The Impeachment of President Andrew Johnson the 17th President of the United States

"Let them impeach and be damned." ~Andrew Johnson

“Our government springs from and was made for the people—not the people for the government. To them it owes allegiance; from them it must derive its courage, strength, and wisdom.” ~Andrew Johnson

President Lincoln chose Andrew Johnson, the Union Military Governor of Tennessee, to be his Vice-Presidential running mate on the “National Unity” or Union Republican ticket in 1864 in hopes of garnering the votes of pro-war Democrats in the November election. Johnson had been a Democratic Senator from Tennessee, but he refused to side with his state when Tennessee seceded in 1861. Politically, Johnson was a Jacksonian conservative. He believed strongly in state rights and limited constitutional government, but just as strongly, he rejected the concepts of succession and nullification. In Tennessee politics he had identified himself with the interests of the common people and against the interests of the wealthy planter classes. Like most Democrats and Conservative Republicans, he supported the constitutionality of slavery. Although his political beliefs are very close to other Southern Democrats except for secession, he was known for his severe and threatening criticisms of secessionists.

Because of Johnson’s harsh remarks and sometimes vengeful remarks about secessionists, the Radical Republicans assumed he would support their radical aims for reconstructing the South after the war. The Radical Republicans were very uneasy about Lincoln’s March 4, 1865, inauguration speech in which he indicated a lenient plan for reconstructing the South.

Lincoln believed that a magnanimous policy on reconstruction would avoid further regional conflict and pave the way for rebuilding political alliances between Northern Republicans and Southern business interests. The Radicals, however, probably judged rightly that Southern politicians would not support the Whig-Republican policies of highly protective tariffs and government subsidies for industry or a national bank (essentially fiat money). They believed that welcoming Southern states back into the Union without radically reconstructing Southern society would only result in more Democrats in Congress, thus threatening continued Radical Republican dominance and control. The Radicals believed the South deserved to be severely punished and exploited and made into Republican states before reentering the Union. The latter objective was to be achieved by enfranchising black voters and disenfranchising Confederate veterans, thus giving the radicals permanent political dominance in the South and thereby the nation.

When the Radicals realized that Johnson intended to follow the same lenient Reconstruction policies as Lincoln, they began to oppose him strongly and tried to limit his power and influence. The first confrontation between the Radicals and Johnson began when the Radical dominated Congress refused to seat the new Southern delegates elected in 1865. This left them free to impose their punitive policies on the South. Their excuse was that Southern states were trying to circumvent the abolition of slavery, instituting “black codes” to limit the civil rights of blacks and failing to control racial violence. There's little truth to these excuses but campaigning against the faults of the South was a successful political strategy in the North. Johnson pointed out the hypocrisy of Northern legislators, whose states (for example: Indiana, Illinois, Ohio and Oregon) had far more restrictive “black laws” than any in the South, using this issue as an excuse to impose punitive measures on the South.

In February 1866, Johnson successfully vetoed the first Freedman’s Bureau Bill. This bill would have extended many civil rights to the newly freed blacks, but it also authorized the confiscation of land from whites for redistribution to the blacks, established previously unheard social welfare programs for blacks but not for whites, and established an extra constitutional military tribune system for whites accused of violating the rights of blacks. Johnson noted this in his veto message that:

“A system for the support of indigent persons in the United States was never contemplated by the authors of the Constitution; nor can any good reason be advanced why, as a permanent establishment, it should be founded on one class or color of our people more than another… The idea on which the slaves were assisted in freedom was that on becoming free they would be a self-sustaining population. Any legislation that shall imply that they are not expected to attain a self-sustaining condition must have a tendency injurious alike to their character and their prospects.”

Congress would pass a modified and only slightly less heinous version of Freedman’s Bill in February 1867 and was then able to override Johnson's veto.

