The Blockade & The Rebel War Clerk's Diary

An opinion piece. Life during the blockade of ports.

A few days after his call for troops in 1861, Lincoln inaugurated the blockade, an essential part of the grand strategy of the war. If successfully instituted and maintained, this measure would inevitably strangle the Confederacy. Unable to sustain itself without exports and imports, it must eventually succumb.

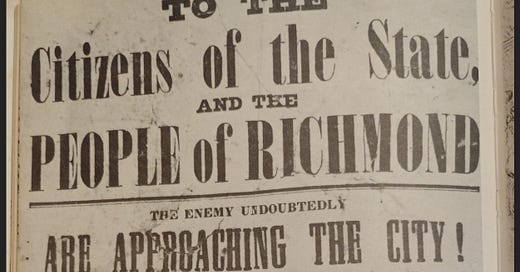

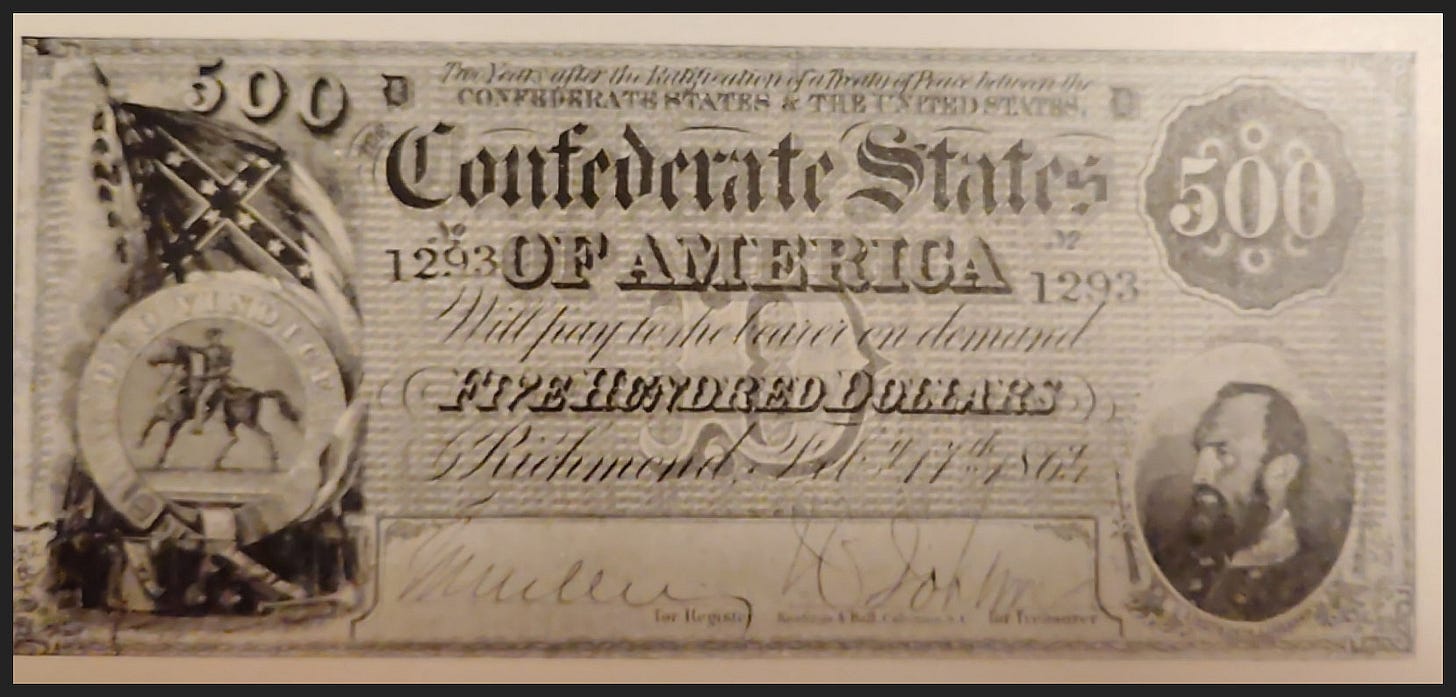

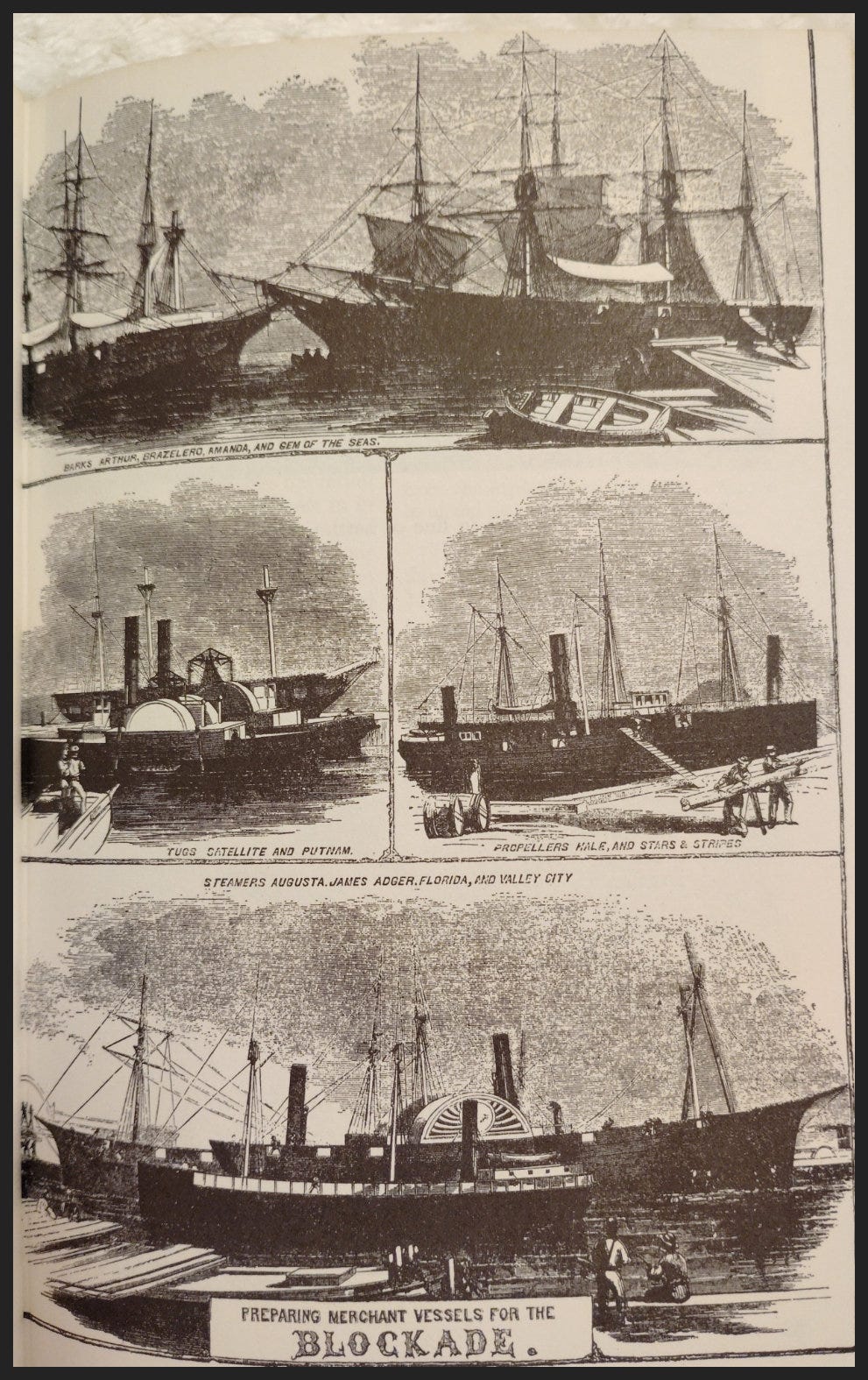

In a war whose successful termination depended on the exhaustion of the South, the blockade of the Southern ports constituted an important feature. At the beginning the successful blockade of a coast measuring more than three thousand miles seemed utterly out of reach and was not even calculated on by the South as a possible event; and, indeed, it seemed to require some miracle for a nation which, on the first of January, 1861, had but a single war steamer available for the defense of its entire Atlantic coast. But this aspect of the case was delusive. Lincoln promptly laid an embargo on the ports of the seven states then belonging to the Confederacy. This Proclamation 81 happened on April 19, 1861. On the twenty-seventh of April, he included within the limits of his proclamations the ports of Virginia and North Carolina.

A potent factor in sapping the foundations of Confederate hope and Confederate credit was the blockade. First held in contempt; later the fruitful mother of all errors as to the intentions of European powers; ever the growing constrictor whose coil was to crush out the South’s life. It became harder and harder each year. At first, Lincoln’s proclamation was laughed at in contempt in the South. The vast extent of the South Atlantic and Gulf coasts, pierced with innumerable safe harbors, seemed to defy any scheme for hermetic sealing. The limited Federal navy was powerless to do more than keep loose watch over ports of a few large cities, and if these were effectually closed, it was felt that new ones would open. Had the South made prompt and efficient use of opportunity and resources at hand when the blockades first started, by placing credits abroad and running in essential supplies, the result of the first year’s blockade might largely have nullified its effect for the last three. But the very inefficiency of the blockade at the onset lulled the South into a false security.

The South misjudged, until error proved fatal, the enterprise and grit of the Union character. So gradual were the appreciable results of this naval growth, so nearly imperceptible was the actual closing of Southern ports, that the masses of people realized no real evil until it had long been an accomplished fact.

