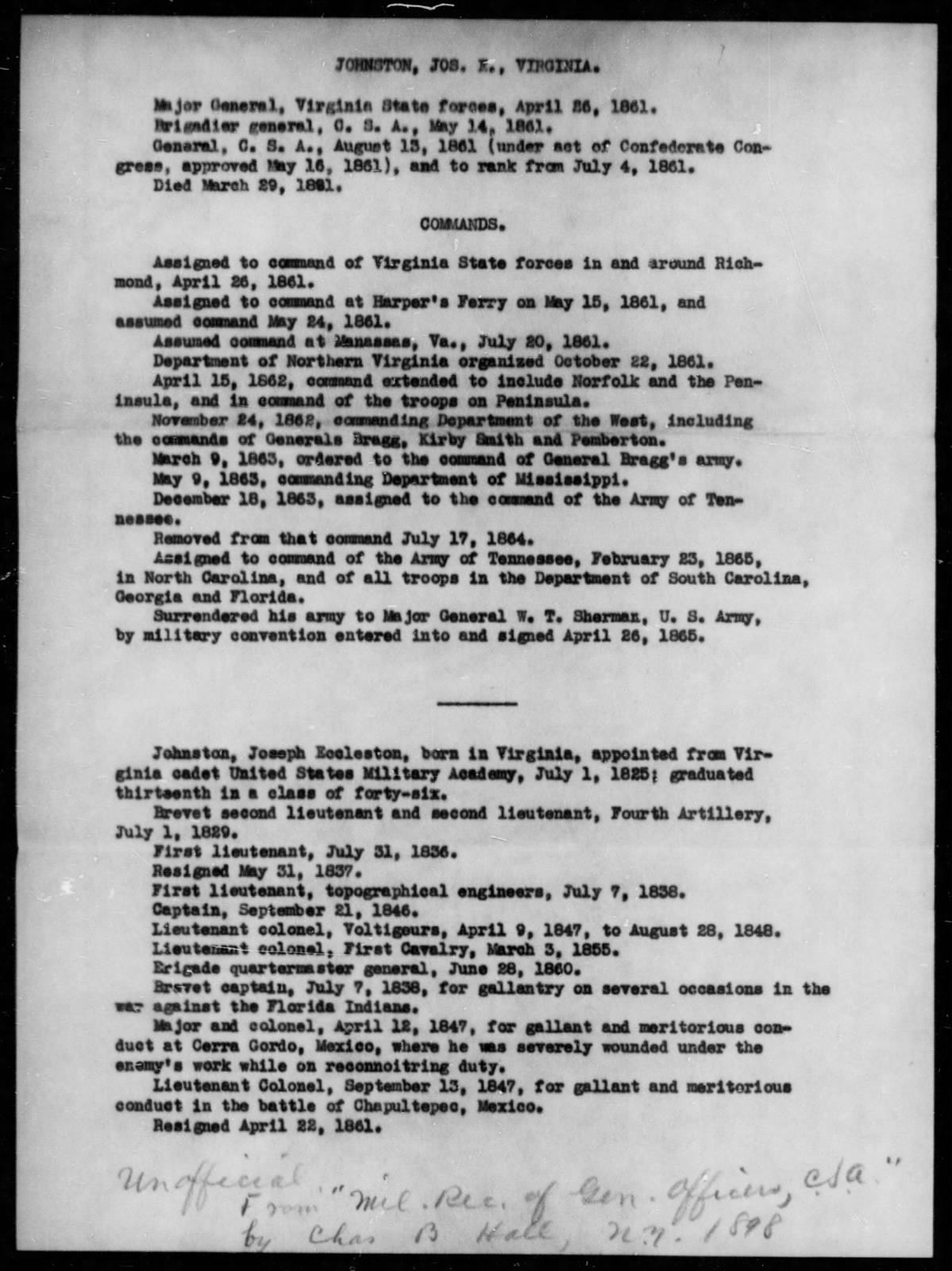

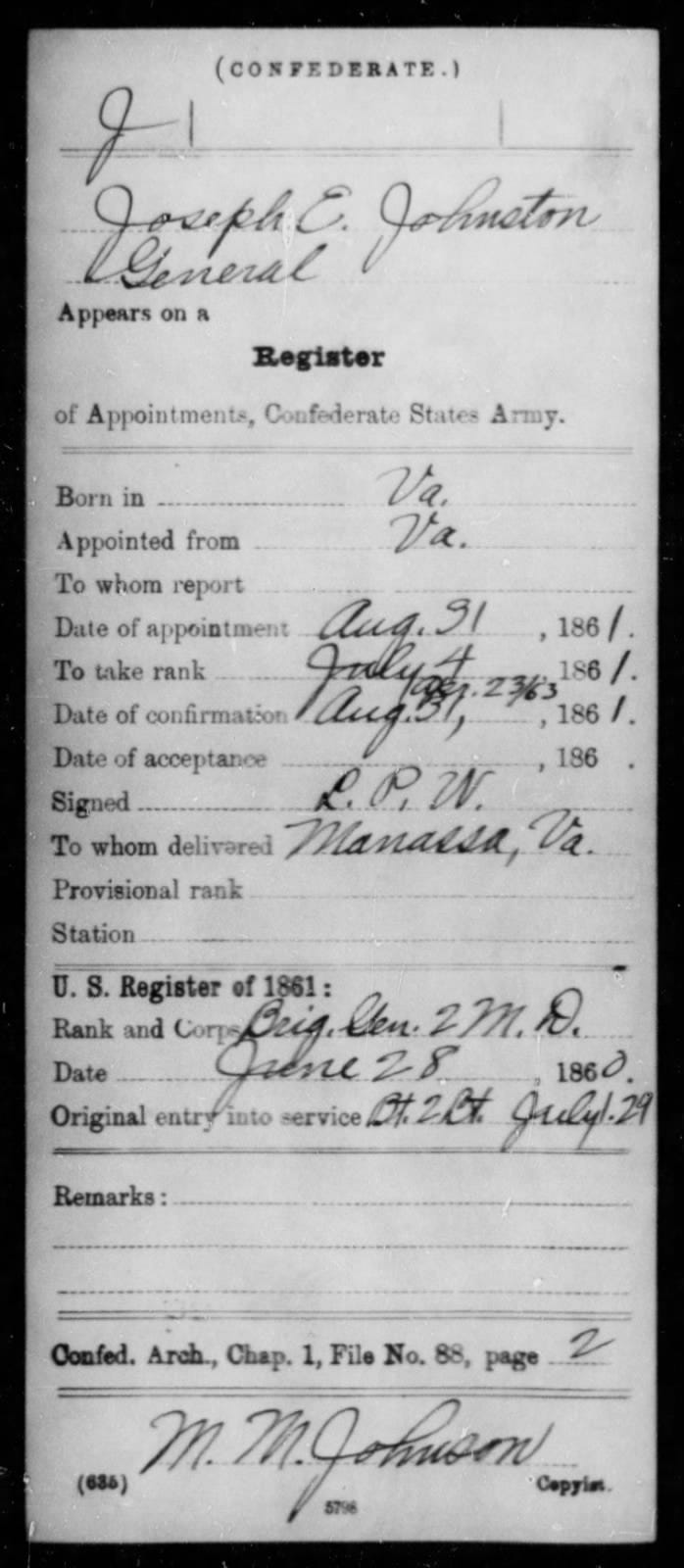

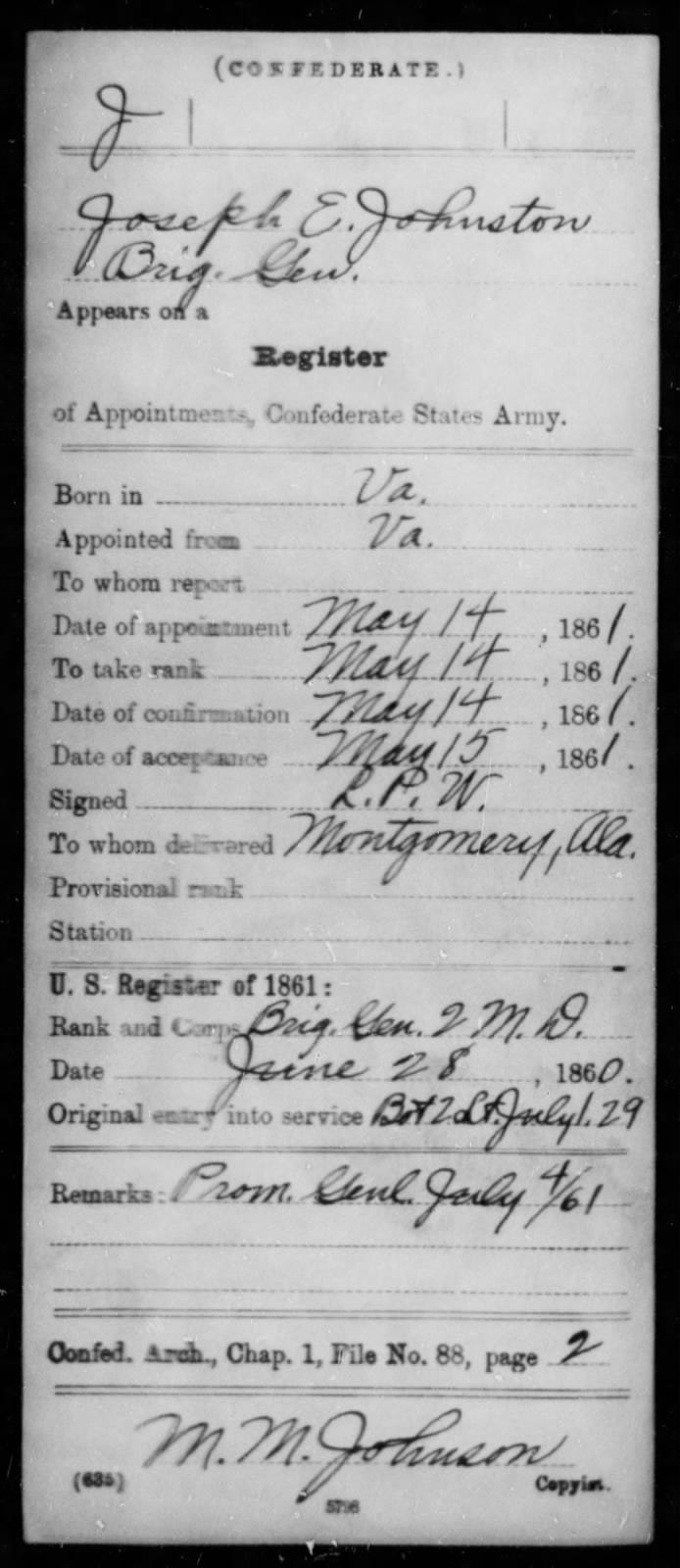

On March 17, 1864, Generals Grant and Sherman met in Nashville, Tennessee, to coordinate a comprehensive campaign targeting the two principal Confederate forces: the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of Tennessee. Grant, appointed as commander of all Union armies, was assigned direct command of the Army of the Potomac to engage with Lee. Concurrently, Sherman, who was appointed by President Lincoln to lead the Military Division of the Mississippi at Grant’s request, assumed command of the Western army, which was designated to advance against Johnson.

It was further determined that both operations would commence simultaneously, with an early start in May. General Sherman consolidated his forces near Chattanooga on the Tennessee River, where the Army of the Cumberland had been stationed for the winter and where a significant battle had taken place in the autumn of 1863. The assembled force consisted of three coordinated armies: the Army of Tennessee, commanded by General James B. McPherson; the Army of Ohio, led by General John M. Schofield; and the Army of the Cumberland, under the command of General George H. Thomas. The Army of the Cumberland was notably larger than the other two combined. Collectively, these formations comprised approximately 99,000 troops, including 6,000 cavalrymen and 4,460 artillery personnel, supported by 254 heavy guns.