The next month Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This bill duplicated many civil rights laws already passed by the states, but its real intent as seen by Johnson was to grant the federal government unlimited power to intervene in state affairs. It also granted revolutionary police powers to Freedman’s Bureau officials to enforce all civil rights laws. Johnson feared it was so severe that it might resuscitate an armed rebellion. Congress overrode Johnson’s veto. Several provisions of this Act were later incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment, which Johnson strongly opposed, rightly predicting that it would lead to a consolidation of power at the federal level, in effect turning the Constitution upside down.

In May of 1866, there was a race riot in Memphis. The conflict was between black Union soldiers and white Irish police of recent Northern origin, but the Radicals made good use of it as an example of Southern intolerance and violence.

By early summer of 1866, the new state government in Louisiana had elected state legislators, state executive officers, and a Mayor for New Orleans. Much to the displeasure of the Radical Republicans, Louisiana was returning to Democrat Party control, and it was only a matter of time before a Democratic Governor might also be elected. The Republicans immediately laid plans for overturning the newly elected government. They called for a reconvening of the 1864 Union Military Government appointed convention to amend the state constitution and to hold new elections. Only those eligible to vote in 1864 (mainly the Radical Republicans) would be allowed to vote for delegates. The plan was to void the Democratic electoral victory, disenfranchise most Confederate veterans, and in enfranchise blacks, thus establishing a sizeable republican political dominance.

Hearing of this revolutionary attempt to overthrow the legally elected government of Louisiana, President Johnson demanded that the Radical Republican Governor, Madison Wells, halt this proceeding. Wells ignored the President and continued to pursue plans to displace the recently elected conservatives and establish a lasting Republican dominance. Outraged at this, Mayor Monroe of New Orleans and Lieutenant-Governor Voorhies called for Union General Baird, commanding federal forces in the city, to prevent the illegal Radical convention from taking place. Braid declined to interfere and only offered to protect the convention from the city from mob action.

On the Friday before the Monday, July 30, 1866, convention, the Radicals organized a mass meeting denouncing Johnson and then urged blacks to arm themselves to protect their rights and any attempts by New Orleans authorities to break up the convention. A white radical threatened that “the streets will run with blood,” if there is any interference with the convention, and urged the mainly black gathering of several thousand to come in force on Monday.

Alarmed at this, General Baird telegraphed President Johnson for instructions, unknowingly that all telegraphs to the President, came through the War Department and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

On that Monday, incited by the radicals, a variously armed and intoxicated mob of freedmen swarmed the convention and came in conflict with Democratic protesters and New Orleans police. About fifty people were killed in the ensuing riots and mayhem, most of them were blacks. General Baird's Federal troops arrived after the fact.

President Johnson's telegram from General Baird was not received until the riot was over. Secretary Stanton, with no explanation, had deliberately withheld it from him. As news of the bloody riot was received in the North, the Radical Republicans and their allies in the press and pulpit exploded with inflammatory denunciations of the South and Johnsons lenient Reconstruction policies. By this time, President Johnson was thoroughly disenchanted with Stanton.