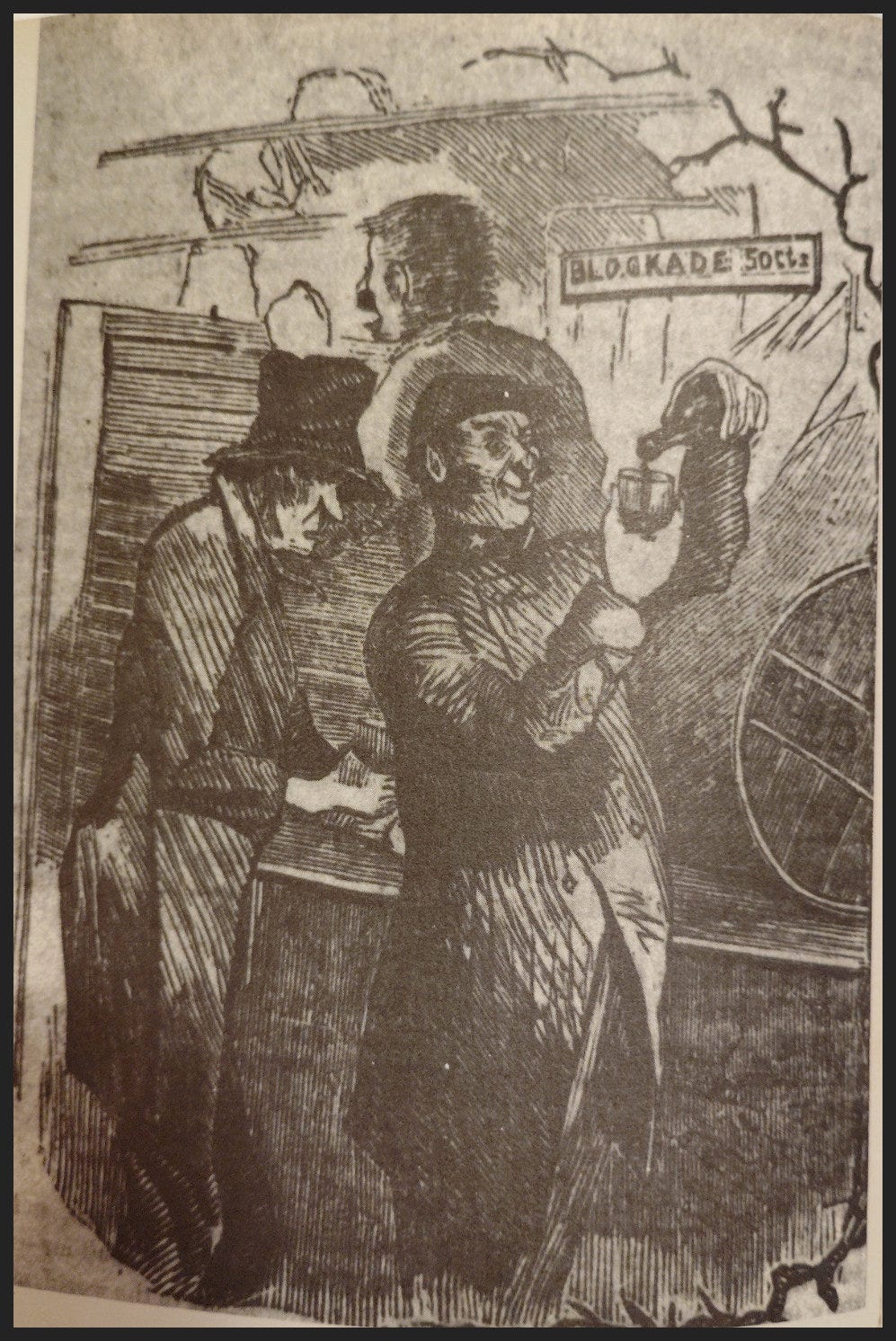

One reason why the result of the blockade, after it became actually effective, was not earlier realized in the South was that private speculation promptly utilized opportunities which the government had neglected. Private ventures, and even great companies formed for the purpose, made blockade breaking the royal to riches. Almost every conceivable article of merchandise came to Southern ports, often in quantities apparently sufficient to glut the market and almost always of inferior quality.