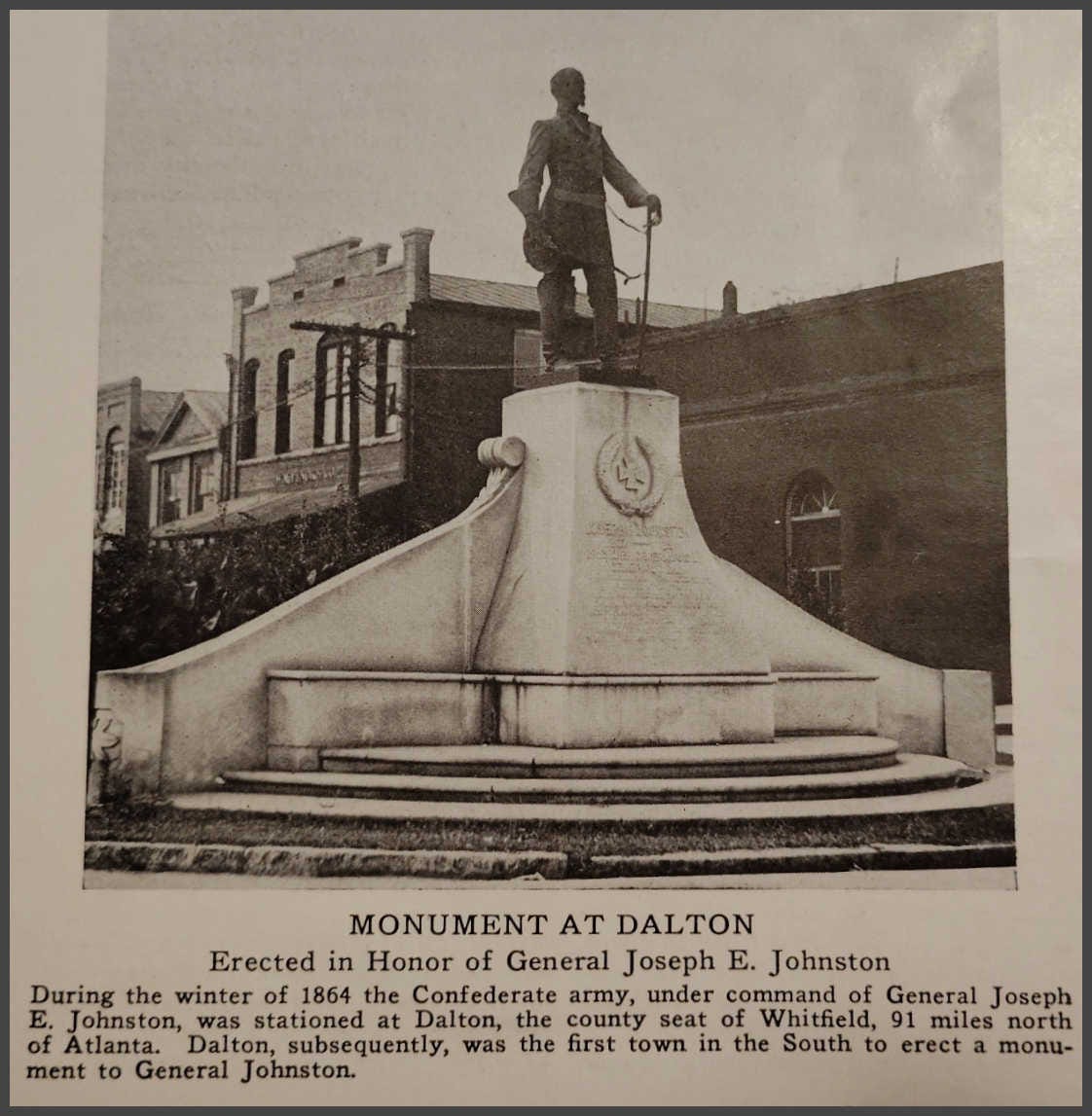

General Joseph E. Johnston’s army, which had spent the winter in Dalton, Georgia, about thirty miles southeast of Chattanooga, was soon positioned against Sherman’s forces. Dalton served as the Confederate army's winter quarters due to events from the previous autumn. Following General Bragg’s defeat at Missionary Ridge and his withdrawal from the Chattanooga area, he retreated to Dalton with the initial plan to remain only overnight. However, when it became clear there was no pursuit the next day, the army continued to occupy Dalton. General Bragg was subsequently replaced by General Johnston.

General Sherman received notification via telegraph of General Grant's plans to advance on Lee near the Rapidan River in Virginia and consequently arranged for his own army to mobilize simultaneously. However, Sherman began his movement two days after Grant, who initiated his campaign in Virginia on May 4th. On May 6th, Sherman broke camp, leading his troops across varied terrain toward the Confederate stronghold. The onset of Southern spring brought blooming landscapes, and the soldiers, eager to end their prolonged inactivity, approached the demanding mission ahead with renewed energy, despite its challenging and violent nature.

Johnston's army consisted of approximately 53,000 troops, organized into two corps under the command of General’s John B. Hood and William J. Hardee. General Polk was en route to reinforce them, which would bring Johnston’s total force to around 70,000 within a few days. The defensive position at Dalton was sufficiently formidable to discourage a direct assault, an approach General Sherman prudently avoided. Instead, Sherman directed Generals Thomas and Schofield to conduct a diversionary demonstration at Johnston's front, while dispatching General McPherson on a flanking maneuver to seize Snake Creek Gap—a strategic mountain pass near Resaca, situated roughly eighteen miles south of Dalton.

Sherman, along with the main portion of his army, soon occupied Tunnel Hill, which faces Rocky Face Ridge, an eastern range of the Cumberland mountains north of Dalton, where a significant part of Johnston’s army was positioned. The Federal commander did not anticipate easily removing his opponent from this fortified location, strengthened by rocks and cliffs that were difficult for any army to traverse under fire. Nonetheless, he directed demonstrations at multiple points, notably at a pass known as Rocky Face Gap. These actions involved soldiers moving over rocks and across ravines while under gunfire and facing stones thrown from above. Overall, these efforts resulted in minimal progress.

Federal forces made little headway against the Confederate stronghold on May 8th and 9th. Concurrently, a significant cavalry engagement occurred on Dalton Road, where Federal commander General E. M. McCook encountered General Wheeler. Colonel LaGrange, leading McCook’s advance brigade, was defeated and subsequently taken prisoner.

Sherman's principal aim in conducting these demonstrations was to engage Johnston and thereby prevent him from intercepting McPherson during the latter's advance toward Resaca. Sherman achieved this objective and, by May 11th, was fully committed to shifting the remainder of his forces to the right flank—mirroring McPherson's maneuver—toward Resaca. He left a detachment from General O. O. Howard's Fourth Corps to occupy Dalton once it was vacated. Upon realizing Sherman's intentions, Johnston promptly recognized the necessity of abandoning his fortifications to intercept Sherman. Utilizing the only two suitable roads, Johnston managed to reach Resaca ahead of Sherman. Due to Johnston’s prior preparation, the town had been fortified, and McPherson was unable to dislodge the garrison or seize the position. The Confederate army subsequently established itself behind entrenchments arranged in a semi-circle of low, wooded hills, with both flanks anchored along the banks of the Oostanaula River.

On the morning of May 14th, the majority of Sherman’s army positioned themselves around the Confederate fortifications, signaling that an engagement was imminent. Hostilities commenced around noon, primarily involving the Fourteenth Army Corps under Palmer from Thomas’ command, alongside Judah’s division of Schofield’s forces. General Hindman’s division from Hood’s corps withstood the main assault, resulting in significant casualties on both sides. Later that day, elements of Hood’s corps were concentrated into a substantial force and launched an offensive against the Federal left flank, causing it to retreat temporarily. However, the Twentieth Army Corps, commanded by Hooker from Thomas’ army, promptly counterattacked the advancing Confederates, ultimately repelling them back to their original positions.

The morning of the following day was characterized by intense skirmishing, which escalated into a significant engagement. Over the course of operations, there was a determined contest for control of a Confederate lunette situated atop a modest elevation. Ultimately, General Butterfield, despite exposure to severe enemy fire, managed to seize the position. However, due to sustained and heavy fire from Hardee’s corps, he was unable to maintain control of the site or extract the four artillery pieces contained within the lunette.

As night approached, General Johnston resolved to withdraw his forces from Resaca. The engagement resulted in approximately three thousand casualties on each side. During the battle, McPherson, acting on Sherman's orders, skillfully maneuvered around Johnston’s left flank in an attempt to intercept the Confederate retreat by securing the bridges over the Oostanaula River. Concurrently, Federal cavalry posed a threat to the railroad to Atlanta, situated beyond the river. Recognizing the severity of these developments, the Confederate commander decided to vacate Resaca. Conducting the withdrawal overnight, he moved his army southward towards the Etowah River, with Sherman closely pursuing. Additionally, Sherman dispatched a division of the Army of the Cumberland, under General Jeff C. Davis, to Rome at the confluence of the Etowah and the Oostanaula, targeting vital machine shops and factories. Davis successfully captured the town and several heavy artillery pieces, destroyed the manufacturing facilities, and stationed a garrison to maintain control.

Sherman sought an open engagement with Johnston, and on the 17th near Adairsville, conditions appeared favorable for such a confrontation. Johnston selected a defensive position, stationed his cavalry, deployed his infantry, and prepared for combat. The Union army advanced, and skirmishing continued for several hours at an intensity comparable to that of a battle. However, Johnston chose to postpone a decisive engagement to a later time.