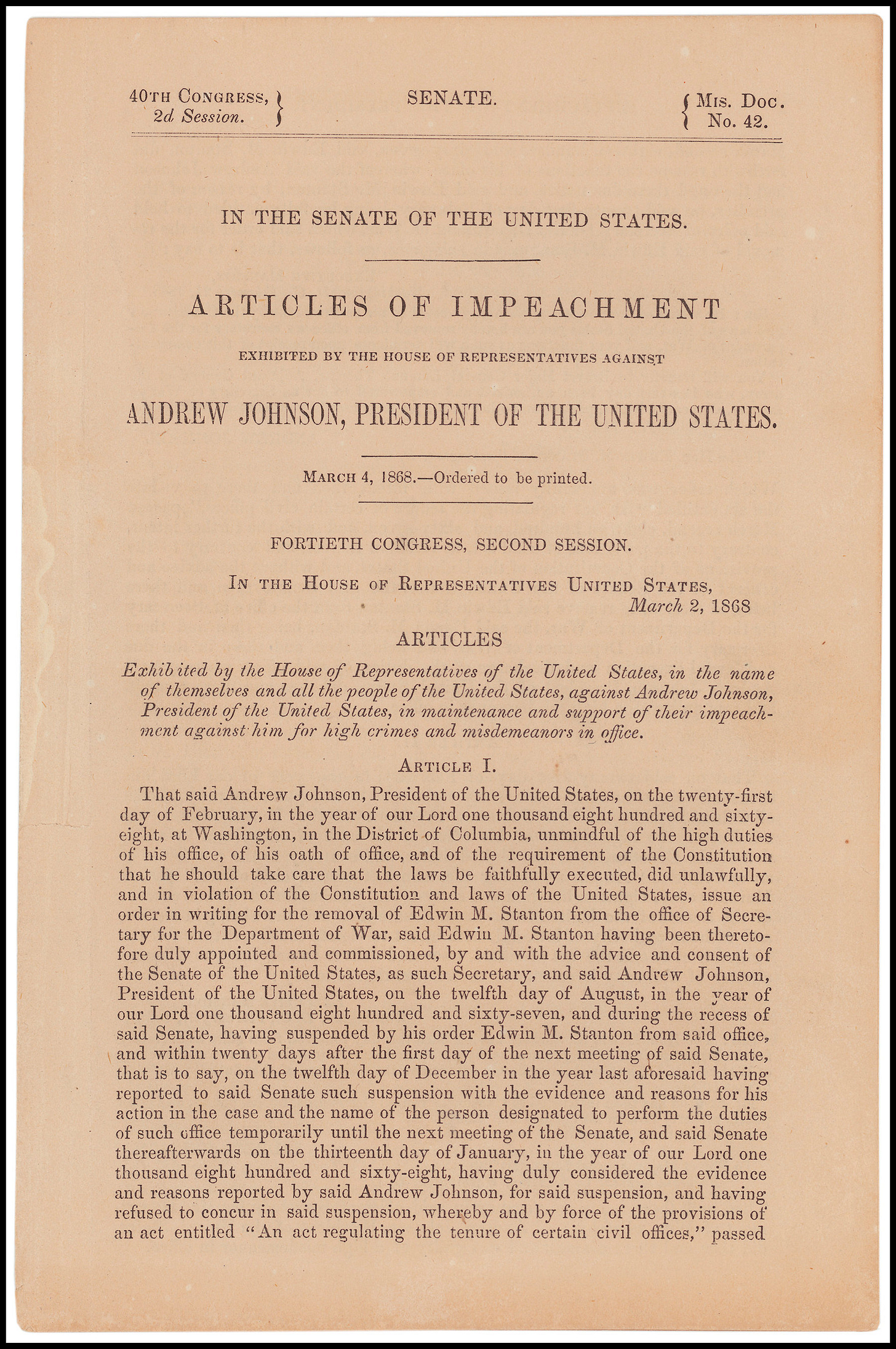

In February 1867, at the behest of Stanton, the Radical dominated Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act, Prohibiting the president from dismissing any officer confirmed by the Senate without Senate approval. This act was primarily intended to keep Secretary Stanton, a sympathetic ally to the Radical Republicans and a strong proponent of stern Reconstruction for the South, at his very influential post. Congress promptly overrode the President's veto of the bill.

In March of 1867, when most Southern states had rejected the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress passed the infamous Reconstruction Act, putting most Southern states under military governments, enfranchising blacks, disenfranchising most Confederate veterans, establishing corrupt carpetbagger governments, imposing debilitating taxes, and a tyranny over the South that would last until 1877. Passing the Fourteenth Amendment was a prerequisite for Southern states to enter the Union. President Johnson's strong protest and veto were overwritten.

