Fort Sumter and the War Conspiracy

Deo Vindice (As God as (our) Defender) Confederate States of America's motto

The Civil War which began in the 1830’s as a cold war and moved towards the inevitable conflict somewhere between 1850 and 1860, was one of America’s greatest emotional experiences, and still is today over one hundred and sixty-four years ago. When the war finally broke in 1861, beliefs and political ideals had become so firm threat they transcended family ties and bonds of friendships—brother against brother. The story of this supreme test of our Nation, through one of utmost tragedies our country has ever seen.

“What passes as standard American history is really Yankee history written by New Englanders or their puppets to glorify Yankee heroes and ideals.” ~D. Grady McWhiney

Before a tyrannical government can conduct a campaign of genocide against an enemy, it must first convince its people and the people of the world that the targeted group is evil, dangerous, sub-human folks outside the norms of “politically correct” society. Once the targeted group is thus slandered and socially stigmatized, it becomes acceptable, even necessary to rid society of such “evil” and “hateful” folks. Lincoln’s campaign proved it could be done.

Fort Sumter and the War Conspiracy

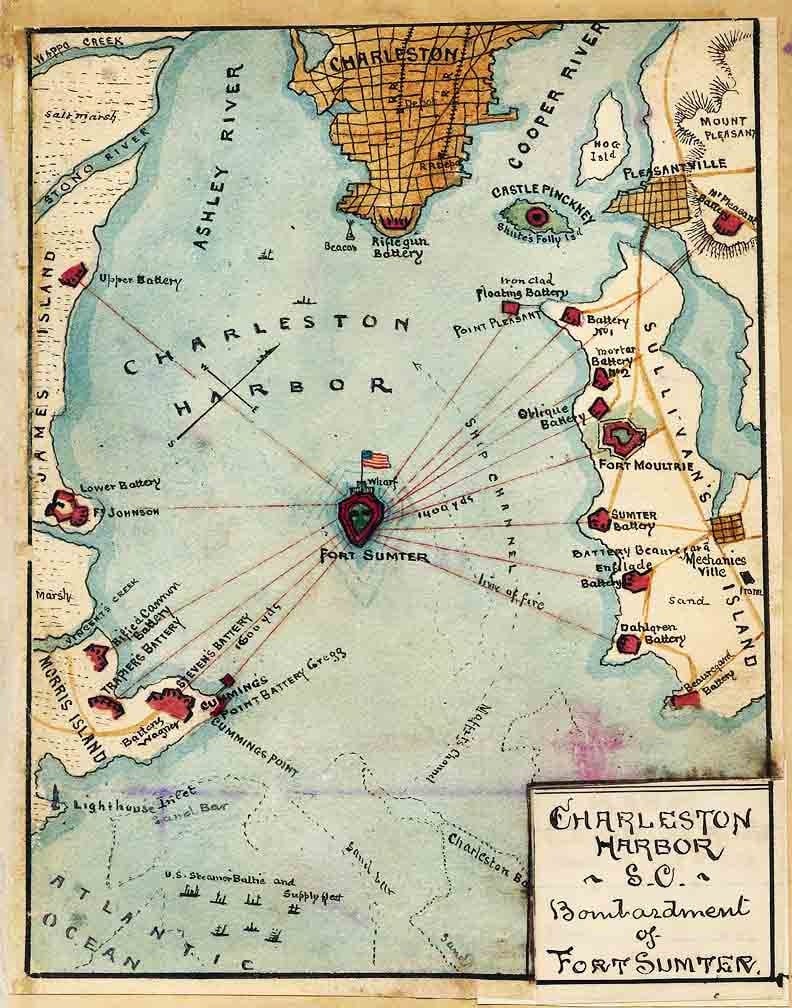

Who started the Civil War in 1861? Many high school texts book declare that the South started the war by firing on the American flag at Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Abraham Lincoln often referred to the South as having started the war as in his December 6, 1864, address to Congress:

“I mean simply to say that the war will cease whenever it shall have ceased on the part of those who began it.”