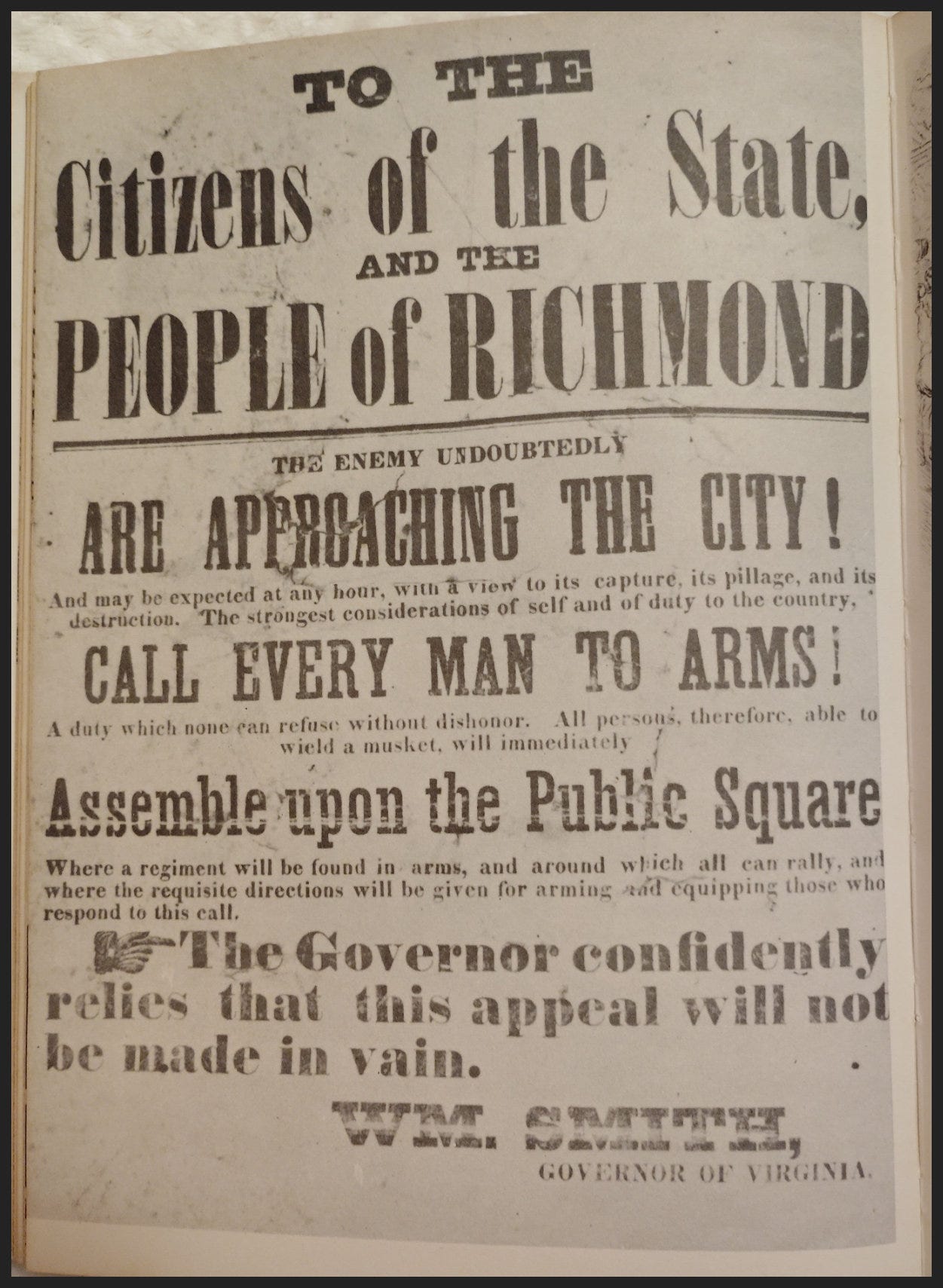

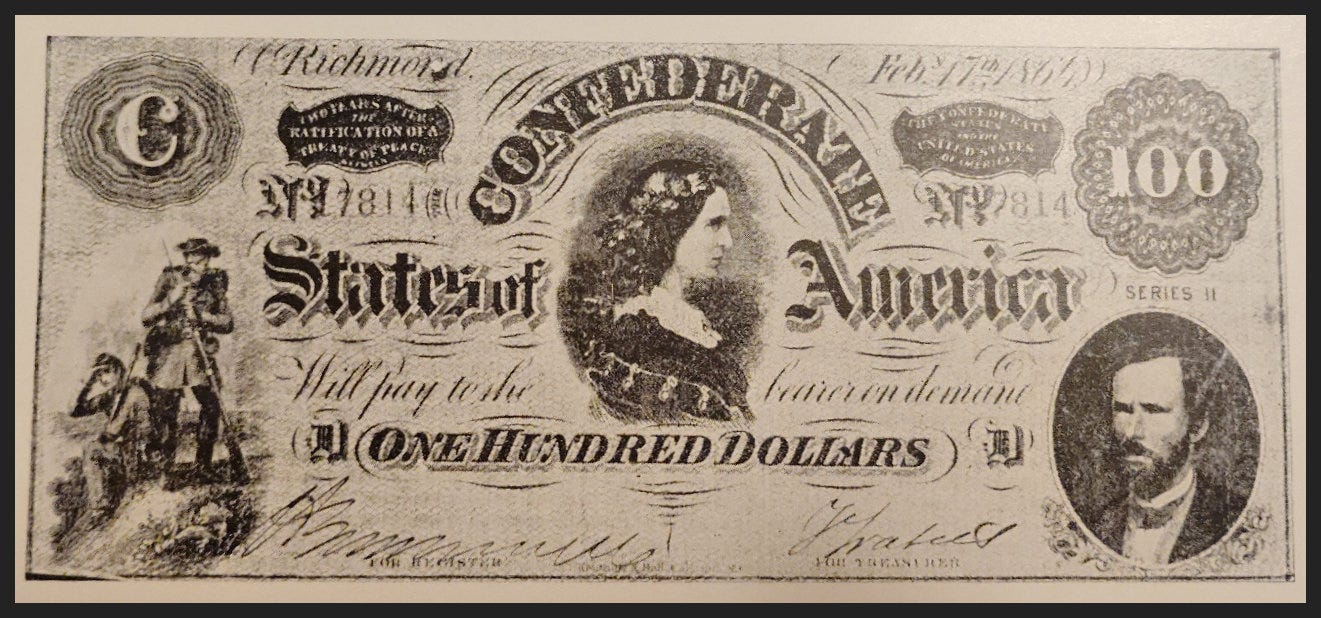

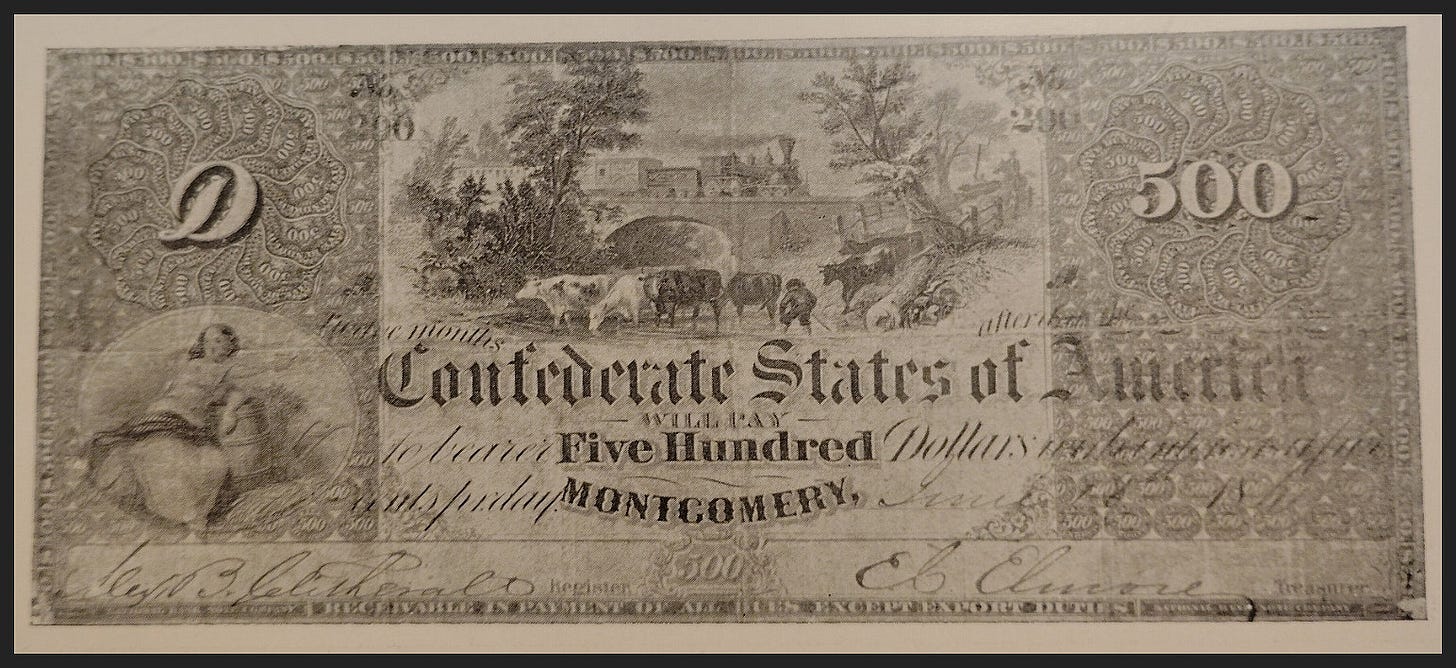

Earlier ventures were content with profits of 100 to 200 percent, but as the risk increased and Confederate money depreciated, it became not an unusual thing for successful investment to realize from 1,500 to 2,000 percent on its first cost.

Still, even this profit as against the average loss, perhaps two cargoes out of five, made the trade hazardous. Only a great capital source could supply the demand. Therefore, sprung the great blockade, breaking corporations like the Bee Company, Collie & Company, Fraser, and Trenholm & Company. With capital and credit unlimited, with branches at every point of purchase, with constantly growing orders from the departments, these giant concerns could control the market and make their own terms.

