The Hanging of Mary Surrat Part 2

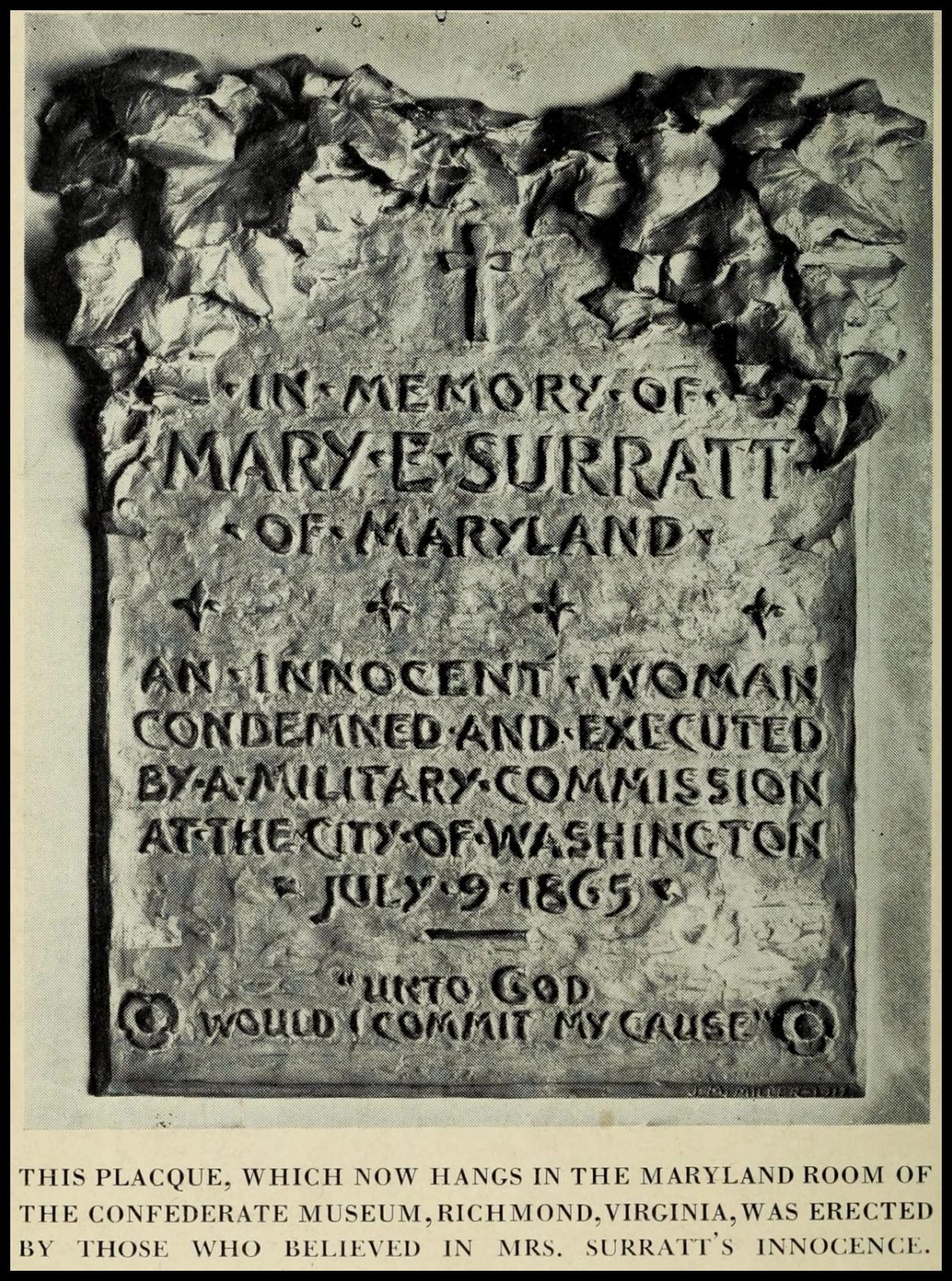

No cause justifies the death of innocent people.