Several days later at Cassville, Johnston arranged the Confederate forces in battle formation, indicating his intention to initiate a general engagement at this location. He subsequently delivered an inspiring address to the army:

“By your courage and skill, you have repulsed every assault of the enemy…You will now turn and march to meet his advancing columns…I lead you to battle.”

But when his right flank had been turned by the Federal attack, and when two of his corps commanders, Hood and Polk, advised against a general battle, Johnston again decided on postponement. He retreated in the night across the Etowah, destroyed the bridges, and took a strong position among the rugged hills about Allatoona Pass, extending south to Kennesaw Mountain.

Johnston’s choice to alternate between engaging in battle and withdrawing led to dissatisfaction among both his soldiers and residents. The troops were ready to serve but did not understand the strategy of retreating rather than confronting the opposition. Many of the men would have opted for direct engagement over continual withdrawals that prevented them from demonstrating their abilities.

Despite criticism, Johnston demonstrated considerable prudence in his decisions. The Union army possessed a significant numerical and logistical advantage, and General Sherman was recognized for his exceptional strategic acumen. Johnston based his strategy on several possible outcomes: the opportunity to engage an isolated segment of Sherman’s forces; the possibility that Sherman would be sufficiently weakened by the necessity of defending the extended supply line through Chattanooga, Nashville, and as far as Louisville, thereby increasing vulnerability in open battle; or that Sherman might commit to a direct assault while Johnston held a fortified and virtually unassailable position, which was currently the case.

Sherman was not yet prepared to accept such a risk. When Johnston established his fortified position at and beyond Allatoona Pass, the Union commander chose, after allowing his troops several days of rest, to advance toward Atlanta by way of Dallas, located southwest of the pass. The Federal army was provisioned with rations sufficient for a twenty-day period without direct lines of communication. Maintaining Sherman's railroad connection with the North presented a significant logistical challenge throughout the campaign. As the Confederates retreated southward, they destroyed sections of the railway; however, Federal engineers followed closely behind, repairing tracks and reconstructing bridges nearly as rapidly as the army progressed.

Sherman's advance toward Dallas prompted Johnston to withdraw from the Allatoona hills. On May 23rd, the Federal commander reported from Kingston: “I am already within fifty miles from Atlanta.” Nevertheless, it would be several weeks before he reached the city, as numerous engagements with his principal adversary lay ahead. By May 25th, both armies were positioned near New Hope Church, approximately four miles north of Dallas. Over the following three to four days, frequent skirmishes occurred, though no engagement rose to the level of a formal battle.

Late in the afternoon of the first day, Hooker made a vicious attack on Stewart’s division of Hood’s corps. For two hours the battle raged without a moment’s cessation. Hooker being pressed back with heavy loss. During those two hours he held his ground against sixteen fieldpieces and five thousand infantries at close range. The name “Hell Hole” was applied to this spot by the Union soldiers.

The following day, skirmishes occurred in various locations along the dividing line between the two armies. The primary activity of the day was constructing entrenchments in preparation for a possible general engagement. The terrain posed challenges for such a confrontation; a continuous series of hills covered with primeval forests provided limited opportunity for both armies—spanning nearly ten miles from Dallas to Marietta—to engage simultaneously along the entire front.

A severe contest occurred on the 27th, near the center of the battle lines, between General O. O. Howard on the Federal side and General Patrick Cleburne on the part of the South. Dense and almost impenetrable was the undergrowth through which Howard led his troops to make the attack. The fight was at close range and was fierce and bloody, the Confederates gaining the greater advantage.

The following day, Johnston launched a significant offensive against the Union right under McPherson near Dallas. However, McPherson's forces were well fortified, and the Confederate attack was repelled with heavy casualties. During the three to four days of engagements, Federal losses were estimated at approximately 2,400 men, while Confederate casualties were likely higher.

In early June, Sherman secured Allatoona and established it as a secondary supply base following repairs to the railroad bridge over the Etowah River. In response, Johnston repositioned his left flank to Lost Mountain, extending his right beyond the railroad line—a front spanning ten miles, which exceeded the capacity of his available forces. After receiving reinforcements, Johnston's army totaled approximately seventy-five thousand troops. By June 1st, Sherman commanded nearly one hundred and thirteen thousand men, and on June 8th, his numbers increased further with the arrival of a cavalry brigade and two divisions from the Seventh Corps, led by General Frank P. Blair, who had advanced from Alabama.

So multifarious were the movements of the two great armies among the hills and forests of that part of Georgia, that it is impossible for us to follow them. On the 14th of June, Generals Johnston, Hardee, and Polk rode up the slope of Pine Mountain to reconnoiter. As they were standing, making observations, a Federal battery in the distance opened on them and General Polk was struck in the chest with a Parrot shell. He was killed instantly.

General Polk was greatly beloved, and his death caused a shock to the whole Confederate Army. He was a graduate of West Point; but after graduation he took orders in the church and for twenty years before the outbreak of the war was Episcopal Bishop of Louisiana. At the outbreak of the war, he entered the field and served with distinction to the moment of his death.

During the next two weeks there was almost incessant fighting, heavy skirmishing, and sparring for position. It was a game of military strategy, played among the hills and mountains and forests by two masters in the art of war. On June 23rd, Sherman wrote, “The whole country is one vast fort, and Johnston must have fully fifty miles of connected trenched…Our lines now in close contact, and the fighting incessant…As fast as we gain one position, the enemy has another all ready.”

Sherman, aware of his numerical advantage, sought a decisive engagement against his opponent. However, Johnston employed effective strategies to avoid direct confrontation. He maintained strong defensive positions and avoided unnecessary risks. Eventually, Sherman, growing impatient, ordered a general frontal assault despite Johnston's well-fortified position on the slopes of Kennesaw Mountain—a tactical situation that aligned with the Confederate commander's intentions.

The desperate battle of Kennesaw Mountain occurred on the 27th of June. In the early morning hours, the boom of a Federal cannon announced the opening of a bloody day’s struggle. It was soon answered by the Confederate batteries in the entrenchment along the mountainside, and the defeating roar of the giant conflict reverberated from the surrounding hills. About nine o’clock the Union infantry advance began. On the left was McPherson, who sent the Fifteenth Army Corps, led by General John A. Logan, directly against the mountain. The artillery from the Confederate trenches in front of Logan cut down his men by hundreds. The Federals charged courageously and captured the lower works but failed to take to higher ridges.

The primary offensive of the day was conducted by the Army of the Cumberland, led by Thomas. Newton's and Davis's divisions were notable participants in the operation against General Loring, who succeeded Polk. At a certain point on the ridge, General Cleburne maintained a line of breastworks that was supported by artillery on the flanks. An assault was attempted against this position, but it failed and resulted in significant losses.

When the word was given to charge, the Federals sprang forward and, in the face of a deadly hail of musket balls and shells, they dashed up the slope, firing as they went. Stunned and bleeding, they were checked repeatedly by the withering fire from the mountain slope; but they reformed and pressed on with dauntless valor. Some of them reached the parapets and were instantly shot down, their bodies rolling into the Confederate trenches among the men who had slain them, or back down the hill whence they had come. General Harker, leading a charge against Cleburne, was mortally wounded. Many of his men fell with the General, and those who did not, were driven back after sustaining many injuries.

