The Secession Was Founded on Legal Rights

This is an opinion piece. “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to that State, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

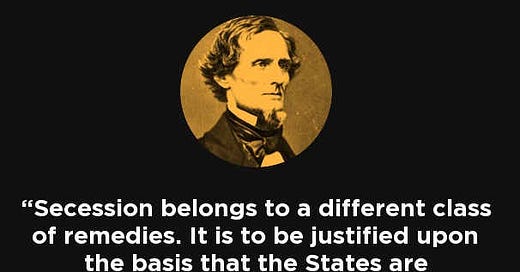

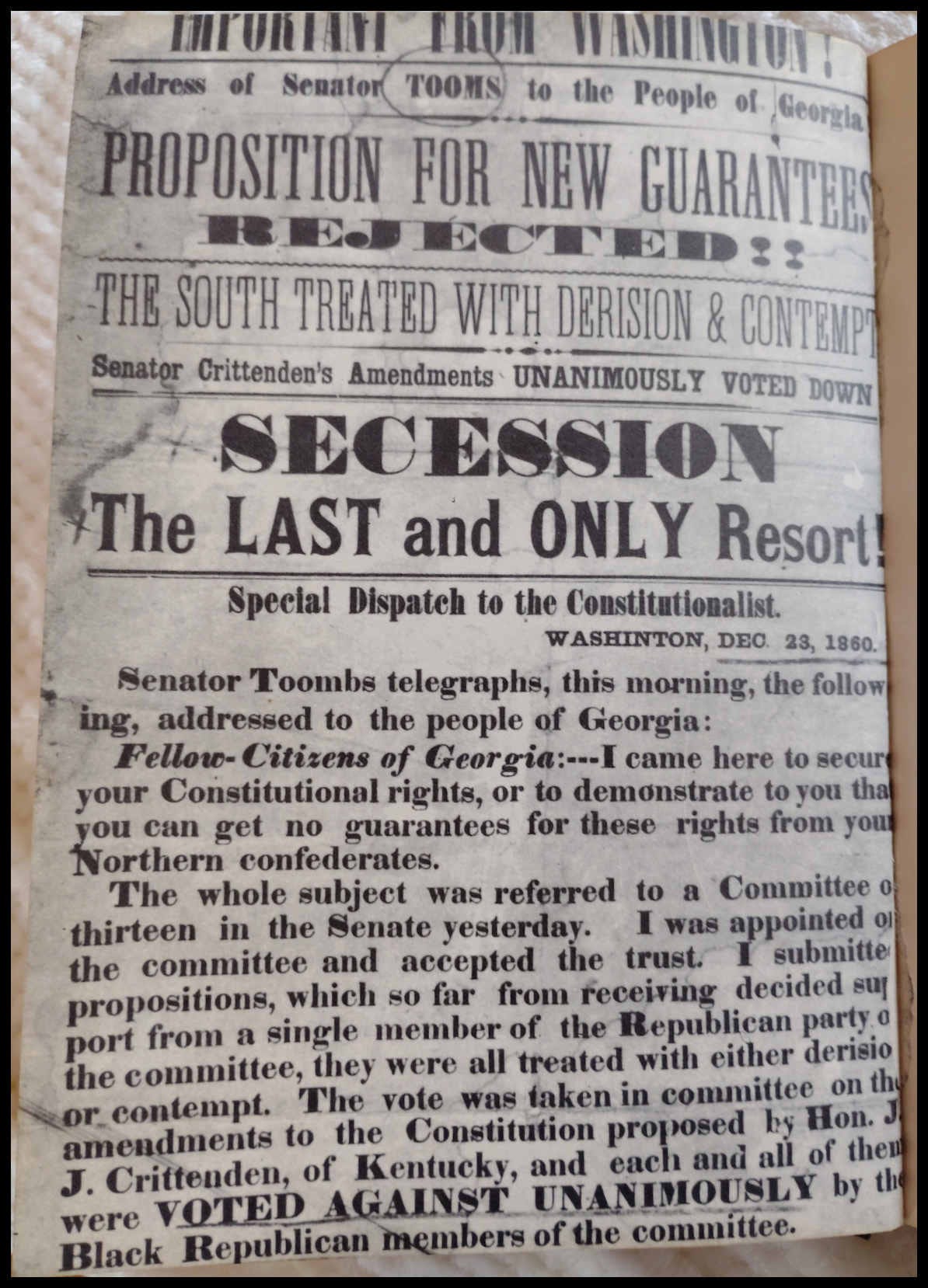

Secession rested upon fundamental law. The secession from the United States by the several states of the South in 1861, which led to the war between the Confederacy and the Federal Government aided by the remaining states, was within its constitutional rights found in that governmental instrument, the Constitution of the United States. Secession was the extreme means, in the sense that the right of a revolution is sometimes justified, for the purpose of preserving the sacredness and blessings of the written constitutional government.