“The souls of the just are in the hands of God, and the torment of malice shall not touch them. In the sight of the unwise they seem to die, but they are at peace.”

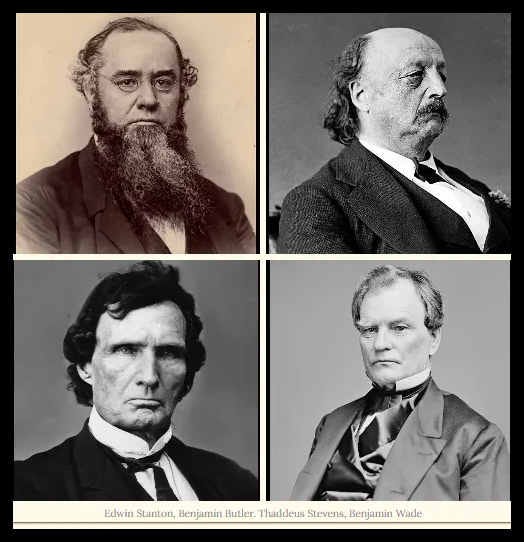

On May 1, 1865, President Andrew Johnson, with the encouragement of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and other members of the Radical Republican clique, announced that the Military Commission would try the Lincon assassination conspirators. There was an immediate outcry from a minority in Congress and the Administration over this unconstitutional order. The Constitution does not permit military courts to try civilians when civilian courts are in operation. The rules of evidence are much less rigorous in a military court: the rights of the accused are much abbreviated, and the court is a law unto itself of no appeals in its rulings, except for the President of the United States. The protests shocked Congressmen, former Attorney General Edward Bates, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and countless other attorneys were ignored, and on May 9, the Military Commission met for the first time.

Secretary Stanton appointed Major General David Hunter as President of the Court and Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt to act in a role that was somewhere between judge and prosecutor, most frequently the latter. But Stanton would take a keen day-by-day interest in the trial and an intense interest in its outcome. In the end, the cry for blood was louder than the cry for justice, and politics outweighed it all.

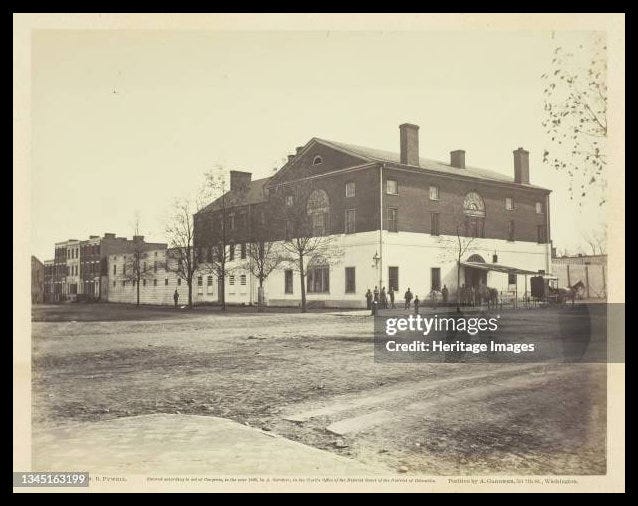

The Military Commission trial of the alleged conspirators in the Lincoln assassination convened on May 9, 1865. Court was held in a 30-foot-by-25-foot room at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary in Washington, near the cells of the accused. The weather was hot and humid, and the ventilation of the makeshift courtroom was poor. This frequently challenged the span of the military tribunal. The prisoners sat behind their defense attorneys on seats raised about one foot higher. The hoods of the male prisoners had been removed, but they were not allowed to speak, except to their defense attorneys, or to move. Their restricted movement made it difficult to get the attention of their attorneys. Despite their restrictions, defendant Lewis Powell managed to shout once that Mrs. Surratt was innocent. On several occasions, the press and a limited number of observers were allowed to attend the sessions. Mary Surratt was the center of public attention. Many of the observers indulged in conversations heaping humiliating verbal abuse on her throughout the hearing.