This assault on Kennesaw Mountain cost Sherman three thousand men and won him nothing. Johnston’s loss probably exceeded five hundred. The battle continued for another two and a half hours. It was one of the most reckless and daring assaults during the war, and it did not greatly affect the final result of the campaign.

Under a flag of truce, on the day after the battle, the men of the North and of the South met on the gory field to bury their dead and to minister to the wounded. They met as friends for that moment, and not as foes. It has been recorded that there were instances of fathers and sons, one in blue and the other in gray, and brothers on opposite sides, meeting one another on the bloody slopes of Kennesaw. Tennessee and Kentucky each contributed thousands of men to both sides during the conflict, and families were sometimes divided between opposing allegiances.

During this period, three weeks of continuous rainfall affected both armies, significantly hampering their operations. The soldiers’ uniforms, equipment, and supplies became saturated with water and mud. Nevertheless, combatants from both the North and the South persisted in their efforts on the mountain slopes, each side focused on achieving tactical advantage over the other.

After his significant setback at Kennesaw Mountain, Sherman concluded that attacking his formidable opponent in well-fortified positions would not lead to success. He reverted to his earlier strategies, opting to outflank Johnston as he had previously done at Dallas and Allatoona Pass. Sherman then targeted Johnston’s supply lines connecting to Atlanta, effectively threatening his communications and resources. This maneuver proved successful; within a few days, Johnston abandoned Kennesaw Mountain.

Johnston moved to the banks of the Chattahoochee, Sherman following in hope of catching him while crossing the river. But the wary Confederate had again, as at Resaca, prepared entrenchments in advance, and these were on the north bank of the river. He hastened to them, then turned on the approaching Federals and defiantly awaited attack. But Sherman remembered Kennesaw and there was no battle.

Military maneuvers, including feints, sparring, and flanking actions across the hills and forests, persisted over several days. The initial objective in early July was to secure a crossing of the Chattahoochee River. On July 8th, Sherman directed Schofield and McPherson to cross approximately ten miles upstream from the Confederate position. Johnston executed his river crossing the following day, with Thomas subsequently doing the same.

Sherman's situation offered little reassurance. Although, over the course of two months, he had steadily advanced his forces more than one hundred miles toward Atlanta, the primary objective of the campaign—there remained significant risk. The sole railroad line connecting his army with the North, responsible for transporting supplies from Louisville over a distance of five hundred miles for one hundred thousand troops and twenty-three thousand animals, was vulnerable to potential disruption by Confederate raiders at any time.

The protection of the Western and Atlantic Railroad remained a constant strategic priority for Sherman. Forrest and his cavalry were positioned in northern Mississippi, prepared to disrupt the railroad infrastructure as soon as Sherman's advance toward Atlanta created an opportunity. To prevent this, General Samuel D. Sturgis, with eight thousand troops, was sent from Memphis against Forrest. He met with him on the 10th of June near Guntown, Mississippi, but was sadly beaten back and driven back to Memphis, one hundred miles away. The affair, nevertheless, delayed Forrest in his operations against the railroad, and meanwhile General Smith’s troops returned to Memphis from the Red River expedition, somewhat late according to the schedule, but eager to join Sherman in the advance on Atlanta. Smith, however, was directed to take the offensive against Forrest, with fourteen thousand troops, and in a three-day fight, demoralized him badly at Tupelo, Mississippi, July 14th-17th. Smith returned to Memphis to make another deployment under Sherman. He was subsequently reassigned to Missouri to assist Rosecrans, as Confederate General Price was conducting significant operations in that region.

To avoid defeat and to win the ground he had gained had taxed Sherman’s powers to the last degree and was made possible only through his superior numbers. Even this degree of success could not be expected to continue if the railroad to the North should be destroyed. But Sherman must do more than he had done; he must capture Atlanta, this Richmond of the far South, with its cannon foundries and its great machine shops, its military factories and extensive army supplies. He must divide the Confederacy north and south at Grant’s capture of Vicksburg had split it east and west.

Sherman must have Atlanta, for political reasons as well as military purposes. The country was in the midst of a presidential campaign. The opposition to Lincoln’s reelection was strong, and for many weeks it was believed on all sides that his defeat was inevitable. At least, the success of the Unions arms in the field was deemed essential to Lincoln’s success at the polls. Grant made little progress in Virginia and his terrible repulse at Cold Harbor, in June had cast gloom over every Northern state. Farragut was operating in Mobile Bay; but his success was still in the future.

The eyes of the supporters of the of the great war president turned longingly, expectantly, toward General Sherman and his hundred thousand men before Atlanta. “Do something—something spectacular—save the party and save the country thereby from permanent disruption!” This was the cry of the millions, and Sherman understood it. But withal, the capture of the Georgia city may have been doubtful but for the fact that at a critical moment the Confederate president made a decision that resulted, unconsciously, in a decided service to the union cause. He dismissed General Johnston and put another in his place, one who was less strategic and more impulsive.