Brush the cobwebs and preconceived notions from the mental vision and let us measure by the sternest logic and the strictest of universally recognized rules these sweeping grounds, standards of conduct for which our ancestors fought and for which many gave their lives, and for which our ancestors made the most supreme sacrifices. First, exactly what do we mean by secession? We need to examine specific conduct, not the mere academic definition of the word secession. The question before us is: What is meant by the secession of certain states in the southern part of the United States in 1861?

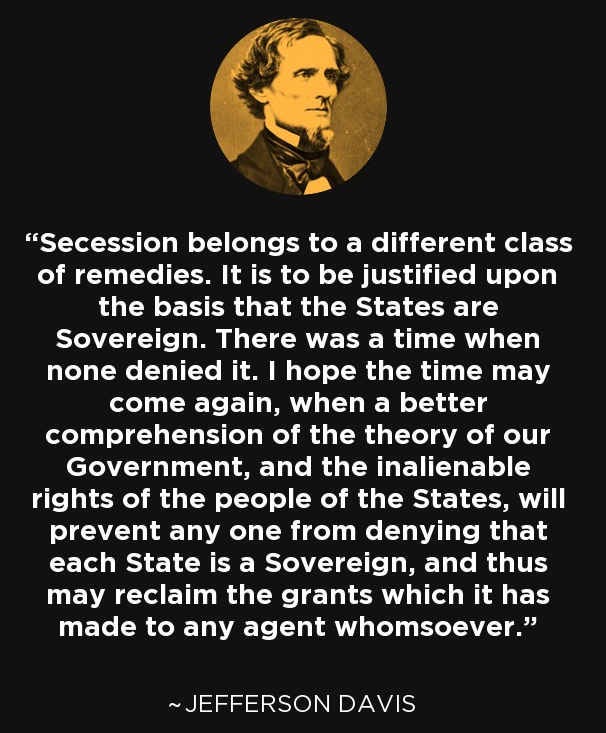

For the purpose of finding the legal ground upon which those Southern States acted, it is immaterial whether we regard the acts comprehended by the word secession in this connection as accomplished or attempted secession, but it is interesting to recall that those in the exercise of the chief functions of the Federal Government, and a large part of Northern people generally insisted in 1861 (contrary to prior Northern doctrine and practice) that no Southern State could secede, or could get out of the Union; while for years later, after the South had worn out her swords and had broken her bayonets, and her brave boys were mostly asleep beneath the golden rods of summer and the withering leaves of somber winter, the same pro-Union people generally and especially the bureaucrats of the United States Government were sordid and cruel in holding that the seceding States were out of the Union and as sovereign and independent States ceased to function as units of the Union. So, to avoid confusion of thought upon this point, it could be assumed without fear of successful contradiction that the seceding States were at least de facto out of the Union. That a course of conduct does not reach its final goal is no evidence that it was not legally taken. So, the secession here under consideration may be broadly and correctly defined as the act or acts of the Southern States, each exercising what we call its sovereign political powers, the purpose of which was to sever allegiance to and connection with the Union.

The Union was and yet is the relation between each State and a sovereignty known as the United States (or Federal Government) which was created by, and which exists by the Constitution of the United States.

Therefore, secession was the act of a State as such by which it at least sought to become and for a time was de facto independent of the United States, out of the Union, just as each colony became by revolution independent of and out of the British Empire back in 1776. Lincoln, the chief executive of the United States, took the position that no State could withdraw and become completely independent. So, as the Southern States one by one persisted in the secession course, Lincoln sent Federal troops into the South to re-establish what was broken and to maintain Federal authority—not to free the slaves or affect in the least slavery. To resist this invasion by armed force the seceding States raised troops to defend the newly asserted independence, just as the colonies did back in 1776 with the regard to Great Britian, the Southern States were organizing in the meantime a central government known as the Confederate States of America. Thus, the war came on at a rapid pace.