In early August of 1867, President Johnson learned from the trial of John Surratt and a conversation with Colonel William P. Wood, Superintendent of the Old Capitol Prison in 1865, that Edward Stanton had deliberately suppressed a petition of mercy from five officers on the Lincoln Assassination Tribunal that would have caused him to spare the life of Mary Surratt in July of 1865. Johnson knew that the Radical Republicans would try to impeach him for violating the Tenure of Office Act if he attempted to fire Stanton. But on the very day he learned of Stanton’s treachery regarding the trial and sentencing of Mary Surratt, he decided that justice and honor required him to dismiss Stanton.

The relationship between President Andrew Johnson and the Radical Republicans who dominated Congress was very strained in the two years following his assumption of office. He was strongly opposed the harsh terms of Reconstruction imposed upon the South and rigorously resisted Congressional usurpation of power over the states. His relationship with his Secretary of War, Edward Stanton, was particularly strained. Stanton had a clandestine alliance with the radicals even while serving under Lincoln and had become, not only a key ally of the radicals in Congress, but also one of their most influential leaders. He was among the most determined proponents of a punitive and repressive Reconstruction as a means of preventing conservative Democrats from gaining power in the South and the nation. Also having his own presidential ambitions, Stanton frequently used furtive and underhanded tactics to undermine Johnson.

During the 1867 trial of John Surratt, who is accused of conspiracy in the Lincoln assassination (as was his mother, Mary Surratt), it was revealed that Stanton had withheld John Wilkes Booth's diary from evidence during the previous 1865 conspiracy trial. There was also controversy over missing pages of that diary, disputing whether more pages were missing when examined during John's Surratt's trial than when recovered from Booth's body in April 1865. There were many embarrassing revelations that the War Department had used torture, threats, and bribery resulting in perjured testimonies in prosecuting its case against Mary Surratt. Most alarming to the public and to President Andrew Johnson was the revelation that five officers on the military tribunal had submitted a plea for mercy for Mary Surratt, but that petition had been suppressed, resulting in her hanging on July 7,1865.

Johnson called his Chief of Secret Service, Colonel William P. Wood (ironically appointed on July 5, 1865, the day Mary Surratt and three others were sentenced to death) to inquire as to his opinion on the matter. Wood was a close confidant of Stanton, but while the commandant of the Old Capitol Prison during Mary Surratt’s stay there, he had to believe she was innocent of any complicity in the assassination of Lincoln. Wood’s background would seem incongruous with sympathy for Mary Surratt. She was a devout Roman Catholic, and he had rejected that church and turned to atheism. He was a radical abolitionist and had even helped to train some of John Brown's men before their infamous raid on Harpers Ferry, but he refused to approve Brown's moving arms across the state border. Regardless of their contrasting worldviews, Wood had attempted to deliver a statement strong conviction of Mary Surratt’s innocence to President Johnson before her hanging, but he had been stopped by Stanton’s Chief Detective, Colonel Lafayette Baker, carrying a restraining order specifically directed to Wood and signed by Stanton.

Colonel Wood’s conversation convinced President Johnson that Mary Surratt was innocent of any significant wrong-doing and should not have been hanged. Though a close friend of Stanton, Wood admitted that Stanton’s conduct regarding the investigation, trial, sentencing, and finally the hanging of Mary Surratt had been regrettable. On August 7, 1867, President Johnson addressed and signed a letter to Stanton, which read:

“Sir: Public considerations of high character constrain me to say that your resignation as Secretary of War will be accepted.”

Stanton, however, refused to vacate his office, although on August 12, Johnson temporarily suspended him and designated General Grant as Acting Secretary of War. Congress was not in session at the time.

When Congress returned on January 13, 1868, the Senate refused to concur with Stanton's suspension by a vote of 35 to 16. President Johnson then formally dismissed Stanton, designating General Lorenzo Thomas as his replacement.