Their growing power soon became quasi dictation to the government itself; the national power was filtered through these alien arteries; and the South became the victim. Its treasury the mere catspaw, of the selfsame system, which clear sight and medium ability could so easily have been averted from the beginning.

So, why did the Confederacy lose the war? Historians are still questioning this engrossing question, and they are still unable to agree on the answer. There is a fairly general agreement, though, that the South did not lose the war on the battlefield. To be sure the Confederates were beaten at Vicksburg and Gettysburg, Chattanooga and Atlanta, decimated in the Wilderness, and shattered by Sherman’s march from Atlant to the sea and beyond. But these military defeats, so runs the argument, were consequences, not causes.

The most varied causes are assigned to explain these defeats; the blockade and shortages or essential materials; failure to win the foreign recognition so confidently anticipated; the breakdown of finance and of transportation; the incompetence of the President and of Congress; the disintegrating impact of State rights. Yet the Confederacy used such resources of manpower as it had, it might not have suffered defeat. There was food enough in the Confederacy; finances could have been controlled; the transportation system was not beyond repair, and foreign intervention would have followed upon military success and a statesmanlike policy toward such things as cotton and slavery; State rights denied to the Confederacy resources that promised victory; a wiser government would have made Lee commander in chief and permitted him to control the grand strategy of the war, and so on and so forth. So, the argument runs, and most who question fall back, in the end, on the vague phrase “breakdown of morale” a phrase which merely asks the question.

But what and this adds up to is that the Confederate cause was lost in the Confederacy itself—that is, behind the lines. The internal history of the Confederacy thus becomes a matter of paramount interest. The following opinion is not designed, primarily, to illuminate the breakdown of the Confederacy, but there can be little doubt that it does so. Successive excerpts describe the inadequacy of food and other necessities, runaway inflation, the incompetence of medical services and lack of medication, the short-sighted cotton policy, the effectiveness of the blockade, in impact of invasion and the defeat on morale, dissatisfaction with the conduct of the war, the role of State rights, and the growth of defeatism.

Concentration on staple crops at the expense of grains and dairy products made the agriculture South far from self-sufficient, while industrially the South was almost wholly dependent on the North or Britian. These basic economic factors, plus state competition for such as food supply and industrial products as could be found, contributed largely to the growing shortages that harassed the Confederacy.

After the war was fairly under way, the Confederate government tried to meet nearly all its expenses by issues of paper money. This money steadily depreciated in value, so that every new issue was followed by a rise in prices which had to be met, in turn, by another new issue. By the end of 1864, the paper currency in circulation had reached about one billion dollars.

Other factors, too, contributed to inflation: the blockade by shutting off imports from abroad; the breakdown of the transportation system by making it hard to move merchandise; the decline in farm and factory production. All this meant that prices soared, the wages, especially the sorry wages of the soldiers, became almost worthless, and that the poor everywhere and even the city folk suffered devastating hardships.

The deprivations of war exacted a profound toll on families in both the cities and the countryside. Although many were willing to tolerate inconveniences early in the war, growing disaffection with the Southern cause spurred resistance. Food riots were not uncommon in cities. Women who could not find enough food to feed their families took to the streets. In rural sections of the South, the conscription of white men into the army and impressment of slaves caused a wide range of problems and tensions. In large plantations, white women often feared the departure of so many men which made them vulnerable to slave violence and rebellions. Women living near Bern, North Carolina, petitioned the Governor to exempt the remaining men still at home from serving in the army.

“We pray your Excellency to consider that in the absence of all protection the female portion of this community may be subjected to a system of outrage that may be justly denominated the harrow of harrows more terrible to the contemplation of the virtuous maiden and matron than death,” read the petition to Governor Zebulon Vance.

In other parts of the South, small farmers objected to policies that favored plantation counties. Forty-six men in Randolph County in eastern Alabama petitioned President Jefferson to relieve the impoverished yeomen from government demands that were literally starving people to death.

John Beauchamp Jones, whose Rebel War Clerk’s Diary which I will use in this post, was an editor and novelist who obtained a clerkship in the War Department for the express purpose of being at the center of things and writing about them. His book, verbose and prejudiced, is an authentic record of the day-by-day life in the capital city of Richmond.

A War Clerk Suffers Scarcities in Richmond

May 23, 1862. —Oh, the extortioners! Meats of all kinds are selling at fifty cents per pound; butter, seventy-five cents; coffee, a dollar and half; tea, ten dollars; boots, thirty dollars per pair; shoes, eighteen dollars; ladies’ shoes, fifteen dollars; shirts, six dollars each. Houses that were rented for five hundred dollars last year are a thousand dollars now. Boarding, from thirty to forty dollars per month. General Winder has issued an order fixing the maximum prices of certain articles of marketing, which has only the effort of keeping a great many things out of the market. The farmers have to pay the merchants and Jews their extortionate prices and complain very justly of the partiality of the general. It does more harm than good.

October 1st. —How shall we subsist this winter? There is not a supply of wood or coal in the city—and it is said that there are not adequate means of transporting it hither. Flour at sixteen dollars per barrel and bacon at seventy-five cents per pound threatens a famine. And yet, there are no beggars in the streets. We must get a million more men in arms and drive the invader from our soil. We are capable of it, and we must do it. Better die in battle than die of starvation produced by the enemy.

The newspapers are printed on half-sheets—and I think the publishers make money; the extras (published almost every day) are sold to the newsboys for ten cents and often sold by them for twenty-five cents. These are mere slips of paper, seldom containing more than a column—which is reproduced in the next issue. The matter of the extras is mostly made up from the Northern papers, brought hither by persons running the blockade. The supply is pretty regular, and dates are rarely more than three or four days behind the time of reception. We often get the first accounts of battles at a distance in this way, as our generals and our government are famed for prudential reticence.

6th. –This evening Curtis and I expect the arrival of my family from Raleigh, N. C. We have procured for them one pound of sugar, eighty cents; four loaves of bread, as large as my fist, twenty-five cents each; and we have a little coffee, which is selling at two dollars and a half per pound. In the morning someone must go to market, or else there will be short commons. Washing is two dollars and a half per dozen pieces. Common soap is worth seventy-five cents per pound.