Since secession was either a withdrawal or an effort to withdraw from the Union, to become completely independent of the government of the United States, our first question should be: What is the relation of each state to the Union? In finding this relation we necessarily define the government of the United States, also called the Federal Government.

The first thing we discover, as just intimated, we come to see exactly what the American Union is, when we really discern the universally acknowledged fundamental of all fundamentals regarding its existence, is that the Constitution is the one source of its power and authority, the sole source of its strength; and so outside of or minus this Constitution there would be no Union, and no United States of America. This great, primary important truth is one of the settled and established facts concerning our American government.

In 1861, when Marshall, of Virginia, and Story, of Massachusetts, two great constitutional lawyers, members of the bench, the Supreme Court of the United States, the entire bench in agreement said:

“The government, then, of the United States can claim no powers which are not granted to it by the Constitution, and the powers actually granted must be such as are expressly given or given by necessary implication.” (1 Wheaton, U. S. Reports, 326.)

In 1906, Justice Brewer, speaking for the same high court said: “As heretofore stated, the constant declaration of this court from the beginning is that this government (of the United States) is one of the enumerated powers.”

Then, as showing the place where that enumeration is found, the court in 1906 quoted with the entire approval the words from the decision, as written by Story, of Massachusetts, in 1816, “the United States can claim no powers which are not granted to it by the Constitution.”

This fact, a fundamental truth, is found not alone in the decisions of the courts; but it is the great principle by which all departments of the Federal Government are admittedly controlled. It is the practical fact in all the activities of the general government.

There is another similarly fundamental truth, and practical fact: The United States Government does not enjoy spontaneous or original or inherent sovereignty; all its sovereign powers are delegated. This fact is just as universally and as practically recognized as the other. “The government of the United States is one of delegated, limited, and enumerated powers,” is one of the hundreds of statements of this truth repeated by the Supreme Court case of the United States vs. Harris (106 U. S. Supreme Court Reports, 635.)

There is a dispute whether the States created the Federal Government, delegated to its powers it has, or whether it is the creature of the whole people of the United States acting as a great sovereign political unit. It seems to me, since the Constitution went from its framers back to the States, back to each separate State for its independent action, too clear for argument that it is the creature of the States, particularly since three-fourths of the States had to approve it before it became operative, and three-fourths may now amend it. (Constitution, Art. V.)

And all the more that this must be true when we recall at the formation of the Federal Government and before the ratification of the Constitution, “thirteen dependent colonies became thirteen independent States”; that is, in other words, before the ratification of the Constitution “each State had a right to govern itself by its own authority and its own laws, without any control by any other power on earth.” (Ware vs. Hilton, 3 Dallas, 199; McIlvaine vs. Coxe, 4 Cranch, 212; Manchester vs. Mass., 139 U.S., 257; Johnson vs. McIntosh, 8 Wheaton, 395; Shivley vs. Bowlby, 152 U.S. 14). But we need not stop debating this question here or let it bother us in even considering secession. At the time of secession, we had a certain kind of government, the same as we have now, in fact; and however, it was created we know that the universally admitted facts are that the Federal Government gets its vital breath from the Constitution; that all its powers are enumerated in that Constitution, and we are delegated through it.

Regardless of from whom or from what delegated, this fact of the delegation from some other completely sovereign power is an important one in considering secession. Many errors have been made by confusing the powers of the United States as they might be under the general nature of sovereignty but what they really are is under the limited and delegated sovereignty it really has. “The government of the United States has no inherent common law privilege, and it has no power to interfere in the personal or social relations of citizens by virtue of authority deductible from the general nature of sovereignty,” as a recognized law authority correctly states the actual, practical, and accepted fact. (39 Cyc. 694).

Then, the United States being a government of limited powers, lacking any power over numerous subjects which must be controlled or produce chaotic confusion, it follows that the powers or sovereignty wherein the United States is limited, which were never entrusted to it, must rest somewhere. As summarized by a leading law authority, deduced from universally admitted decisions, here is full government in America:

“The powers of sovereignty in the United States are divided between the government of the Union and those of the States. They are each sovereign with respect to the objects committed to it, and neither sovereign with respect to the objects committed to the other.” (26 Ruling Case Law, 1417.)