Booth’s diary, recovered from his body in Virginia, clearly indicated that up to and including April 13, 1865, the conspiracy was not to assassinate Lincoln, but to abduct him and hold him as a bargaining chip force a prisoner of war exchange or even to end the war, This extremely important evidence was withheld from the court and kept secret by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Although the abduction plan became known to the Military Commission, the prosecution and Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt continually tried to conflate the abduction plot with the assassination plot. Booth did not decide to attempt Lincoln’s assassination until late in the afternoon on April 14. He did not organize it until 8:00 p.m. that night, only two and a quarter hours before he shot Lincoln at the Ford’s Theatre.

It should also be noted that the U. S. War Department had refused to exchange prisoners since July 1863. Their objective was to deny the already badly outnumbered Confederate Army any source of desperately needed replacements. Consequently, however, POWs on both sides were suffering. Hence there was a humanitarian factor associated with the abduction plot. The main thrust of the prosecution in the case of Mary Surratt was to show that she was an active participant in the assassination plot. Thus, they tried hard to convince the Military Commission and attending reporters that she coordinated with Booth by making sure guns were ready for the assassins as they escaped through Surrattsville.

John Lloyd, her Surrattsville renter, gave perjured, but rather equivocal, testimony to that effect for the prosecution. Mrs. Surratt’s boarder Louis Weichmann was more indirect in his insinuations, but his testimony, formed under great duress, was damaging.

Just after the trial, but a few days before the executions on July 7, Louis Weichmann went for a walk with two friends: John Brophy and Louis Carland. Saying that his conscience was troubling him, Weichmann told them that he had been arrested as one of the conspirators, and that both Stanton and Col. H. L. Burnett had threatened him with death unless he revealed all about the assassination. He then admitted that he had lied on the witness stand to save his own life and keep his government position. Weichmann said that he wanted to go to St. Aloysius Church and make a confession, but he would not, as suggested by Carland, to make a statement under oath for fear of being indicted for perjury. On the day of the execution, John Brophy swore out a declaration of facts disclosing Weichmann’s statements and copied the Washington Constitutional Union. Brophy took the affidavit to the White House and sent it to President Andrew Johnson. He was told that Johnson thought it was “wholly without weight.” Carland also testified to Weichmann’s confession to them at the trial of John Surratt in 1867.

Weichmann later confided to John T. Ford, the owner of Ford’s Theater, that he had been subject to great duress by Secretary Stanton, Col. H. L. Burnett, and their detectives to change a testimony favorable to Mrs. Surratt to one that more suited Stanton. Wiechmann was then brought before Stanton, who expressed in a very intimidating manner that Weichmann was as guilty of the President’s death as Booth. In order to impress upon Weichmann further, the Secretary placed a rope around Weichmann’s neck. Stanton told him that if he didn’t testify as the government wished, he (Weichmann) would be hanged.

Other testimonies indicate that Weichmann was threatened with hanging more than once by the War Department officials and detectives. On May 5, Weichmann wrote this to Col. Burnett from Carroll Prison:

“You confused and terrified me so much yesterday that I was almost unable to say anything.”

Naturally, this note was not made available at the conspiracy trial. According to John Chandler Griffin’s (2006) book, Abraham Lincoln’s Execution, shortly after Weichmann’s initial arrest as a conspirator, he was thrown in a cell where a rope was tossed over a rafter and a noose looped on his neck. He was then threatened with immediate hanging, if he did not tell them what they wanted to know, and that his death would be reported as a suicide.

Also, according to John T. Ford, John Lloyd told him that he had agreed to testify against Mrs. Surratt only after he suffered extreme duress in the hands of his captors. After Lloyd was arrested in Surrattsville on April 18, he was taken to Bryantown to be examined by Col. H. H. Wells. When Lloyd refused to say anything against Mrs. Surratt, he was then hanged by his thumbs until he could no longer stand the pain. Only then, to spare himself from any further torture, did he agree to give perjured testimony against his landlady.