November 7th. —Yesterday I received from the great agent of the City Councils fourteen pounds of salt, having seven persons in my family, including the servant. One pound to each member, per month, is allowed at five cents a pound. The extortionists sell it at seventy cents per pound. One of them was drawing for his family. He confessed it but said he paid fifty cents for the salt he sold at seventy cents. Profit ten dollars per bushel! I sent in an article today to the Enquirer, suggesting that fuel, bread, meat, etc. be furnished in the same manner. We shall soon be in a state of siege.

21st. —Common shirting cotton and Yankee calico that used to sell at twelve and a half cents per yard in now a dollar seventy-five! What a temptation for the Northern manufacturers! What a rush of trade there would be if peace should occur suddenly! And what a party there would be in the South for peace (and unity with Northern Democrats) if the war raged somewhat differently. The excesses of the Republicans compel our people to be almost a unit. This is all the better for us. Still, we are in quite a bad way now, God knows!

Mr. Dargan, M.C., write to the President from Mobile that the inhabitants of that city are in awful conditions—meal is selling for three dollars and a half per bushel and wood at fifteen dollars a cord—and that the people are afraid to bring supplies, apprehending that the government agents will seize them. The President (thanks to him!) had ordered that interference with domestic trade must not be permitted.

December 1st. —God speed the day of peace! Our patriotism is mainly in the army and among the ladies of the South. The avarice and cupidity of the men at home, could only be excelled by the ravenous wolves; and most of our sufferings are fully deserved. Where people will not have mercy on one another, how can they expect mercy? The depreciate the Confederate notes by charging from $20 to $40 per bushel for flour; $3.50 per bushel of meal; $2 per lb. for butter; $20 per cord of wood, etc. When we have peace let the extortionists be remembered! Let an indelible stigma be branded upon them!

A portion of the people look like vagabonds. We see men and women and children in the streets in dingy and dilapidated clothes; and some are gaunt and pale with hunger—the speculators, and thieving quartermasters and commissaries only, looking sleek and comfortable. If this stage of things continues a year or longer, they will have their reward. There will be government bankruptcy, and all their gains will turn to dust and ashes, dust and ashes!

January 18th, 1863. —We are now, in effect, in a state of a siege, and none but the opulent, often those who have defrauded the government, can obtain a sufficiency of food and raiment. Calico, which could once be bought for twelve and a half cents per yard, is now selling for two dollars and a quarter, and a lady’s dress of calico costs her about thirty dollars. Bonnets are not to be had. Common bleached cotton shirting brings a dollar and a half per yard. All other dry goods are held in the same proportion. Common tallow candles are a dollar and a quarter pound of soap, one dollar; hams, one dollar; opossum, three dollars; turkeys, four to eleven dollars; sugar, brown, one dollar; molasses, eight dollars per gallon; potatoes, six dollars per bushel, etc. These evils might be remedied by the government, for there is no great scarcity of any of the substantial’s and necessities of life in the country, if they were only distributed. The difficulty in procuring transportation, and the government monopolizes the railroads and canals.

February 11th. —Some idea may be formed of the scarcity of food in this city from the fact that, while my youngest daughter was in the kitchen today, a young rat came out of its hole and seemed to beg for something to eat; she held out some bread, which it ate from her hand, and seemed grateful. Several others soon appeared and were tame as kittens. Perhaps we shall have to eat them!

18th. —One or two of the regiments of General Lee’s army were in the city last night. The men were pale and haggard. They have but a quarter of a pound of meat per day. But meat has been ordered from Atlanta. I hope it is abundant there.

All the necessities of life in the city are still going up in price. Butter, three dollars a pound; beef, one dollar; bacon, a dollar and a quarter; sausage meat, one dollar; and even liver is selling at fifty cents per pound. By degrees, quite perceptibly, we are approaching the condition of famine. What effect will this produce on the community is to be seen. The army must be fed or disbanded, or else the city must be abandoned. How we, the people,” are to live is a thought of serious concern.

March 30th. —The gaunt from wretched famine still approaches with rapid strides. Meal is now selling at twelve dollars per bushel and potatoes at sixteen. Meats have almost disappeared from the market, and none but the opulent can afford to pay three and a half dollars per pound for butter. Greens, however, of various kinds, are coming in; and as the season advances, we may expect a diminution of prices. It is strange that on the 30th of March, even in the “sunny South,” the fruit trees are as bare of blossoms and foliage as at mid-winter. We shall have a fire until the middle of May—six months of winter! I am spading up my garden and hope to raise a few vegetables to eke out a miserable subsistence for my family.

April 17th. —Pins are so scarce and costly that it is now a pretty general practice to stoop down and pick up any that is found in the street. The boarding houses are breaking up, and rooms, furnished or unfurnished, are renting out to messes. One dollar and fifty cents for beef leaves no margin for profit even at one hundred dollars per month, which is charged for board, and most of the boarders cannot afford to pay that price. Therefore, they can take rooms and buy their own scant food. I am inclined to think provisions would not be deficient to an alarming extent if they were equally distributed. Wood is no scarcer than before the war, and yet thirty dollars per load (less than a cord) is demanded for it and obtained.

August 22nd. —Night before last all the clerks in the city post-office resigned, because the government did not give them salaries sufficient to subsist them. As yet their places have not been filled, and the government gets no letters—some of which lying in the office may be of importance as to involve the safety or ruin of the government. Tomorrow is Sunday, and of course the mails will not be attended to before Monday—the letters lying here four days unopened! This looks as if we had no Postmaster General.

October 22nd. —A poor woman yesterday applied to a merchant on Carey Street to purchase a barrel of flour. The price he demanded was $70.

“My God!” exclaimed she, “how can I pay such prices? I have seven children; what shall I do?”

“I don’t know, madam,” he said cooly, ‘unless you eat your children.”

Such is the power of cupidity—it transforms men into demons. And if this spirit prevails throughout the country, a just God will bring calamities upon the land, which will teach these cormorants, but which, it may be feared, will involve all classes in a common ruin.