Here is the same truth in the language of justices of the supreme court of Massachusetts:

“It was a bold, wise and successful attempt to place people under two distinct governments, each sovereign and independent within its own sphere of action, and dividing the jurisdiction between them, not by territorial limits, and not by the relation of superior and subordinate, but by classifying the subjects of government and designating those over which each has entire and independent jurisdiction.” (14 Gray, Mass. Reports, 616.)

In 1904 the Supreme Court of the United States stated the same fact in these words:

“In this republic there is a dual system of government, National and State, and each within its own domain is supreme.” (Matter of Heff, 197 U.S. 505.)

In an opinion written for the court by Justice Day, of Ohio, the same high court in 1917 said:

“The maintenance of the authority of the States over matters purely local is as essential to the preservation of our institutions as is the conservation of the supremacy of the Federal power in all matters entrusted to the Nation by the Federal Constitution. In interpreting the Constitution, it must never be forgotten that the Nation is made up of States to which are entrusted the powers of local government. And to them and to the people the powers not expressly delegated to the National Government are reserved. The power of the States to regulate their purely internal affairs by such laws as seem wise to the local authority is inherent and has never been surrendered to the general government.” (Hammer vs. Dagenhart, 247 U.S. 273.)

By these words, it is clear and certain, the Union is one of the States—States each of which is as absolutely and independently sovereign with reference to the specific, delegated and enumerated objects and affairs within its jurisdiction solely and by virtue of the Constitution. That distinction is; the sovereignty of the United States is delegated and that each State is inherent. Therefore, some light upon the sovereignty of the States may rightly be had from a consideration of the nature of sovereignty in general.

These all-important facts were well understood and recognized by the seceding States in 1861. The war of 1861 to 1865 did not change the nature of our government or abated in the least the dignity of the inherent sovereignty of each State. Over and again the Supreme Court of the United States finds it necessary to emphasize this truth. Many persons are under the erroneous impression that in any and all cases of unreconcilable conflict between the United States and a State over any and all subjects the decision and action of the United States becomes the supreme law of the land. No, this is not so, as the above evidence proves to any open mind. I sincerely hope that particularly our young men and women of the South will bear this governmental fact in mind when considering the secession of the Southern States in 1861. And this too: Each State has a most vital attribute the United States has not under law of the Constitution. Without the States or in case of an ignored or otherwise abrogated Constitution, the United States as a government, the Union, would cease to exist. On the other hand, in the words of the Supreme Court in 1868 when there certainly were no pro-secessionists on the bench:

“The people of each State compose a State, having its own government and endowed with all the functions essential to separate and independent existence.” (Lane County vs. Oregon, 7 Wallace, 71; Texas vs. White, Id. 725; Pollock vs. Farmers’, etc., 157 U.S. 560; N. B. Co. vs. U. S., 193 U. S. 348.)

This peculiar and dual government is distinctively the American government. These definitions and illustrations state it as it was as soon as the Constitution superseded the Articles of Confederation, as it was at secession, as it is. The results of the war for the independence of the Confederacy somewhat dulled the usual conception of the reality, of the dignity, and of the real nature of State sovereignty. My sincere hope is that we shall from now on swing back to the true grasp of what the American States each is, to that universal understanding which the States had when the Constitution was adopted for all, again it must be remembered that greatest instrument is construed in the light of the contemporaneous history and existing conditions at its formation and adoption. “That which it meant when adopted it means now,” said the Supreme Court in Scott vs. Sanford, 19 Howard, 426, a rule followed universally. (See, among many, Missouri vs. Illinois, 180 U. S. 219; In re Debts, 158 U. S. 591; S. C. vs. U. S., 199, U. S. 450.)