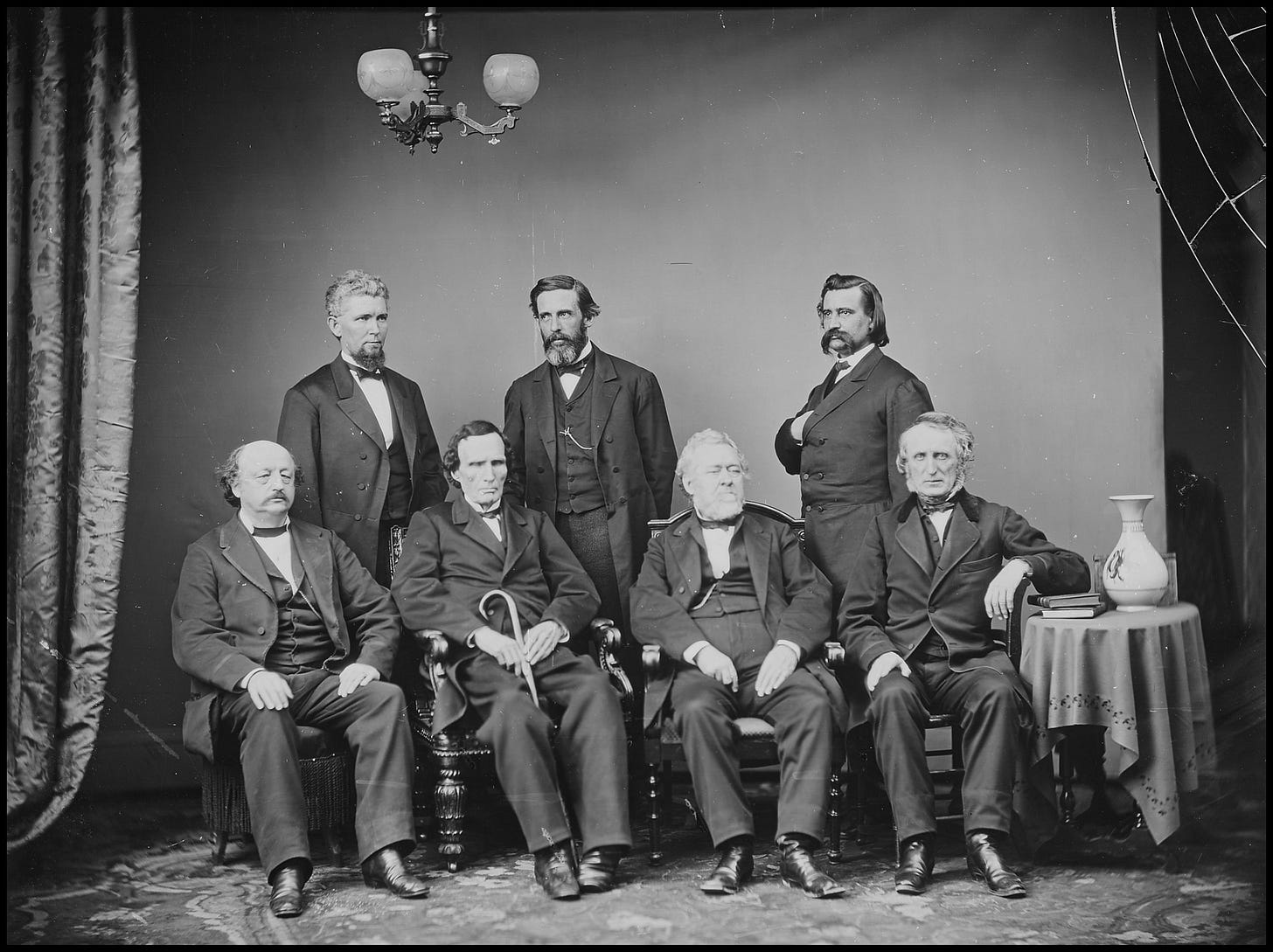

Led by Radical Republicans Thaddeus Stevens, Benjamin Butler, and John Bingham, The U.S. House approved an impeachment resolution by a vote of 126 to 47. Stevens of Pennsylvania was the House leader of the Radical Republicans and so powerful that some referred to him as “the Boss of America.” Butler of Massachusetts was a former Union Army General whose conduct as commander in the Union forces occupying New Orleans during the war earned him the sobriquets “Beast Butler” and “Spoons Butler” for his outrageous order to treat Southern women who showed any disrespect to Union officers as prostitutes and for his infamous looting of Southern households. He also had a young man hanged for cutting down an American flag. Following the assassination of Lincoln, Butler, speaking on the floor of the U.S. House, accused President Johnson of complicity in the assassination. Bingham of Ohio had been one of the assistant prosecutors at the trial of Mary Surratt and others alleged Lincoln assassination conspirators in 1865. It was he who inscribed, according to the directions of Stanton and Army Judge Advocate Holt, the military tribunal’s petition requesting mercy for Mary Surratt, which was then, by various means suppressed. Stanton had also made Bingham promise never to reveal what they knew concerning the Lincoln assassination and the trial of Mary Surratt.

Eleven articles of impeachment were presented to the Senate for trial. The main issue was Johnson's violation of the Tenure of Office Act that Congress had passed in 1867 to protect Stanton. This act was later ruled unconstitutional. The real issue was that the Radical Republican majority disagreed with Johnson's lenient plan to restore the Southern states to the Union. Their plans were to punish and loot the South severely and structure its electorate to assure long-term Republican dominance in the South and thus the nation. Johnson had also criticized the Radical Republicans and exposed their intent in public speeches. In truth, the Tenure of Office Act had been passed as a means of trapping Johnson into impeachment. With Johnson out of office, Radical Ohio Republican Senator Benjamin Wade, Speaker Pro-Tem of the Senate, would become President, and the way would be cleared for unopposed social and economic revolution in the South—the key to long term Republican power and national dominance. This would assure the perpetuation of high protective tariffs and government subsidies for Northern industry and the fiat money of a national bank.