1n 1878, a written statement was presumably made by George Atzerodt was found in the papers of General W. E. Doster, Defense Attorney for both Atzerodt and Lewis Powell. This statement, dated the evening of May 1, 1865, was given to Provost Marshall McPhail in the presence of Detective John L. Smith. In that rambling document, Atzerodt made two conflicting statements. First, he said that Booth told him, “Mrs. Surratt went to Surrattsville to get out the guns which has been taken to that place by David Herold. This was Friday.” Then a little father on he stated, “Booth never said until the last night (Friday) that he intended to kill the President.”

In fact, Booth did not yet know that the President would be attending the play at Ford’s Theatre that night, when he spoke to Mrs. Surratt just before she and Weichmann left for Surrattsville.

Atzerodt’s statement was not used by the prosecution, probably because of the revealing contradiction. Perhaps Atzerodt, desperate to save his own life, was promised leniency if he could reinforce the prosecution’s attempt to connect Mrs. Surratt with arranging for the guns to be in place along the escape route. Undoubtedly, like Weichmann and Lloyd, Atzerodt failed to mention Booth assigning him to kill Vice President Johnson, but it is also evident from various testimonies and his actions that Atzerodt had no intention of carrying out Booth’s orders.

Secretary Stanton’s Chief Detective, Col. Lafayette Baker, initially set the Government’s mood for the conspiracy hunt. On taking charge of the pursuit of Lincoln’s assassins, he released an astonishing official order urging his detectives “to extort confessions and procure testimony to establish the conspiracy…by promises, rewards, threats, deceit, force, or any other effectual means.” No wonder he was Stanton’s most trusted lieutenant. And it is no wonder that there were numerous irregularities later discovered in the prosecution’s conduct and securing of witnesses.

On May 13, the Military Commission heard testimony from a Canadian physician, James B. Merritt, that Booth, Surratt, and Atzerodt were parties in a previous scheme to kill Lincoln. The United States Government paid Dr. Merritt $6,000 for his testimony. After the defense discovered that prosecution witness Von Steinacker had a significant criminal record and was recently released from prison, the court initially denied the defense's right to cross-examine him despite his testimony linking Confederate officers to Booth. After General Holt finally agreed to Steinacker’s cross examination, the witness could be found.

On May 25, the Military Commission suddenly introduced the subject of (alleged) Southern mistreatment of Union prisoners of war as an issue in the conspiracy trial. This outrageous tactic was successful in raising the level of anger and resentment against the South, Jefferson Davis, and the defendants.

Probably the most damaging circumstantial evidence against Mary Surratt was the untimely arrival of a well disguised Lewis Powell at Mrs. Surratt’s door on April 17. This and her denial that she knew him created suspicions that were difficult to overcome. Numerous witnesses testified to her poor eyesight, and many more testified of her sterling character and religious devotion. No fewer than five Catholic priests testified to her impeccable character.

The Lincoln assassination conspiracy trial was a shameful violation of due process. Only the Salem Witch Trials in 1662 and the autumn 1865 trial of Henry Wirz, commandant of the Andersonville prisoner of war camp, are comparable in their injustice, malice, and despotism. I do not believe that “Stalinist” is too strong a word for the conduct of Stanton and his inner counsel.