The beginning of the War Between the States is wrapped in Union propaganda justifying the war. There was so much more to it than Confederate guns firing on the Union held fort in Charleston harbor. It is a story filled with intrigue, secret orders, political deception, and conspiracy.

The election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States in November 1860 set off a series of state secession conventions that resulted in seven states leaving the Union by his inauguration on March 4, 1861. These Confederate states, even volatile South Carolina, hoped to leave the Union in peace. The desire for a peaceful separation was so central that it was specifically included in Section 2, Article VI, of the Confederate Constitution:

“The Government…hereby declares it to be their wish and earnest desire to adjust everything pertaining to the common property, common liability, and common obligations of that Union upon principles of right, justice, equity, and good faith.”

In late 1860, most of the people of the North believed that secession was a natural right based on the consent of governed and that the Southern states should be allowed to secede peacefully. Historian Howard Cecil Perkins compiled 495 Northern newspaper editorials dated from late 1860 to mid-1861 and concluded that the great majority of them assumed secession was a constitutional right and opposed the use of force against seceding states. The Bangor Daily Union stated on November 12, 1860, that:

“Union depends for its continuance on free and will of the sovereign people of each state, and that consent and will is withdrawn on either part, the Union is gone. A state coerced to remain in the Union is ‘a subject province’ and can never be co-equal member of the American Union.”

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Nelson of New York after studying the President’s war powers reported to Secretary of State William Seward that the President could not use coercion against states without serious violation of both the Constitution and statutory law.

Of particular immediate concern for peaceful separation was the disposition of several coastal forts, the most important of which were Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor and Fort Pickens near Pensacola. In that regard, on December 9, eleven days before the South Carolina Secession Ordinance, South Carolina Congressmen met with President Buchanan on the Fort Sumter issue. At that meeting there was an informal agreement that Forts Moultrie and Sumter in Charleston would not be attacked by South Carolina forces so long as they were not reinforced and did not act aggressively towards South Carolina.

On December 12, seven weeks after the inauguration, Lincoln sent E.B. Washburne to Army Chief Winfield Scott with instructions to prepare to hold or retake the forts after his inauguration on March 4th. The Commander of the Union garrison in Charleston, Major Robert Anderson, at that time was situated at Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter was unoccupied except for construction crews. Following the December 20 secession of South Carolina, feeling that Fort Moultrie was too vulnerable to attack from shore, on the night of December 26th, Anderson moved his eighty-two men to Fort Sumter in the middle of the day. This caused a stir in both Charleston and Washington. South Carolina regarded the move suspiciously and several of President Buchanan’s cabinet members felt the move violated their informal agreement with South Carolina. In fact, the Secretary of War Floyd of Virginia resigned over the matter. Major Robert Anderson, however, had made the move on his own initiative.

Shortly after his move to Fort Sumter, Anderson reported to Army Headquarters in Washington that he had four months’ provisions, enough to last until around April 26th. A few days later, he wrote to a trusted friend in Charleston that he actually acquired five months’ supplies, enough to last until around May 29th. The Charleston authorities also allowed Anderson to continue purchasing provisions in Charleston. Meanwhile on December 31st, General Winfield Scott secretly and unbeknown to President Buchanan, had the Navy ship, Brooklyn, outfitted to supply and reinforce either Fort Sumter or Fort Pickens. Besides supplies and ammunition, it was to carry 200 artillery soldiers under Army Captain Vogdes.

Also, under orders from General Scott, a merchant steamer, The Star of the West, left the Norfolk area on January 7, with supplies for Fort Sumter. It concealed 200 troops below deck. On arriving in the Charleston harbor two days later making for Fort Sumter, the Charleston batteries fired a warning shot across her bow. She kept coming, but after the Charleston batteries began to fire in earnest, she turned away. This incident was an embarrassment to the Buchanan administration, who hoped to avoid war and keep faith with the South.