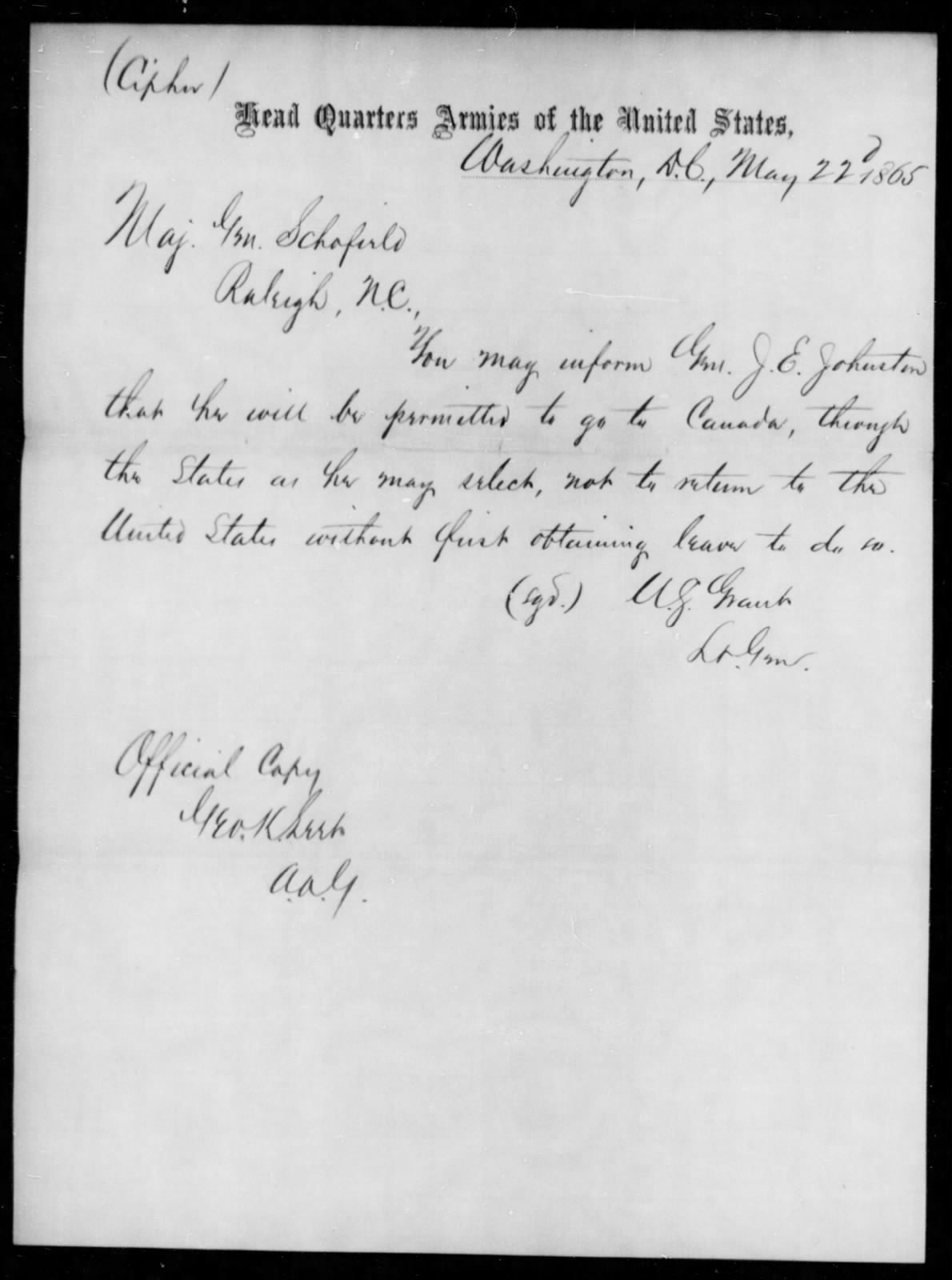

Jefferson Davis disagreed with General Johnston’s military decisions and cited Johnston’s ongoing withdrawal before the Northern army as grounds for his removal. On July 18, Davis appointed General John B. Hood to lead the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Hood, a West Point graduate from the class of 1853 and peer of McPherson, Schofield, and Sheridan, had served in the Confederate army since the war began. He was recognized for his willingness to engage in battle, and it was expected he would shift from Johnston's strategy to more direct confrontations with Sherman’s forces, which subsequently occurred.

While Hood did not match Sherman in a strategic approach, he was not lacking in resolve. However, his aggressive tactics were not well aligned with the context or the terrain, particularly given that Sherman’s army was significantly larger than his own.

Two days after Hood took command of the Confederate army he offered battle. Sherman’s forces had crossed Peachtree Creek, a small stream flowing into the Chattahoochee, but a few mile from Atlanta, and were approaching the city. They had thrown up slight breastworks as were their custom, but they were not expecting an attack. Suddenly, however, about four o’clock in the afternoon of July 20th, an imposing column of Confederates burst through the woods near the position of the Union right center, under Thomas. The Federals were soon at their guns. The battle was short, fierce, and bloody. The Confederates made a gallant assault, but were pressed back to their entrenchments, leaving the ground covered with dead and wounded. The Federal loss in the battle of Peachtree Creek was placed at over seventeen hundred, the Confederate loss being much greater. The battle had been planned by Johnston before his removal, but he had been waiting for the strategic moment to fight it.