January 26, 1864. —The prisoners on Belle Isle (8,000) have had no meat for eleven days. The Secretary says the Commissary General informs him that they fare as well as our armies, and so he refused the commissary (Capt. Warner) of the prisoners a permit to buy and bring to the city cattle he might be able to find. An outbreak of the prisoners is apprehended: and if they were to rise, it is feared some of the inhabitants of the city may join them, for they, too, have no meat—many of them—or bread either. They believe the famine is owing to the imbecility, or worse of the government. A riot would be a dangerous occurrence now: the city battalion would not fire on the people—and if they did the army might break up and avenge their slaughtered kindred. It is a perilous time.

March 18th. —My daughter’s cat is staggering day-to-day, for want of any animal food. Sometimes I fancy I stagger myself. We do not average two ounces of meat daily; and some do not get any for several days altogether. Meal is $50 per bushel. I saw adamantine candles sell at auction today (box) at $10 per pound; tallow, $6.50. Bacon brought $7.75 per pound by the 100 pounds.

April 8th. —Bright and warm—really a fine spring day. It is the day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer, and all the offices are closed. May God put into the hearts of the extortioners to relent, and abolish, for a season, the insatiable greed for gain! I paid $25 for a half a cord of wood today, new currency. I fear a nation of extortioners are unworthy of independence, and that we must be chastened and purified before success will have vouchsafed us. What enormous appetites we have now, and how little illness, since food had become so high in price! I cannot afford to have more than one ounce of meat daily for each member of my family of six; and today Curtis’s parrot, which has accompanied the family in all their flights, and, it seems, will never die, stole the cook’s ounce of fat meant and gobbled it up before it could be taken from him. He is permitted to sit at one corner of the table and has lately acquired a fondness for meat. The old cat goes staggering about from about from debility, although Fannie offers him her share. We see neither rats nor mice about the premises now. This is famine. Even the pigeons watch the crusts in the hands of children and follow them in the yard. And, still, there are no beggars.

August 13th. —Flour is falling: It is now $200 per barrel—$500 a few weeks ago; and bacon is falling in price also, from $11 to $6 per pound. A commission merchant said to me, yesterday, that there was at least eighteen months’ supply (for the people) of breadstuffs and meats in the city; and pointing to the upper windows at the corner of Thirteenth and Cary Streets, he revealed the ends of many barrels piled above the windows. He said that flour has been there two years, held for “still higher prices.” Such is the avarice of man. Such is war. And such the greed of extortioners, even in the midst of famine—and famine in the midst of plenty! —Jones, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary

Parthenia Hague Tells How Women Outwitted the Blockade

Probably not until 1863 was the blockade really effective, but even well before that date the South began to feel the pinch for ordinary domestic necessities. Now the South was paying the price of neglecting to develop even local industries. Probably one of the best accounts of what life was like for a Southern family from day to day, was that by Parthenia Hague, a Georgia lady who went to live on an Alabama plantation during the war. The following are excerpts from A Blockaded Family, by Parthenia Hague

The obtaining of salt became extremely difficult when the war had cut off our supply. This was especially true in regions remote from the seacoast and border States, such as the interior of Alabama and Georgia. Here again we were obligated to have recourse to whatever expedient ingenuity suggested. All the brine left in troughs and barrels, where pork had been salted down, was carefully dipped up, boiled down, and converted into salt again. In some cases, the salty soil under old smokehouses was dug up and placed in hoppers, which resembled backwoods ash-hoppers, made from leaching ashes is the process of soap-manufacture. Water was then poured upon the soil, the brine which percolated through the hopper was boiled down to the proper point, poured into vessels, and set in the sun, which by evaporation completed the rude process. Though never of immaculate whiteness, the salt which resulted from these methods served well enough for all our purposes, and we accepted it without complaining.

Before the war there were in the South but a few cotton mills. These were kept running night and day, as soon as the Confederate army was organized, and we were ourselves prevented by the blockade from purchasing clothing from the factories at the North, or clothing from France or England. The cotton which grew in the immediate vicinity of the mills, kept them well supplied with raw material. Yet notwithstanding the great push of the cotton mills, they proved totally inadequate, after the war began, to our vast need of clothing of every kind. Every household now became a miniature factory in itself, with its cotton, cards, spinning wheel and the clang of batten of the loom was borne on the ear.

That the slave might be well clad, the owners kept, according to the number of slaves owned, a number of Negro women carding and spinning, and had looms running all the time. Now and then a planter would be so fortunate as to secure a bale or more of white sheeting and osnaburgs from the cotton mills, in exchange for farm products, which would be quite a lift, and give a little breathing spell from the almost incessant whirr, hum, and clang of the spinning wheel and loom…

One of our most difficult tasks was to find a good substitute for coffee. This palatable drink, if not a real necessity of life, is almost indispensable to the enjoyment of a good meal, and some Southerners took it three times a day. Coffee soon rose to thirty dollars per pound; from that it went to sixty and seventy dollars per pound. (good workmen received thirty dollars per day; so it took two days of hard labor to buy one pound of coffee, and scarcely any could be had even at that fabulous price…

There were those who planted long rows of the okra plant on the borders of their cotton or corn fields and cultivated this with the corn and cotton. The seeds of this, when mature and nicely browned, came nearer in flavor to the real coffee that any other substitute I now remember. Yam potatoes used to be peeled, sliced thin, cut into small squares, dried and then parched brown; they were thought to be the next best to okra for coffee. Browned wheat, meal, and burnt corn made passable beverages; even meal-bran was browned and used for coffee if other substitutes were not obtainable. —Hague, A Blockaded Family

The Confederates Burn Their Cotton

Two considerations persuaded the Confederacy to try to limit cotton production: the necessity of growing enough food for her needs, and the desire to create an artificial cotton scarcity for purposes of bargaining for foreign recognition. The result of the Confederate and state laws, the latter by all odds and the most effective, and of invasion and the general derangement of war was a reduction in the cotton crop from over four million bales in 1861 to only three hundred thousand bales in 1864. In addition to this reduction of planting, the Confederate Congress required owners to destroy all cotton that might fall into enemy hands, and it has been estimated that some two and a half million bales were destroyed by planters or by the Confederate armies. When Farragut forced the entrance to the Mississippi on April 24, 1862, the Confederates destroyed the cotton piled up in New Orleans to prevent it from falling into Federal hands.