On January 10, Florida seceded. That night the Union Commander at Fort Barrancas on Pensacola Bay moved his men during the night to the larger facility of Fort Pickens. On January 21st, the Brooklyn, carrying Army Captain Israel Vogdes and his artillery reinforcements arrived at Pensacola and was joined by the Sabine and Wyandotte. Following some tension and negotiations with Confederate civil authorities and General Braxton Bragg on January 29, an Armistice was signed by Union Secretary of War Joseph Holt and Navy Secretary Isaac Toucey, agreeing that Fort Pickens would not be attacked unless reinforced or engaged in aggression against Confederate forces in the area.

Back in Washington on February 7th, retired Navy Captain Gustavas Vasa Fox presented an aggressive plan using supporting warships to General Scott and Secretary of War Holt to reinforce Fort Sumter. The next day President Buchanan doused the plan. The cabinet agreed that reinforcing Fort Sumter or Fort Pickens was an act of war and would be likewise interpreted by the South. Unexpectedly, on February 25th, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed three high ranking Peace Commissioners to go to Washington for the purpose of negotiating the disposition of Forts Sumter and Pickens and other issues.

President Davis also assigned Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard as Confederate Commander in Charleston on March 3rd. Beauregard had been a student of Robert Anderson at West Point, and the two men were close friends. Anderson was himself a Southern from Kentucky, married to a Georgia girl. Major Anderson was a loyal Unionist, but he did not want war.

Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4th, promising to collect the tariff regardless of secession. It was also evident that unlike all his predecessors and most Americans, he did not regard secession as legal, and he was willing to use military force to prevent the states from leaving the Union. He would not see the Confederate Peace Commissioners. They were, however, able to negotiate indirectly through Supreme Court Justices John A. Campbell and Samuel Nelson, who had volunteered to interposition with Secretary of State William Seward for the cause of peace. Seward continuously promised them that Fort Sumter would be evacuated.

On March 9th, Lincoln proposed to his Cabinet that Fort Sumter be reinforced. Only two supported him in this. They thought it would mean war could possibly end in a military and naval disaster. Somewhat surprisingly, since he had secretly been doing Lincoln’s bidding since the inauguration, General Scott, who was a Virginian and who did not want war, was the plan’s most vocal opponent. He believed it would take a force of at least 20,000 men, and no such force was now available. The Navy men would not come under fire for long.

General Scott, however, on March 12, ordered the reinforcement of Fort Pickens in Florida. Lincoln again polled his cabinet on March 15 with negative results. Captain Fox was sent on a special mission to see Major Anderson and South Carolina Governor Francis Wilkinson Pickens on March 21 to assess the possibilities. On March 29 Lincoln’s Cabinet was finally persuaded to approve Lincoln’s plan to reinforce Fort Sumter, although they knew it meant war.

Many Northern businessmen were now reassessing their positions on secession. They began to realize that a free trade South would take business away from a high tariff North. They also realized they would lose their principal source of tax revenue. More Northern newspapers began to reflect a distaste for secession.

There were also serious talks of California and Oregon seceding to form a Pacific nation. Democratic controlled New Jersey was also considering secession to escape Republican dominance. New York City was sympathetic to the South and was considering secession to become a free trade zone. Lincoln believed a brief war was necessary to put down the Southern rebellion and to discourage others from the same path. But the general public consensus in the North was that they did were unfavorable to war.

On April 1, Lincoln issued six different secret orders directly to various naval personnel without consulting Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles or Secretary of War Simon Cameron. All pertained to outfitting and manning the Powhatan, one of the Navy’s fastest and most heavily armed ships for a secret mission to Fort Pickens in Florida. The most unusual was direct to Navy Captain David Dixon Porter to relieve Captain Samuel Mercer and take command of the Powhatan.