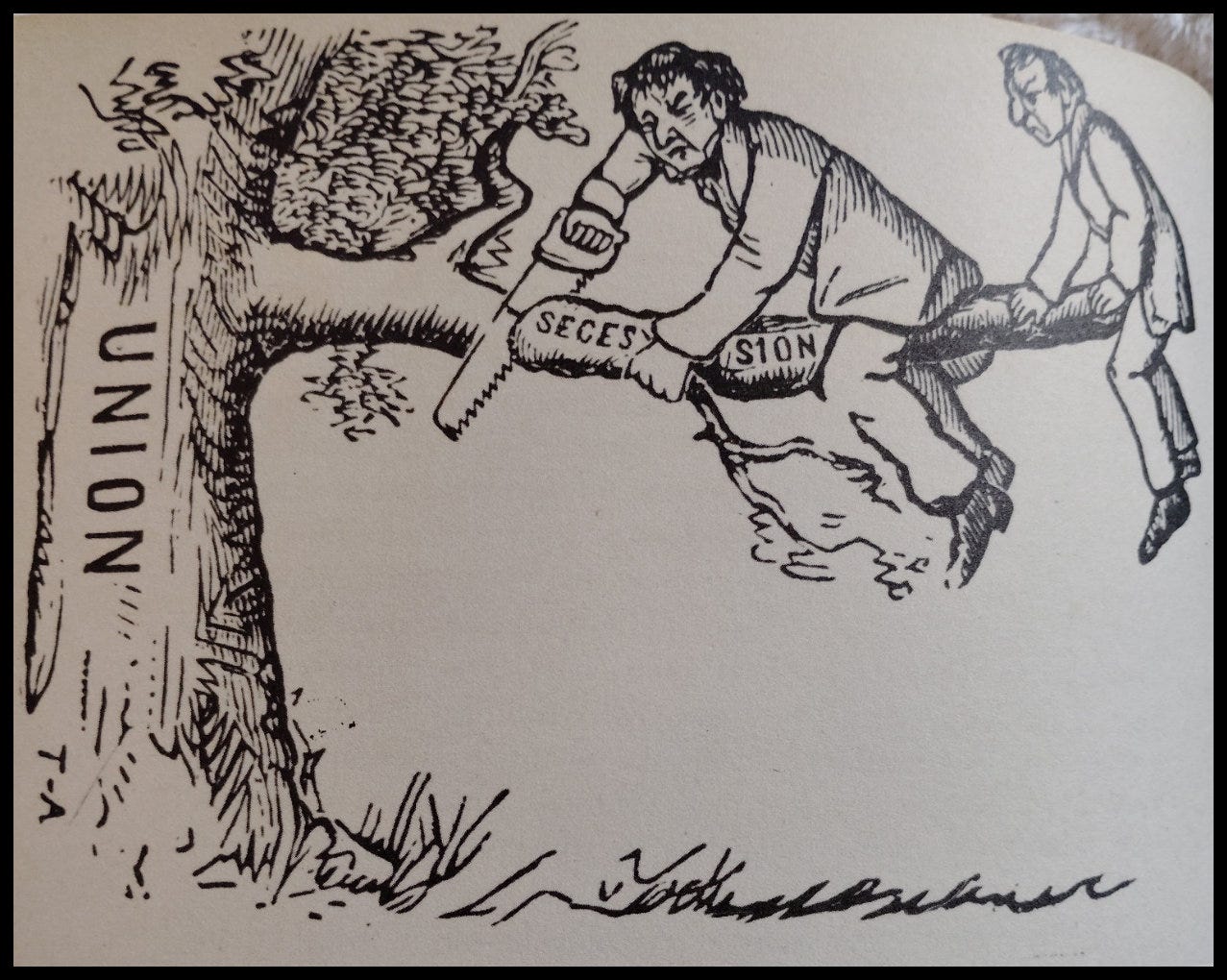

Aside from its practical bearing upon the problems which arise today and those which will press for solution tomorrow, here is the bearing of all this upon the historical interpretation of secession: If the delegated powers of the Federal Government are perverted by those exercising them, or misused or non-used, or powers not granted are assumed, persistently, endangering the domestic peace of a State, and this condition is backed and encouraged by a great bulk of opinion in other States and aided and abetted by laws of those other States, what is to be done by the suffering State? What would have been the answer to this question by any States, North or South, at the formation of the United States?

Grant that such a condition will rise again, where will we be? Such a condition existing, there remains the sovereign powers of the State, the admittedly undelegated and inherent sovereignty, having all the machinery of local government adequate when not obstructed for the protection of the domestic peace, for the defense of the property and lives of it citizens, endowed with all the functions essential to separate and independent existence, and therefore equipped, therefore endowed, mind you, under and pursuant to the Constitution, according to the fundamental law. Fundamental law because constitutionally recognized and guaranteed, notwithstanding the inherent and reserved powers of each State are not derived from the Constitution. In the light of the contemporaneous history and existing conditions, to this question what would have been the answer of the people of any State when they insisted ratification upon and obtained the Tenth Amendment: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to that State, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

The answer must be that each State would have said that thus guarded the Constitution left to it, in the event of the conditions which I have assumed, by the right to defend the admitted inherent sovereignty by any means adequate for that purpose. “The Constitution is a written instrument. As such, its meaning does not alter. That it meant when adopted, it means now.”