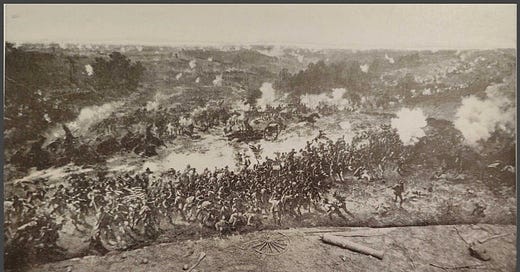

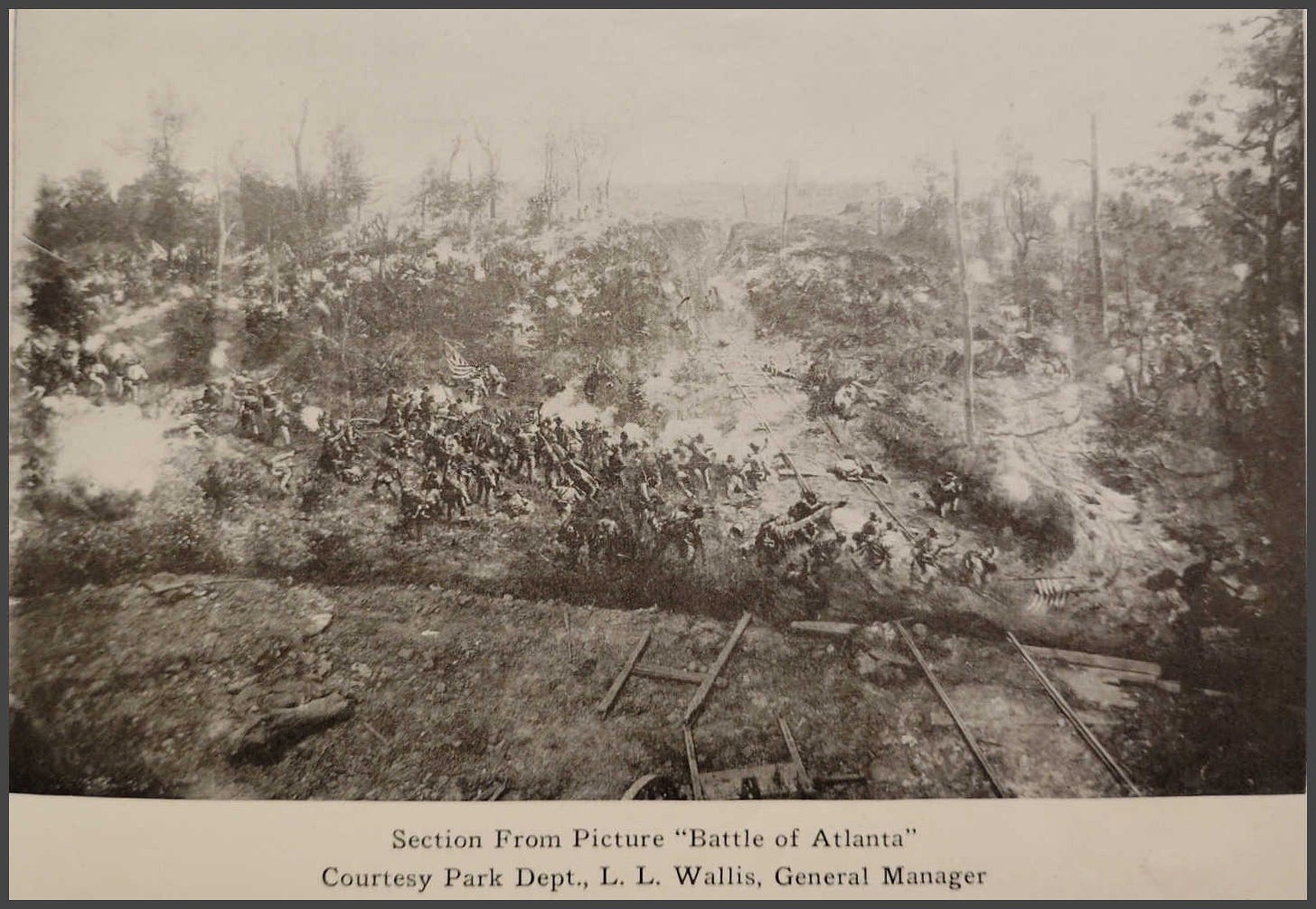

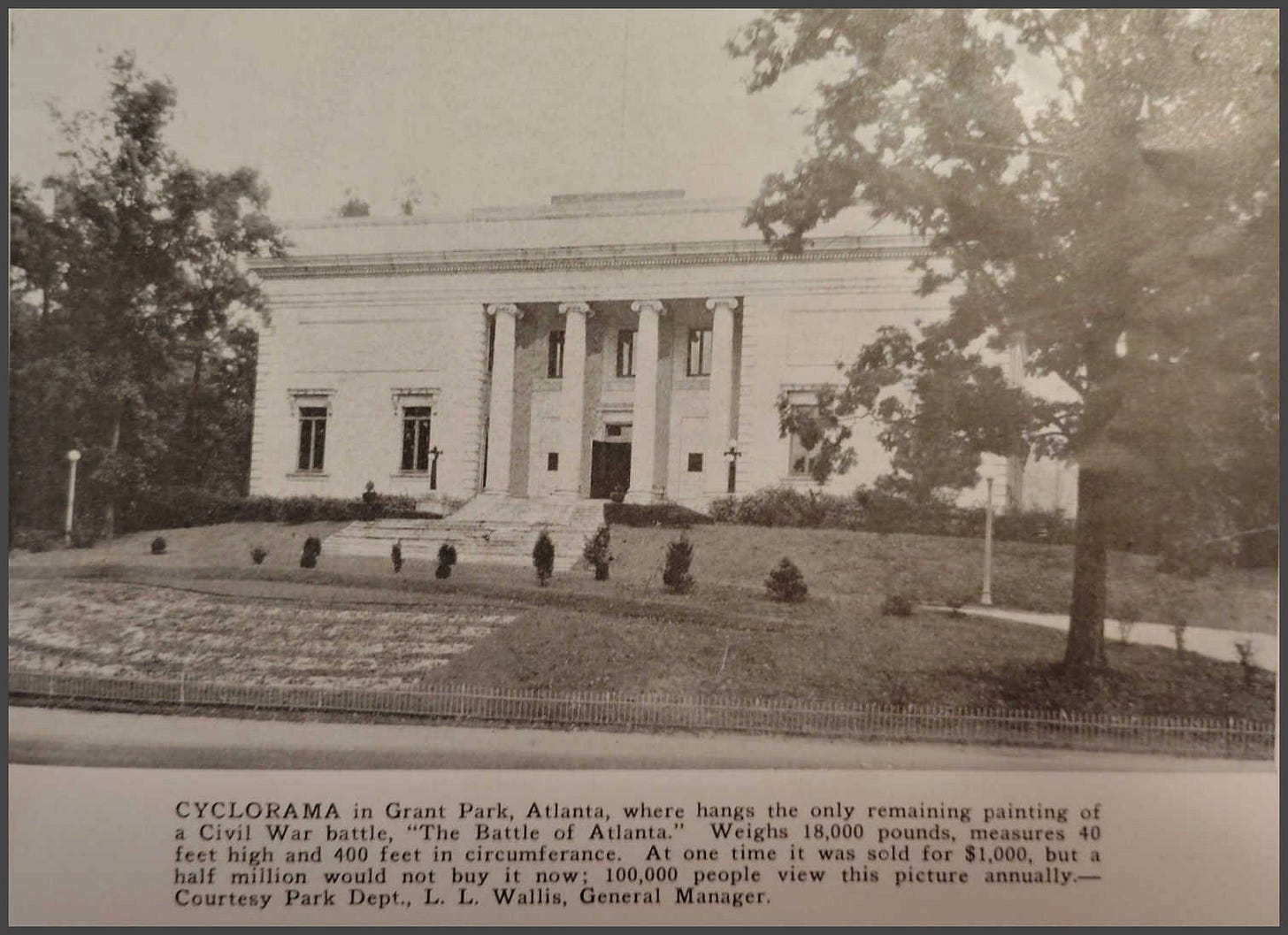

On July 22nd, the campaign's largest battle—the Battle of Atlanta—took place. The Federal army was closing in on the entrenchments of Atlanta and was now within two or three miles of the city. On the night of the 21st, General Blair, of McPherson’s army, had gained possession of a high hill on the left, which commanded a view of the heart of the city. Hood thereupon planned to recapture this hill, and make a general attack on the morning of the 22nd. He sent General Hardee on a long night march around the extreme flank of McPherson’s army, the attack to be made at daybreak. Meantime, General Cheatham, who had succeeded to the command of Hood’s former corps, were to engage Thomas and Schofield in front and thus prevent them from sending aid to McPherson.

Hardee experienced delays during his fifteen-mile march, resulting in an attack that commenced at noon. Around this time, General Sherman and McPherson were engaged in conversation near the Howard house, which served as the Federal headquarters, when they heard artillery fire emanating from beyond the hill recently secured by Blair. This signaled the beginning of the forthcoming battle. McPherson immediately mounted his horse and proceeded swiftly toward the source of the gunfire. Upon encountering Logan and Blair near the railroad, he briefly consulted with them before each officer proceeded to their respective positions along the battle line. McPherson dispatched aides and orderlies in multiple directions with messages, retaining only two by his side. He then rode into a forest and was suddenly confronted by a portion of the Confederate army under General Cheatham. “Surrender,” was the call that rang out. But he wheeled his horse as if to flee, when he was instantly mortally wounded, and the horse galloped back riderless.

The passing of James B. McPherson represented a significant loss for the Union army. At thirty-six, he was regarded as one of the nation's most capable leaders and had already achieved the position of department commander. McPherson was the only man in all the Western armies whom Grant, on going to the East, placed in the same military class with Sherman.

Logan assumed command following the previous leader's fall, as the battle continued with intensity. The Confederate forces advanced steadily, capturing multiple artillery pieces. Cheatham maintained pressure, delivering successive volleys into the Army of Tennessee, which began to show signs of division as a widening gap formed within its ranks. The Confederates were pouring through. Sherman was present and saw the danger. Calling for Schofield to send several batteries, he placed them and poured a concentrated artillery fire through the gap and mowed down the advancing men in swaths. At the same time, Logan pressed forward, and Schofield’s infantry was called up. The Confederates were hurled back at a great loss. The shadows of the night fell—the Battle of Atlanta was over. Hood’s losses exceeded eight thousand of his brave men, whom he could ill spare. Sherman lost about thirty-seven hundred.

The Confederate army recuperated within the defense of Atlanta—behind an almost impregnable barricade. Sherman had no hope of carrying the city by assault, while to surround and invest it was impossible with his number. He was determined to strike Hood’s line of supplies. On July 28th, Hood again sent Hardee out of his entrenchments to attack the army of Tennessee, now under the command of General Howard. A fierce battle at Erza Church on the west side of the city ensued, and again the Confederates were defeated with heavy loss.