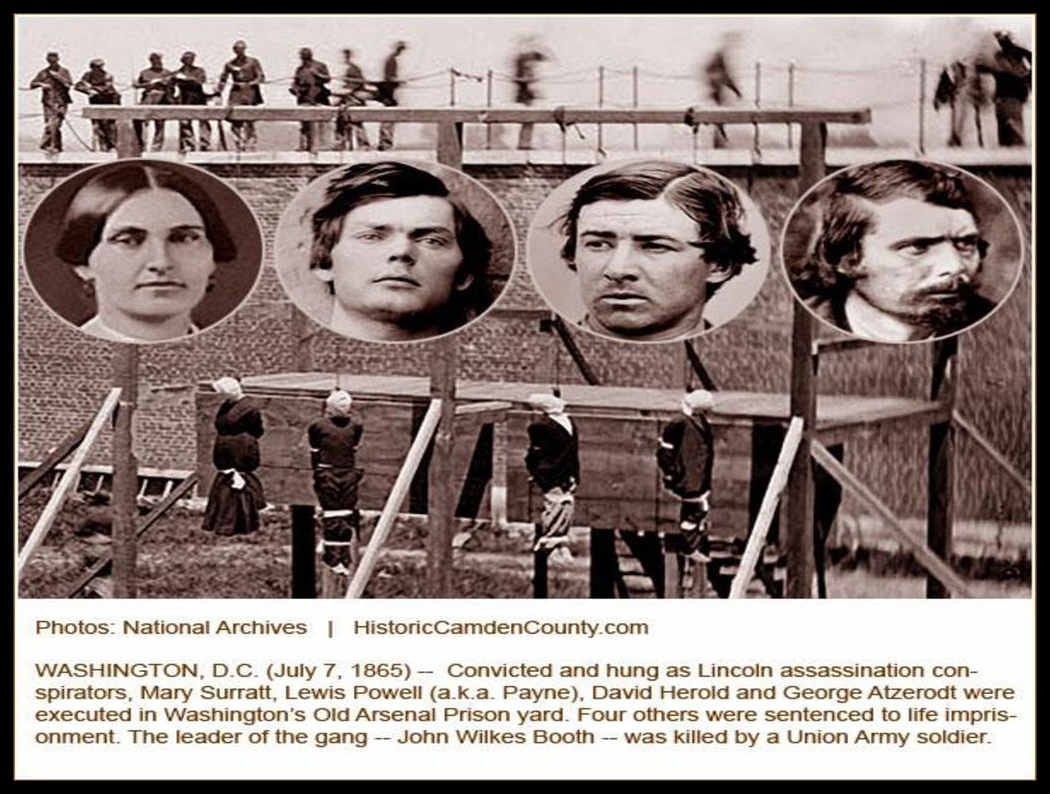

The Military Commission sentenced Atzerodt, Powell, and Herold to hang, the others were sentenced to long prison terms. Surprisingly, five of the nine officers on the Military Commission initially want either to acquit Mary Surratt or at least see she did not get the death penalty. But Edwin Stanton and Joseph Holt, supported by others in the Radical Republican ring, would not stand for it.

On July 7, 1865, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Lewis Powell, and Mary Surratt were hanged for conspiring in the assignation of Abraham Lincoln. Samuel Arnold, Samuel Mudd, and Michael O’Laughlin were given life sentences of hard labor at Dry Tortugas Prison, off Florida’s coast. Edward Spangler was given a lesser sentence. Years after the trial, Brigadier General William E. Doster, the attorney for Geroge Atzerodt and Lewis Powell, said that,

“The trial had been a contest on which a few layers were on one side and the whole United States on the other—a case in which the verdict was known beforehand.”

The rules of the Military Commission required six out of nine votes for conviction and sentencing. When they convened to consider their verdict and sentencing for Mrs. Surratt, they first proposed by a vote of five to four either to acquit her or at least spare her life. Judge Holt and Secretary Stanton were expecting the death penalty. Outraged and alarmed, Holt immediately hastened to Stanton’s office for consultation. Thirty minutes later Holt returned to the Commission with a compromise solution and intimidated the five dissenting officers—none of whom had any legal training into accepting it. “For the sake of legal consistency,” if the Commission would vote unanimously for the death penalty for Mrs. Surratt, they could draw up a petition asking the President for mercy in her case. Secretary Stanton would see to it that President Johnson received it favorably. With this compromise, the Commission could “save face” and yet spare the life of Mary Surratt. None of the defense counsels were consulted or made privy to this “compromise.” Major General Hunter, the President of the Military Commission, later said that “…this was done in violation of all principles of law and equity.”