“The Constitution is to be interpreted by what was the condition of the parties to it when it was formed, by their objects and purposes in forming it, and by the actual recognition in it of the dissimilar institutions of the States.”

There is another fundamental rule followed in the interpretation of the Constitution, and that is that light is found in declarations by the States when ratifying that instrument, in imparting to the United States the breath of life for which it would never have had but for the action of three-fourths of the States concerned. So also, we go to the debates of the ratifying conventions and “to the views of those who adopted the Constitution” and get all the light possible from contemporaneous history and existing conditions. (For leading authorities see 4 Ency. U. S. Court Reports, pages 36 and 41.) One great mistake too many make in examining the legal justification of secession is to see it too exclusively in the light of today and under brighter conditions subsequent to that war. Such an error is fatal to a just estimate of secession. The question is: Did the States think they were getting into “an entangling alliance” from which, come whatever regret might befall, could they not withdraw? Does the light from ratifying conventions, the views of those who ratified the Constitution, and the weight of contemporary history indicate that the States meant forever to surrender for whatever domestic evil might result in some of their most important attributes of sovereignty? I don’t see how any open-minded and sincere person can in the light of the great bulk of evidence on which these questions relating to the formation and vitalization of the United States believe that under any interpretation of the Constitution, that instrument was meant to take from the States or from a State forever, the invaluable right of resuming the delegated sovereignty when in the wisdom of the people of a State such redemption (that is, secession) appeared necessary for domestic peace and to protect and make effective the undelegated sovereignty. Justice Catron, of the Supreme Court of the United States, quoting from the famous Federalist “in favor of State power,” said:

“These remarks were made to quiet the fears of the people and to clear up doubts on the meaning of the Constitution then before them for adoption by the State convention.” (License Cases, 5 Howard, 607.)

The great amount of people of the then several independent States were afraid of the centralized power about to be loaned to the United States government; and the right to resume delegated powers should the experiment become unfortunate was the great reason which brought the States to embark upon the venture. They were certain they had fixed the fundamental documents so that they might legally, constitutionally, and morally rightly get out if any State so desired. Some of the ratifying conventions sought to make assurance especially certain, Virginia, for instance, interpreting the Constitution as part of her ratification, said:

“The powers granted under the Constitution…may be resumed by the people…whenever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression.”

New York, followed by Rhode Island, as part of the res gestae, with reference to the powers delegated to the Federal Government, said that “the powers of government may be resumed by the people whenever it shall become necessary to their happiness.”

Applying with such evidence a proper reasoning deductible from the general nature of sovereignty, it follows that the existence of a sovereignty “endowed with all the functions essential to separate and independent existence.” Must have the attribute of self-defense. That is not sovereignty which has not the right of self-preservation. Sovereignty without the right of self-determined existence is unthinkable. Sovereignty must be dignified by all that the word implies. “As men whose intentions require no concealment generally employ the words which most directly and aptly express the ideas they intend to convey, the enlightened patriots who framed our Constitution, and the people who adopted it, must be understood to have intended what they have said,” correctly said Chief Justice Marshall in Gibbons vs. Ogden (9 Wheaton, 188. See also Kidd vs. Pearson, 128 U. S., 203 U. S. 16.) There can be no such thing as limited sovereignty. There is a division of sovereign powers; and that is the condition under and virtue of the Constitution in this country. But sovereignty is a self-explanatory word and meant at secession exactly what it meant at the adoption of the Constitution.

Shortly before leaving the bench in 1915, Mr. Justice Hughes of New York prepared the opinion in Kentucky vs. Becker (241 U. S. 563), and therefore, prepared this opinion which was subsequently adopted and delivered by Chief Justice White as the unanimous opinion of the Supreme Court. Concerning the power of the State of New York to control lands which were subject of a treaty between Robert Morris and the Seneca Nation of Indians in 1797, the court says:

“But the existence of the sovereignty of the State was well understood, and this conception involved all that was necessarily implied in that sovereignty, whether appreciated or not.”

Upon that impregnable position stood each seceding State in 1861.