Meanwhile on April 1, Army Captain Vogdes finally delivered the March order from General Scott to reinforce Fort Pickens to the squadron commander at Pensacola, Navy Captain H.A. Adams. Adams, however, refused to comply, since it would violate Armistice and mean war. Instead, on April 6, he sent a letter to Navy Secretary Gideon Welles to authenticate the orders. Adams received orders from Welles confirming that Fort Pickens must be reinforced immediately on the 12th. By this time the Pensacola Bay flying under British colors, the Powhatan, under the command of Captain Porter. Under cover of night, they succeeded in reinforcing Fort Pickens without a fight. They were unaware of developments at Sumter. Confederate General Bragg took no immediate action as the Confederate government was still hoping for peace.

Major Anderson received notification on April 4th that a reinforcement expedition should arrive in Charleston by the 15th. He and his officers did not regard it as a happy prospect. Like General Scott, they believed that reinforcement could not occur without a Union army of 20,000 men first taking Charleston and its batteries from behind.

On April 6, Lincoln gave the final order for reinforcing Fort Sumter. Three warships, the Pocahontas, the Pawnee, and the Harriet Lane were assigned to the task force commanded by Captain Scott aboard the steamer Baltic, which would carry 200 soldiers. The Powhatan (that Lincoln had sent to Pensacola) was also listed as part of the task force.

The Confederate Peace Commission was still in Washington on April 7th listening to Secretary of State William H. Seward’s promise the Sumter would be evacuated. But they had grown suspicious of all the activity of the last weeks and had surmised that a battle fleet was on its way to reinforce Fort Sumter.

South Carolina Governor Pickens received an envoy from Washington on April 8th with a message announcing:

“I am directed by the President of the United States to notify you to except an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only, and that if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, and ammunition, will be made without further notice, or in case of an attack on the fort.”

Governor Israel Pickens passed the unsigned communication to President Davis and his Cabinet in Mongomery, Alabama.

In the meantime, Lincoln had planted in the Northern press, the misinformation that the garrison at Fort Sumter was starving and in desperate need of provisions. Judging from his communications in December, Anderson probably had anywhere from two to six weeks provisions in store, not counting the provisions the Confederates had allowed to be purchased in Charleston up until April 7th.

President Jefferson Davis knew all along that Lincoln was maneuvering to get the South to fire the first shot. But Davis knew that legally the aggressor in war and other laws is not the first to use force, but to render force necessary. Davis also recognized that Lincoln did not care about legal technicalities. He was maneuvering for the favor of the Northern public’s support and opinion, which he would need behind him to successfully wage a short war to put down the Confederacy. Lincoln’s public relations pitch would be that the Confederates fired first on the flag to prevent starving men from receiving provisions.

Realizing that the Union fleet was already nearing Charleston and not wanting to risk the prospect of fighting the fort and a Union war flotilla at the same time, Beauregard sent former Senator and now Colonel James Chestnut and Captain Stephen D. Lee on April 9th to demand surrender of the fort and evacuation of Federal troops. Anderson indicated that it was his honor to resist, but that he would be starved out in a matter of days anyway.

This message was sent back to Montgomery. An offer was made to Major Anderson to let him choose the day of evacuation at which time he and his men could salute their colors. Anderson named the 15th, probably based on Captain Fox’s promise of reinforcement by that date. By April 11th, however, warships of the Union reinforcement squadron could be seen within striking distance of Fort Sumter and Charleston. At 3:20 am on the 12th, Beauregard sent messages to announce that the fort would be bombarded within one hour. At 4:30 am the Confederate batteries encircling Fort Sumter commenced its bombardment.

The outline of the dark harbor was dotted with a line of twinkling lights while bursting shells illuminated the sky above. Fort Sumter did not begin to return fire for two hours. Although the Union flotilla could be seen from Sumter and Charleston, they did not engage the Confederate guns and held their distance.

The Union Naval Commander Captain Fox arrived on the Baltic and boarded the Pawnee. The captain of that ship, the senior officer of the task force except Fox, however, refused to engage the Charleston batteries or move to support Fort Sumter, telling Captain G.F. Fox that his sealed orders stated specifically to wait for the arrival of the Powhatan before initiating the reinforcement action, which he knew meant inaugurating war. This was a shock to Fox as he had been led to believe by the Secretary of War that the Captain of the Pawnee would have orders to allow his entire force to open passage to Sumter if needed. The Powhatan was at that very moment at Fort Pickens under secret orders from Lincoln. The warship Pocahontas arrived early on the 13th.