On March 30, the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson commenced in the Senate. A two-thirds majority was necessary for conviction. Acting on presiding officer and judge was Chief Justice Solomon Chase, a Radical Republican, who had been Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary. The Senate floor leaders for conviction were Benjamin Wade and Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner, the acknowledged leader of the Radical Republicans in the Senate. Johnson was defended by Henry Stanbery, who temporarily resigned his position as Attorney General to defend his President.

The opening argument for impeachment was made by house impeachment manager, Benjamin Butler. The closing argument for impeachment was made by Thaddeus Stevens, and the closing argument for defense by Attorney General Stanbery. Thirty-six votes were required for the two-thirds necessary for conviction. On May 16, the House managers brought up Article XI in regarding the President's speeches against the effort of Radical Republicans to impose outrageously harsh Reconstruction terms on the South. The vote was 35 for conviction and 19 against, one vote short of conviction. On May 26, the Senate failed to convict Johnson on articles II and III by the same vote and abandoned further attempts at a conviction. President Johnson was acquitted, and the Radical Republicans’ dubious attempt to remove him from office (due to what were essentially policy disagreements) was frustrated. Six Republicans heroically defied the powerful and ruthless leadership of their party by voting to acquit Johnson. The Senate, however, retaliated against Henry Stanbery by shamelessly refusing to reconfirm him as Attorney General.

Perhaps the best summary of the Presidency of Andrew Johnson and his conflict with Stanton and the Radical Republicans came from Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy under Lincoln and Johnson:

“The real and true cause of assault and persecution was the fearless and unswerving fidelity to the president to the Constitution, his opposition to central Congressional usurpation, and his maintenance of the rights of the states and of the Executive Department against legislative aggression… carried on by a fragment of Congress that arrogated to itself authority to exclude States and people from their constitutional right of representation, against an Executive striving under infinite embarrassments to preserve State, Federal and Popular Rights.”