In the South, we are coming too much to whisper that “our fathers did their duty as they saw it.” We should be calling for the world from the housetop that our Confederate fathers were right. For historical truth we should speak directly in the schools and should sound the facts in trumpet blasts wherever the subject of secession is under consideration. We should let the world know that those fathers are entitled to as much glory for the defense of their wives, their mothers, their children, and the domestic peace of their States by wielding the inherent sovereignty to recall the delegated sovereignty against a European foe, a defense which the South rendered gladly in our war with Spain, for which the right of local self-government might not perish from this earth; “to insure domestic tranquility,” one of the five reasons assigned in the preamble as the grounds for the establishment of the Constitution of the United States—to better safeguard the lives of the women and children of the South; to avert a destruction of some of the State’s most important inherent powers of sovereignty—in short, to escape imminent disaster involving the most vital human rights, the seceding States faced one or two courses of action, short of the most servile submission to the greatest of wrongs. They must either withdraw from the Union or remain in the Union and resort to armed force against Northern States and the Federal Government. But the situation at that time can be appreciated when we consider the constitutional facts here briefly outlined in the immediate light of what constituted the imminent disaster, the ominous peril which shrouded the South in increasing gloom. There is not enough space here, unfortunately, to discuss those powerful causes of that secession. Those causes are too inadequately presented in textbooks and too little taught even in the Southern schools. The production of this work, however, by the Sons of Confederate Veterans is one among other joyful signs there is a revival in the interest of historical truth. The truth and the whole truth is the battle cry of the great organizations of which whose leaders cry from their souls of sincerity and without the least thought or purpose of animosity or bitterness. In the interest of history, children need to be taught something about the great war which followed secession, and to be just to their Confederate ancestors they must have a fuller understanding of fundamental legal grounds of secession and that of the weighty causes which moved the South—not that she believed in secession alone at will but solely faced as an extreme measure—to resume certainly de facto and sovereignty delegated to the United States.

When the causes of secession are considered in the light of constitutional fundamentals herein outlined, we more readily avoid the illogical contention sometimes met which insists “that the result of war settled the question against secessionists.” It is obvious that war settled no great question. Didn’t the better thinking part of the world gladly agree to reverse the decision of a great question Germany thought she had settled forever by a decisive war? And didn’t the reversal of the work of gory, cruel brute force restore to wronged and outraged France suffering Alsace-Lorraine? America justly poured out her blood and lavished her gold in that great war just closing to help establish for the benefit of all people the principles upon which rest our separation from Great Britian and the de facto secession of the Southern States; the inalienable right of a people to break away from an objectional and hurtful government.

There will never be another Southern secession. Nobody thinks of it as a remedy for anything now, and no part of the Union will dare repeat the Northern nullification of the Constitution to avoid the evils of which—and not to destroy the Union and not to protect or perpetuate slavery—secession became the remedy to preserve the sacred binding power of a written Constitution without which the Union perishes certainly. And, again, because the Federal Government will never be again as limp and spineless and complacent in defending the South against such evils as nullification and other wrongs by Northern States and some Northern people, to escape all of which our fathers found secession the one probably bloodless remedy, justified by fundamental constitutional law, and invariable remedy with honor.

Forgive the length of my reply. This subject stirs in me not just deep conviction, but a profound sense of historical clarity.

Your article rightly asserts that Southern secession in 1861 was rooted in constitutional principle. But what you present—artfully, and perhaps cautiously—as a bold and controversial opinion is, in truth, a legal and historical reality. One that has been systematically buried beneath generations of political mythology and moral oversimplification.

Let’s be clear: The Southern states had every right—legal, constitutional, historical, and moral—to withdraw from the Union. The argument against their right was not rooted in law. It was rooted in politics. And Lincoln’s refusal to recognize that right was not a defense of constitutional order. It was the violent denial of it. As I've grown more knowledgeable throughout my life, perhaps nothing has tainted the reputation of Lincoln for me more than his stubborn insistence that the Union was meant to be perpetual.

The Union was formed through the voluntary ratification of the Constitution by sovereign states. It was a compact among equals, not a contract of submission. States like Virginia and New York made this explicit in their ratification documents, reserving the right to resume delegated powers if the federal government became abusive or oppressive.

To claim that states could enter but not leave is to fundamentally rewrite the logic of American self-government. If a people have the right to consent to a union, they necessarily have the right to withdraw that consent. Otherwise, the Union is not a republic. It is a prison.