At about 7:30 am on the morning of April 13, seeing that the fort was on fire, the Confederates stopped firing and offered the use of a small fire engine to contain the fire, which may have threatened the fort’s ammunition and powder supplies. Although his men were having to stay low to the ground and breathing through wet handkerchiefs to deal with the smoke, Anderson refused the help, saying the fire was almost burned out. Later a shell knocked down the flag, and bombardment ceased, the Confederate commanders thinking surrender was imminent. The flag was quickly replaced by a Union sergeant, to the cheers of the Confederates, who expressed constant admiration for their brave and embattled enemies, many of whom were personally known to them. At about 2:00 pm in the afternoon a white flag was displayed, and nearly thirty-four hours of bombardment ended.

Amazingly, there were no casualties on either side. Beauregard allowed the gallant defenders of Fort Sumter to assemble and salute their flag before being picked up by a transport and delivered to the Union flotilla just outside the Charleston bar. Unfortunately, while Anderson was firing a fifty-gun salute to his flag, and ember fell into some powder and one man was killed and five injured. In a show of respect for the weary defenders of Fort Sumter, Confederate soldiers lined the beaches and removed their caps in salute as a steamer silently passed out of the harbor to the Union Navy expeditionary force.

Lincoln had achieved what he wanted. The news of Confederate firing on the flag at Fort Sumter and its “half-starved” defenders rallied the North. In a May letter to Captain Fox, Lincoln said,

“You and I both anticipated the cause of the country would be advanced by making the attempt to provision Fort Sumter, even if it should fail; and it is no small consolation now to feel that our anticipation is justified by the result.”

That result was the rallying of Northern patriotism and war fever to punish the South for firing on Fort Sumter. The Confederates had been placed in a position of either firing the first shot or risking the loss of Charleston and the credibility of Confederate resistance to Northern coercion. President Jefferson Davis shouldered that responsibility in his statement to his cabinet:

“The order for the sending of the fleet was a declaration of war. The responsibility is on their shoulders, not on ours. The juggle for position as to who shall fire the first shot in such an hour is unworthy of a great people and their cause. A deadly weapon had been aimed at our heart. Only a fool would wait until the first shot has been fired. The assault had been made. It is of no importance who shall strike the first blow or fire the first gun.”

General P.T.G. Beauregard had the Confederate Stars and Bars raised over Fort Sumter on April 14th to the salute of Confederate guns raising the harbor. The next day Lincoln called on the state governors for 75,000 volunteers to put down the Southern rebellion.

Although Lincoln was successful in rallying Northen support by maneuvering the Confederates into firing on the flag at Fort Sumter, his call for troops to coerce Southern states back into the Union had a disastrous impact on the Border States. Union sentiment in those states quickly evaporated, and Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina seceded. Governor Ellis of North Carolina declared that his state would:

“I can be no party to this wicked violation of the laws of the country and to this war upon the liberties of a free people. You can get no troops from North Carolina.”