A month passed and Sherman had made little progress toward capturing Atlanta. Two calvary raids which he organized resulted in defeat, but the two railroads from the south into Atlanta were considerably damaged. But, late in August, the Northern commander made his daring move that proved successful. Leaving his base of supplies, as Grant had done at Vicksburg, and marching towards Jonesboro, Sherman destroyed the Macon and Western Railroad, the only remaining line of supplies to the Confederate Army.

Hood attempted to block the march on Jonesboro, and Hardee was sent with his and S. D. Lee’s Corps to attack the Federals while he himself sought an opportunity to move upon Sherman’s right flank. Hardee’s attack failed, and this necessitated the evacuation of Atlanta. After blowing up his magazines and destroying the supplies which his men could not carry with them, Hood abandoned the city, and the next day, September 2nd, General Slocum, having succeeded Hooker, led the Twentieth Corps of the Federal army within its earthen walls. Hood had made his escape, saving his army from capture. His chief desire would have been to march directly north on Marietta and destroy the depots of Federal supplies, but a matter of more importance prevented. Thirty-four thousand Union prisoners were confined at Andersonville, and so a small body of calvary could have released them. So, Hood placed himself between Andersonville and Sherman.

In the early days of September, the Federal hosts occupied the city to which they had labored all summer long. At East Point, Atlanta, and Decatur, the three armies settled for a brief rest, while the cavalry stretched for many miles long the Chattahoochee, protecting their flanks and rear. Since May, their ranks had been depleted by some twenty-eight thousand killed and wounded, while nearly four thousand had fallen prisoners into the Confederate hands.

It was a great price, but whatever else the capture of Atlanta did, it insured the re-election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency of the United States. The total Confederate losses were in the vicinity of thirty-five thousand, of which thirteen thousand were captured as prisoners.

Almost after the capture of Atlanta, Sherman decided to remain there for some time and to make it a Federal military center and ordered all the inhabitants removed. General Hood pronounced the act one of ingenious cruelty, transcending any that had ever come to his notice in the dark history of the war. Sherman insisted that his act was one of kindness and the decision was fully carried out. Many of the people chose to go southward, others to the north, the latter being transported free, by Sherman’s order, as far as Chattanooga.

Shortly after the middle of September, Hood moved his army from Lovejoy’s Station, just south of Atlanta, to the vicinity of Macon, where Jefferson Davis visited the encampment, and on the 22nd made a speech to the homesick Army of Tennessee which, reported in the Southern newspapers, disclosed to Sherman the new plans of the Confederate leaders.

Hood, in the hope pf leading Sherman away from Atlanta, crossed the Chattahoochee on the 1st of October, destroyed the railroad above Marietta and sent General French against Allatoona. It was a brave defense of this place by General John M. Corse that brought forth Sherman’s famous message, “Hold out; relief is coming.” Corse had been ordered from Rome to Allatoona by signals from mountain to mountain, over the heads of the Confederate troops, who occupied the valley between. Reaching the mountain pass soon after midnight, on October 5th, Corse added a thousand men to the nine hundred already there, and soon after daylight the battle had begun. General French, in command of the Confederates, first summoned Corse to surrender, and receiving a defiant answer, opened fire.

During the battle, Sherman was positioned on Kennesaw Mountain, where he observed the smoke on the battlefield and heard the sound of cannon fire. Upon receiving a signal that Corse was present and in command, Sherman remarked on Corse's leadership by saying, “If Corse is there, he will hold out; I know the man,” and anticipated that he would continue to hold his position. Corse did maintain his post, reportedly with losses of around seven hundred men, including himself among the wounded, while French's forces sustained over one thousand casualties.

It was about this time that Sherman fully decided to march to the sea. Sometime before this he had telegraphed Grant: “Hood…can constantly break my roads. I would infinitely prefer to make a wreck of the road…send back all my wounded and worthless, and, with my effective army, move through Georgia, smashing things to the sea.” On October 11, Grant gave permission for the march, and on November 2nd, he telegraphed Sherman at Rome: “I do not really see that you can withdraw from where you are to follow Hood without giving up all we have gained in territory. I say, then, go as you purpose.”

Sherman moved his army back to Atlanta; sent the vast army store that he had collected at Atlanta, which he could not take with him, as well as his wounded, to Chattanooga, destroyed the railroad, also the machine shops at Rome, and on November 12th, deliberately cut himself off from all communications with the Northern states, by severing telegraph lines.

For the following two days, Atlanta experienced heightened activity and considerable movement. The great depot, roundhouse and machine shops were destroyed. Walls were battered down; chimneys pilled over; machinery smashed to pieces, and boilers punched full of holes. Heaps of smoldering rubbish covered the spots where fine buildings had stood, and on the night of November 15th, the torch was applied to every building and home in the Atlanta area.

Only the commanders of the wings and Kilpatrick were entrusted with the secrets of Sherman’s intentions. But even Sherman was not fully decided as to his objective—Savannah, Georgia or Port Royal, South Carolina, until well on the march.

Howard led his wing to Gordon by way of McDonough as if to threaten Macon, while Slocum proceeded to Covington and Madison, with Milledgeville as his goal. General Sherman accompanying first one corps of his army, then another,

The night of November 22nd, Sherman spent in the home of General Cobb, who had been a member of the United States Congress and of Buchanan’s Cabinet. Thousands of soldiers encamped that night on Cobb’s plantation, using his fences for campfire fuel. By Sherman’s order, everything on the plantation movable or destructible was carried away the next day or destroyed.

Overall, the great march was but little disturbed by the Confederates. The Georgia militia, probably ten thousand in all, did what they could to defend their homes and their families; but their endeavors were futile against the vast hosts that were sweeping through the country.

The great army kept on its way by various routes, leaving a swath of destruction, from forty to sixty miles wide in its wake. All public buildings that might have military use were burned, with a great number of private dwellings and barns, some by accident, others wantonly. This fertile and prosperous region, after the army had passed, was a scene of death, ruin, and desolation.

Day by day Sherman issued orders for the progress of the wings, but on December 2nd they contained the decisive words, “Savannah.” What a tempting prize this was for this fine Southern city, and how the Northern commander would add to his laurels could he effect its capture. The memories clinging about the historic old town, with its beautiful parks and its magnolia-lined streets, are part of the inheritance of not only the South, but all of America. Here Oglethorpe had bartered with the wild men of the forest, and here in the days of the Revolution, Count Pulaski and Sergeant Jasper had given up their lives in the cause of liberty.

Sherman had set his heart on capturing Savanna; but on December 15th, he received a letter from Grant which greatly disturbed him. Grant ordered him to leave his artillery and calvary, with infantry enough to support them, and with the remainder of his army to come by sea to Virginia and join forces before Richmond. Sherman prepared to obey but hoped that he would be able to capture the city before any of the transports would be ready to carry him northward.

Dear Monica,

Another great post!! Your thoroughness and attention to detail and to the sequencing of the pieces of the narrative is a true model of how to write. I hope you are doing well, and please keep up the great work.

Thank you. Excellent work and story telling ( of factual history)