The federal government derives all its authority from the Constitution. It has no inherent sovereignty. Its powers are enumerated, delegated, and limited. When that delegation is abused, when the government ceases to represent the interests of its constituent states, those states have the right to reclaim their original sovereignty.

This is not radical. It is foundational.

The Tenth Amendment, the structure of the Constitution, and the writings of the Founders all affirm this principle. Secession was not rebellion. It was a lawful, reasoned, and democratic assertion of political independence. It was no different in principle from the American colonies separating from Britain.

Lincoln’s claim that the Union was perpetual had no basis in the Constitution. It was his own interpretation, formed out of political necessity, not constitutional truth. The courts had never ruled on secession. Congress had never outlawed it. And no clause in the Constitution prohibits a state from withdrawing.

So when Lincoln sent troops to suppress secession, he was not enforcing the law. He was declaring war on a political doctrine he disagreed with.

He chose force over dialogue. He chose invasion over negotiation.

And in doing so, he shattered the very constitutional order he claimed to be preserving.

In the article, you gesture toward the legality of secession but then back away from the moral implications of what followed. I understand why you did so.

But, as a commentor and not the author, I will say it plainly: the war waged against the South was not only unconstitutional, it was unjust.

The South seceded peacefully, through legislative conventions, popular votes, and official declarations. It asked to be left alone. It formed a new government, sent emissaries to Washington, and sought a peaceful separation.

Lincoln refused. He initiated war to prevent it.

He did not act to “preserve the Union” so much as to preserve federal control over a region that had chosen, by every right, to govern itself. In doing so, he sanctioned a war that killed three-quarters of a million Americans and permanently redefined the relationship between the states and the federal government—not through consent, but through conquest.

Let us not confuse historical revisionism with fact. Lincoln himself said repeatedly that the war was not about ending slavery. In his letter to Horace Greeley, he said if he could save the Union without freeing a single slave, he would do it. The Emancipation Proclamation didn’t apply to slave states that remained in the Union.

The war was about power—centralized federal power versus state sovereignty. Slavery was a factor, yes, but not the cause of war. It became the moral banner only after the fact, used to justify the bloodshed and recast Lincoln as a messianic liberator instead of a constitutional aggressor.

The Southern states did not secede because they hated the Union. They seceded because the Union had ceased to respect their rights. Tariff policy bled their economy. Radical Republicans made clear that their institutions and way of life were under siege. And Lincoln’s election, without a single electoral vote from the South, made one thing unmistakable: the South had lost all political leverage within the system.

The Southern states chose independence over submission. They chose self-government over domination.

And for that choice, they were invaded, vilified, and nearly destroyed.

You end the article by invoking a hope that young Southerners remember the legal basis of secession. On that, we agree. But I would argue that we must go further.

They must also be taught that the war waged against that right was neither noble nor necessary. It was the death knell of the republic the Founders envisioned—a republic of consent, restraint, and limited power.

Secession was not a failure of American principles. It was their final defense.

And in crushing it, Lincoln and the post-war federal government replaced a constitutional Union with an indivisible empire.

The South was right. Constitutionally. Morally. Historically.

Those of us who say the South was right are often dismissed or denounced—but the arguments stand, plain and unflinching, for anyone willing to confront the facts. Yes, slavery casts a long shadow. And rightly so. It was a moral failing—not only of the South, but of the entire Union, North included, which protected, permitted, and profited from it for decades. What we now condemn was then legal, constitutional, and embedded across the American landscape.

But we must be clear: the war was not waged to end slavery. It was waged to prevent secession. Lincoln said as much—again and again. His letters, his policies, his own words make that undeniable. The Emancipation Proclamation itself carved out exceptions for Union-held slave states, proving it was a political tactic, not a moral crusade.

Remove slavery from the equation—as Lincoln himself often did—and what remains is a constitutional crisis, resolved not by law or debate, but by invasion and conquest.

Once that truth is recognized, one conclusion becomes inescapable: the South was right—constitutionally, philosophically, and historically. Lincoln was wrong—not merely in execution, but in principle. And the nation he forged from the wreckage of that war bears little resemblance to the republic the Founders envisioned: a Union of consent, not coercion.

Great work! It is on the back of State sovereignty that any righting of the ship of our Nation will float or sink. While I hope and pray for the President and his administration I do not think the remedy to the overwhelming problems that we face are not found in executive orders , which I have never fan of. The only remedy is found in the States returning their rightful position and roll in our nation’s life.