But Stanton had no intention of keeping his part of their mutual understanding. Having convinced the Commission against their better judgement, to cast a unanimous vote to hang Mrs. Surratt, he would convince the President that it was absolutely necessary for her to hang. If an outraged public blamed Johnson for executing Mrs. Surratt, so much the better for Stanton’s Presidential ambitions. This would be just one of the double-crosses that the highly manipulative Stanton got away with in his legal and political positions.

The existence of the clemency plea for Mrs. Surratt was not known except to several Cabinet members and a close circle in the War Department until the civil court trial of John Surratt, Jr. in 1867. Upon demand, General Holt delivered it to the court but quickly retrieved it before it could be examined. Its existence was not publicly known until 1872. Below is the entire text, which was undersigned by Generals Hunter, Kautz, Foster, Ekin, and Col. Tompkins:

“The undersigned members of the Military Commission detailed to try Mary E. Surratt and others for the conspiracy and murder of Abraham Lincoln, late President of the United States, do respectively pray the President in consideration of the sex and age of the said Mary E. Surratt, if he can upon all the facts in the case, finds it consistent with his sense of duty to the country to commute the sentence of death to imprisonment in the penitentiary for life.”

This petition was certainly not designed to be a convincing argument for commuting Mrs. Surratt’s death sentence. Since Mrs. Surratt was forty-two-year-old, it would seem that making age a consideration in the petition weakened it considerably. Since none of the reasons are given that caused the undersigned officers to think that Mrs. Surratt’s guilt was either questionable or insufficient to warrant the death penalty, the credibility and gravity of the petition was substantially debilitated. Considering that this “compromise” was concocted by Holt and Stanton and the heavy-handed manner in which it was designed to be of little consequence, thereby contributing to the government murder of Marry Surratt.

In 1872, when the existence of the clemency petition became public knowledge, President Johnson claimed he had never seen it. Neither Johnson nor anyone on his staff officially acknowledged its receipt or made a formal response advising the Commission of its disposition. General Holt, however, firmly insisted that it was properly delivered with the other verdicts and sentences, and that Johnson did see it. There is evidence that President Johnson received many written request and personal pleas to commute Mrs. Surratt’s sentence, and that it was discussed in at least one Cabinet meeting, perhaps of limited attendance.

James Harlan, Secretary of the Interior in 1865, in a letter dated May 23, 1875, remembered a Cabinet meeting just after the conspiracy trial at which clemency for Mrs. Surratt was discussed. He recorded the words of Stanton to Andrew Johnson:

“Surely not, Mr. President, for if the death penalty should be commuted in so grave a case as the assassination of the head of a great nation, on account of the sex of the criminal, it would amount to an invitation to assassins hereafter to employ women as their instruments, under the belief that if arrested and condemned, they would be punished less severely that men. An act of executive clemency on such a plea would be disapproved by the Government of every civilized nation on earth.”

Thus, the agreement for Mary Surratt’s clemency that the petitioning officers thought they had with Stanton through Judge Advocate General Holt was betrayed. In the two days that transpired between President Johnson’s signing Mary Surratt’s execution warrant and her actual execution on July 7, numerous people petitioned the President for mercy. It is still not clear that if John Brophy and Anna Surratt tried to see him, since armed guards and Republican Senators James Lane of Kansas and Preston King of New York protected him. Only the President’s private secretary, Brigadier General R. D. Mussey, delivered messages and petitions to him or spoke to him directly. President Johnson was evidently not in a receptive mood for mercy. Reverand George Butler, who acted as chaplain for George Atzerodt and who made a social call on Johnson a few hours after the executions, gave this report on the President’s disposition:

“Concerning Mrs. Surratt…very strong appeals had been made for the exercise of executive clemency…but he could not be moved, for in his own significant language, Mrs. Surratt ‘kept the nest that hatched the eggs.’ The President further stated that no pleas had been urged in her behalf, save the fact that she was a woman, and his interposition upon that ground would license female crime.”