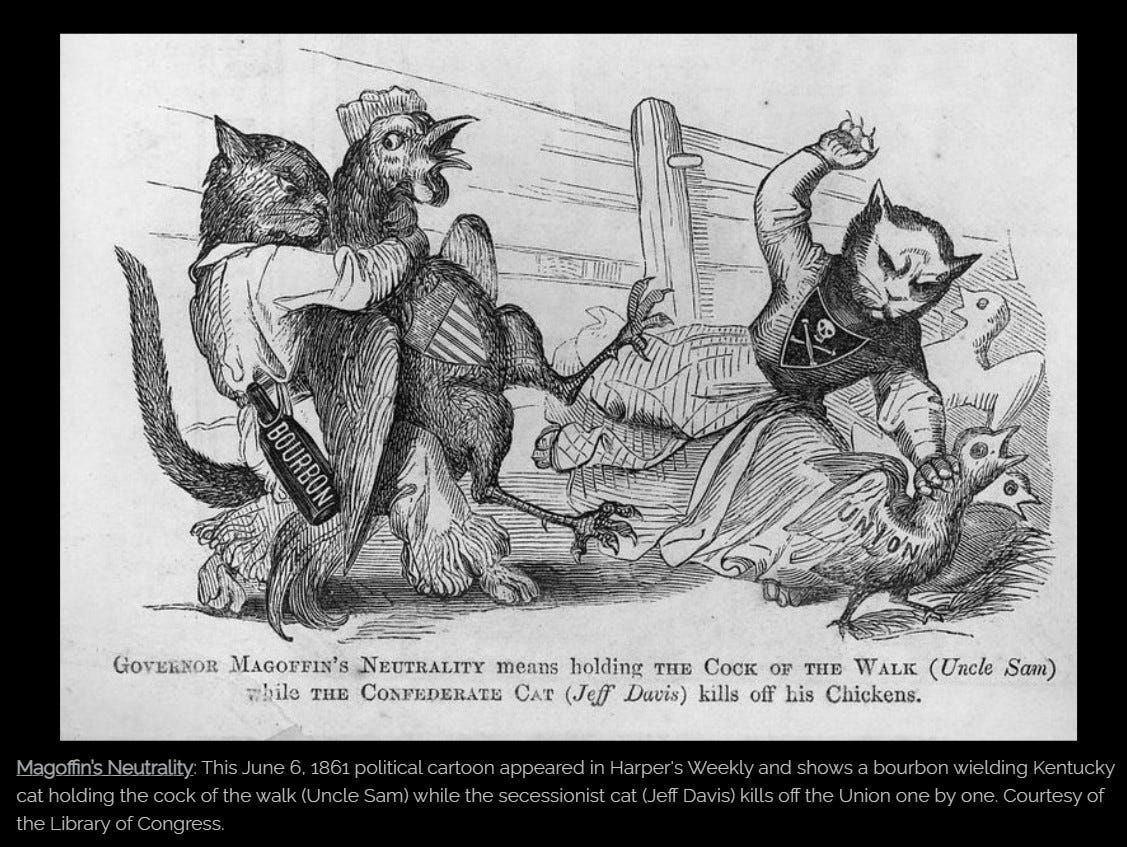

Lincoln was truly shocked when he received wires from the Governors of Kentucky and Missouri. Governor Beriah Magoffin of Kentucky replied that:

“I say emphatically Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern states.”

References for the Fort Sumter and the War Conspiracy:

The Civil War: a narrative, by Shelby Foote; 1958, 1986 editions

The American Iliad 1848-1877, 2002 edition, by Ludwell H. Johnson

Lincoln Takes Command: How Lincoln Got the War He Wanted, by John S. Tilley 1941, 1991 editions.

The Truth of the Conspiracy of 1861, by H.W. Johnstone, 1921 edition

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies and Navies

Moore’s Rebellion Record, published 1861

**Special thanks to the South Carolina Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans for the use of their library and materials.

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 – February 20, 1893) was an American military officer known as being the Confederate General who started the American Civil War at the battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is commonly referred to as P. G. T. Beauregard, but he rarely used his first name as an adult. He signed correspondence as G. T. Beauregard.

Thank you Monica for this in depth explanation of the events leading to the provocation at Fort Sumter. The explanations taught to me in public schools for the start of the war at Fort Sumter didn't make any sense to me, and started me down the path to find the truth.

I love this quote:

“What passes as standard American history is really Yankee history written by New Englanders or their puppets to glorify Yankee heroes and ideals.” ~D. Grady McWhiney

I toured Fort Pickens a few years back, it's a massive complex. The National Park Service openly admits it was built with slave labor. It seems the federal government had no problem using slave labor when it was to their benefit. Such hypocrisy!