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s star began to fall with Johnson’s acquittal. The revelations of his conduct during the Lincoln conspiracy trials and especially that relating to the hanging of Mary Surratt no doubt figured in his failure to achieve his ambition to become President. Ulysses S. Grant was the successful nominee of the Republican Party in 1868. Grant did nominate Stanton to a Cabinet post, but after much persuasion by Congressional Republicans, the wary Grant finally nominated Stanton to the Supreme Court. He was quickly approved by the Senate, but Grant delayed making the appointment.

In December of 1869, Stanton requested his old confidant, Colonel Wood, to visit him and explain why Grant was delaying his appointment to the Court. Wood informed him of his opinion, which he never disclosed publicly. Stanton then lamented that “the Surratt woman haunts me so that my nights are sleepless, and my days are miserable.” He added that he wished that Wood had tried harder to stop her execution, though he had admitted he was personally responsible for blocking Wood's efforts. The next day, December 24, 1869, Edwin Stanton died at his home.

While Republicans held more than a two-thirds majority in the Senate, several Republicans had already indicated they would vote “not guilty.” Combining those votes with the known Democratic votes, there was little room for error for those who desired a guilty verdict.

The deciding vote turned out to be that of Edmund Ross. Those who knew him thought that Ross would vote in favor of conviction. However, when his turn to vote came, Ross very quickly voted “not guilty,” thus guaranteeing there would not be enough votes to convict President Johnson.

To this day, Edmund Ross’s motives for voting “not guilty” are still being debated. One theory is that President Johnson’s friends made use of a $150,000 slush fund to bribe the Senator. Another is that he was not happy with the prospect of Benjamin Wade, president pro tempore of the Senate, becoming President. It has even been put forward that multiple Senators voting after Ross would have cast the deciding “not guilty” vote if Ross had not, so Ross’s act was not as “heroic” as some have put forward.

Regardless, Ross’s vote sealed the “not guilty” verdict. Unsure of the next step forward, Republicans recessed temporarily before coming back 10 days later to vote on Articles 2 and 3. Both of those votes failed by the same one-vote margin, effectively ending President Johnson’s impeachment trial. Johnson went on to serve the last few months of his term.

Congress eventually repealed the Tenure of Office Act in 1887.

There are several good books about Andrew Johnson, the 17th President of the United States, 1865-1869. Andrew Johnson, by Annette Gordon-Reed, 2011. The Impeachers, Brenda Wineapple, 2019. The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson, by Michael Les Benedict, 1999

Another great one. I just read The Impeachers a few months ago. It wasn't the most "readable" but it had a lot of great information.

I have to say I am quite biased in regards to Andrew Johnson. Johnson, as you probably are aware of was sold into a contract of apprenticeship. learning the trade of tailoring and escaped and became somewhat well-to-do as a tailor. No matter the issue of union, I greatly admire Johnson's stand which took a great deal of personal courage in his home state.

I think he continued to show the same courage as president. I'm not taking a stand here on the issues but Johnson's courage, in my mind, should put him at the top of any list of Profiles in Courage. Few political leaders in America have ever exhibited such personal strength in facing what he though was right, no matter the personal danger or the political consequences.

For me he stands tall for that and deserves to be more highly regarded, not thrown to the dung-heap as the worst,or one of the worst presidents.

I don't know about his politics and whether he was right or not right in his perspectives, that can be a mixed bag because it was such a temporary aberration of the American political consequence. There was at the time a desire to punish the south, even by those who would ina few years have no more desire to do so. Punishing the south therefore accomplished little and nothing whatsoever was done about the WageMasters in the north and reconstructing the entirety of the economic systems of oppression. Since the future was only delayed by a decade it was all futile.

In that sense Johnson was possibly historically correct but the south generally didn't respect his stand with the Union and the north wrote the history of his {sic} bigotry.

P.S. I have completed my own reflections on freedom and in part IV I praise your work.

My little articles are from a psychological perspective; and thus I referred to this column as a prime example of the psychological torture that the south endured as a result of the war---even many who did not participate in slavery and despised the Slaveowners--as Johnson did--who nevertheless never were able to feel they had been given a choice in their own future.