This clearly indicates that either the President was lying or that he did not receive the petitions that presented evidence of confessed perjuries and witness intimidation by the government or the state of Lewis Powell and John T. Ford. In a much later interview, he blamed his failure to commute Mary Surratt’s execution on General Mussey, who had blocked communications to him. General Mussey was only assigned as Johnson’s private secretary for a few months and may have been an appointment suggested by Stanton.

Col. William P. Wood, superintendent of the Old Capitol Prison while Mrs. Surratt was there, had been convinced of her innocence. Just before the execution, he rushed to the White house hoping to see President Johnson and make an appeal for mercy on her behalf. He was met there and blocked from entering by Col. Lafayette Baker, Stanton’s chief detective, who held a signed order from Stanton specifically prohibiting Wood’s admission to the premises. In an updated article which appeared in the Washington Gazette shortly after the death of Stanton in 1869, Wood revealed an interesting conversation with President Johnson:

“Some time after the execution of Mrs. Surratt, President Johnson sent for me and requested me to give my version of Mrs. Surratt’s connection with the assassination of President Lincoln. I did so, and I believe he was thoroughly convinced of the innocence of Mrs. Surratt. He assured me he sincerely regretted that he had not given Mrs. Surratt the benefit of Executive Clemency and strongly expressed his detestation of what he termed ‘the infamous conduct of Stanton’ in keeping these facts from him. I assured him of my unchangeable friendship for Mr. Stanton…while I regretted the course of adopted by the Secretary of War towards Mrs. Surratt…”

In 1867, John Surratt, Jr. was brough back to the United States for trial as a Lincoln assassination conspirator. Stanton failed in his attempt to subject him to trial by a military commission. The rules of evidence, the introduction of previously suppressed evidence (such as Booth’s diary), and the due process required by a civil court made it impossible to convict Surratt and was released. In 1866, the Supreme Court of the United States had decisively confirmed the Constitutional principle that military courts have no jurisdiction or authority over civilian cases, if the civil courts are open. Had Mary Surratt been tried in a civil court, she would never have been convicted. Nor it is likely that George Atzerodt or David Herold would have received the death penalty, nor would Dr. Mudd have been convicted of anything. The civil trial of John Surratt exposed many injustices that a free people must never again tolerate.

Before leaving office in 1869, President Johnson pardoned Dr. Mudd, Sam Arnold, and Edward Spangler. Michael O’Laughlin died of yellow fever in 1867 while imprisoned at Dry Tortugas.

There is a bronze plaque near the grave of Mary Surratt at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Washington D.C. It seems an appropriate epitaph for a woman who suffered enormous injustice, and whose public memory is still scarred by malicious and false witness:

“The souls of the just are in the hands of God, and the torment of malice shall not touch them. In the sight of the unwise they seem to die, but they are at peace.”

Understanding the story of Mary Surratt, her trial, and hanging is essential to understanding the police state justice administered by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton after the assassination of the President. Witnesses were bribed, tortured, coerced, and threatened with death to obtain a conviction. It also shows Stanton’s ambitious and devious nature. Combining the trials of Mary Surratt and Henry Wirz, the patterns of outrageous injustice become clear.

References and Reading:

Abraham Lincoln’s Execution; John Chandler Griffin, 2006

Mary Surratt: An American Tragedy; Elizabeth Steger Trindal, 1996

Why Was Lincoln Murdered? by Otto Eisenschiml, 1937

The Judicial Murder of Mary Surratt; David Miller DeWitt, 1895, 2014

Mrs. Surrat should have known that others often judge us by the company we keep. (Guilt by association)

Thank you for that great post. I've been president of a court martial board while a squadron commander in Turkey. Training was very minimal for our duties. Fortunately, the defendant had confessed to his crime (drugs) and it was essentially a no-brainer. It saddened me for the young man to have ruined his career, but it was a clear cut case violating the UCMJ.