Sarah Dawson was the daughter of Judge Thomas Gibbes Morgan, whose home in Baton Rouge was sacked by the Federal in 1862. She describes what it was like to see the cotton burning from her book, A Confederates Girl’s Diary.

April 26, 1862. —We went this morning to see the cotton burning, a sight never before witnesses and probably never again to be seen. Wagons, drays, everything that can be driven or rolled were loaded with the bales and taken a few squares back to burn on the commons. Negroes were running around, cutting them open, piling them up, and setting them afire. All were busy as though their salvation depended on disappointing the Yankees. Later, Charlie sent for us to come to the river and see him fire a flatboat loaded with the precious material for which the Yankees are risking their bodies and souls. Up and down the levee, as far as we could see, Negroes were rolling it down to the brink of the river where they would set the bales afire and push them in to float burning down the tide. Each sent up its wreath of smoke and looked like a tiny steamer puffing away. Only I doubt that from the source to be the mouth of the river there are as many boats afloat on the Mississippi. The flat-boat was piled with as many bales as it could hold without sinking. Most of them were cut open, while Negroes staved in the heads of the barrels of alcohol, whiskey, etc., and dashed bucketfuls over the cotton, to burn more quickly. There, piled the length of the whole levee or burning in the river, lay the work of thousands of Negroes for more than a year past. It had come from every side. Men stood by who owned the cotton that was burning or waiting to burn. They either helped or looked on cheerfully. Charlie owned but sixteen bales—a matter of some fifteen hundred dollars, but he was the head man of the whole affair and burned his own as well as the property of others.

A single barrel of whiskey that was thrown on the cotton cost the man who gave it one hundred and twenty-five dollars. (It shows what a nation in earnest is capable of doing.) Only two men got on the flatboat with Charlie when it was ready. It was towed up to the middle of the river, set afire in every place, then they jumped into the little skiff fastened in front and rowed to land. The cotton floated down the Mississippi in one sheet of living flame, even in the sunlight. It would have been grand at night. But then we will have fun watching it this evening anyway, for they cannot get through today, though no time is to be lost. Hundreds of bales remained untouched. An incredible amount of property has been destroyed today, but no one begrudges it. Every grogshop has been emptied, and gutter and pavements are floating with liquors of all kinds. So that if the Yankees are fond of strong drink, they will fare ill. –Dawson, A Confederate Girl’s Diary

What this post adds up to is that the blockade was a decisive factor in Union victory. We cannot say that without it the Confederacy would have won, but it’s clear that without it the war would have been greatly prolonged and might have ended in a stalemate. It must be kept in mind that Confederate susceptibility to the blockade need not have been as injurious as it actually was. First, the Confederacy was unprepared to take advantage of the feebleness of the blockade in 1861; as the Confederates did not anticipate a long war and there was no long-range buying program. Second, the blockade sent prices skyrocketing, and the Confederacy was unable to buy all that it might have obtained had it taxed more successfully or controlled prices or raised money abroad. Third, blockade running was largely a private enterprise, and shipowners imported luxuries rather than war essentials. Not until 1864 did the government assume control over it, requiring that every blockade-runner have a permit and allot at least one half of its cargo space to military essentials. Fourth, imports through Mexico and Texas were large, Galveston for example, remained in Confederate hands, but the Federal victories on the Mississippi nullified this immense advantage.

Proclamation 81, declaring a blockade of ports in rebellious states.

April 19, 1861

By the President of the United States of America

A ProclamationWhereas an insurrection against the Government of the United States has broken out in the States of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, and the laws of the United States for the collection of the revenue can not be effectually executed therein conformably to that provision of the Constitution which requires duties to be uniform throughout the United States; and

Whereas a combination of persons engaged in such insurrection have threatened to grant pretended letters of marque to authorize the bearers thereof to commit assaults on the lives, vessels, and property of good citizens of the country lawfully engaged in commerce on the high seas and in waters of the United States; and

Whereas an Executive proclamation has been already issued requiring the persons engaged in these disorderly proceedings to desist therefrom, calling out a militia force for the purpose of repressing the same, and convening Congress in extraordinary session to deliberate and determine thereon:

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, with a view to the same purposes before mentioned and to the protection of the public peace and the lives and property of quiet and orderly citizens pursuing their lawful occupations until Congress shall have assembled and deliberated on the said unlawful proceedings or until the same shall have ceased, have further deemed it advisable to set on foot a blockade of the ports within the States aforesaid, in pursuance of the laws of the United States and of the law of nations in such case provided. For this purpose a competent force will be posted so as to prevent entrance and exit of vessels from the ports aforesaid. If, therefore, with a view to violate such blockade, a vessel shall approach or shall attempt to leave either of the said ports, she will be duly warned by the commander of one of the blockading vessels, who will indorse on her register the fact and date of such warning, and if the same vessel shall again attempt to enter or leave the blockaded port she will be captured and sent to the nearest convenient port for such proceedings against her and her cargo as prize as may be deemed advisable.

And I hereby proclaim and declare that if any person, under the pretended authority of the said States or under any other pretense, shall molest a vessel of the United States or the persons or cargo on board of her, such person will be held amenable to the laws of the United States for the prevention and punishment of piracy.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this 19th day of April, A.D. 1861, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-fifth.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

By the President:

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State

Russian and the North did collaborate. Their boats posted off the coasts of New York and California, likely navigating the coasts. Some argue it was mutual to the emancipation and enlightenment of their respective nations. Others say it was a ploy by the Russians, laying in wait to secure resources towards fending off a Polish revolt.

Thanks Monica. Excellent,You have done it again! Keep it up! One side note I’ve run across in my unrelated research is that the Royal family of Russia sent ships to patrol the South’s coastline to further harass and destroy the South.