The Little Town Ahead Called Gettysburg

A local story about John S. McCurry who would never return to his home in Diamond Hill, South Carolina

The Little Town Ahead Called Gettysburg.

A story about John S. McCurry who would never return home to his small town of Diamond Hill, South Carolina.

Abbeville was cast in a significant role at the beginning cue and at the closing of the curtain, In the greatest tragedy ever to hold our nation's historical stage. The War Between the States has been called the first modern war and the first Total War. Its battlefields and tactics have been studied by military historians and tacticians the world over. It killed and disabled more Americans than the total of all our other conflicts from the Revolutionary War up to World War I and World War II and the Korean conflict. Few persons could be found in Abbeville County, or in the old Confederate states whose ancestors to that era who did not have a near relative who either was killed, wounded, or served in that tragic conflict.

Abbeville district with an 1860 white population of 11,516 had 349 men killed in action. This did not include the wounded or those who died of disease. By comparison, Abbeville County with a 1940 population of 22,931 had 72 men killed in action during all of World War II.

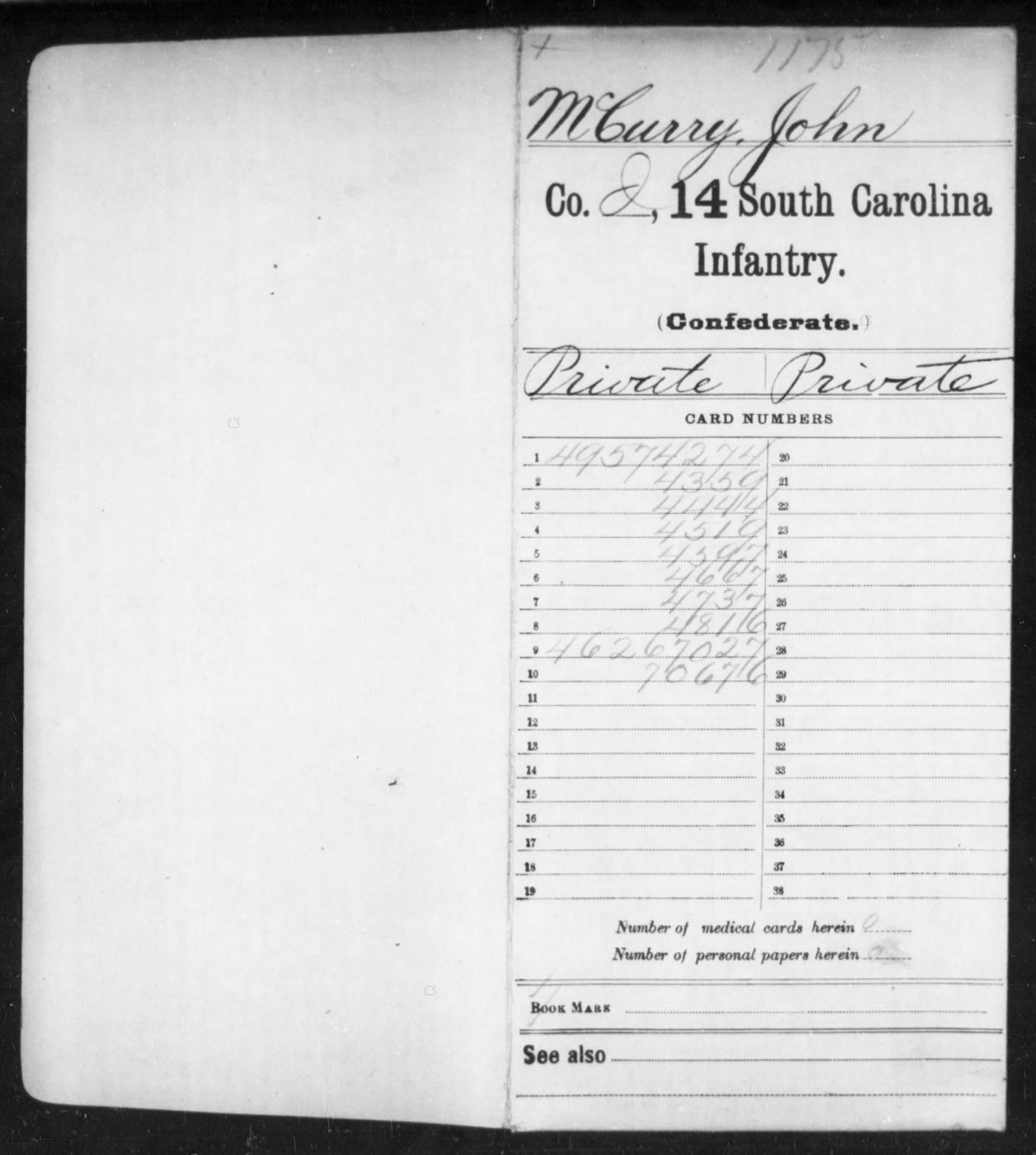

John S McCurry, John Whitfield McCurry and Augustus McCurry were cousins, who departed their home and way of life in Abbeville county's diamond hill community, to be cast in the role of Confederate soldiers. John Whitfield was the great-grandfather of Everett McCurry of the Cedar Springs Rd. Abbeville. John S. was the father of the writer’s grandmother and the late Mrs. Thomas Lester Ferguson, of Antreville.

The following is a brief narrative of the common soldier like John S. McCurry who served in the Confederate army, written from letters sent home to his wife, Nancy E. McMahan-McCurry.

It was a morning graced with a warm, clear, dawn which ushered in that fateful day of July 1st. The sun rose to the crest of the ridge, shedding its bright rays over a rolling terrain, thinly veiled in wisps of smoke and bejeweled in the morning’s dew. But the pleasantry of the elements and the beauty of the nature’s setting were little noted by John S. McCurry, Company I, 14th South Carolina Volunteers, McGowan’s Brigade. His thoughts were of his home in South Carolina, Abbeville County, the Diamond Hill community.

At home, there were his wife and his little daughter, Martha Melinda, now age four, whom he had seen last at age two. Another little daughter, John Anna, had not yet been born at the time of his departure. He was now far from Diamond Hill, well into his second year in the Confederate Army and deep in enemy territory. On this morning, the Brigade was “strung out.” The line of march was carrying them into the sun, along the Cashtown Road in Pennsylvania. Ahead, they said, was a little town called Gettysburg.

John S. McCurry was born to the Old South but not to the life of the southern gentry. His father, John McCurry, was a dirt farmer, and John S. had grown to manhood on his father's farm. Married at age eighteen, like his father, he grubbed out a living for his family on a small acreage of cotton and food crops.

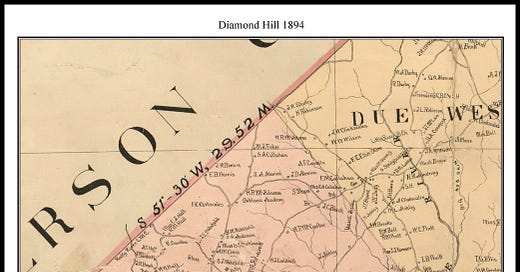

His world was his community with such places as Brownlee Crossroads, Bowen’s Crossroads, Rocky River, Spur Creek, Martin’s Mill, Black’s Mill, and the areas churches of Shiloh and Little Mountain. It was a close-knit community with kindred and neighborly ties. There were families of Blanchetts, Subers, Caldwells, Campbells, Canns, Grants, Hodges, Hamptons, McMahans, Fergusons, Flemings, Parkers, Pattersons, Simpsons, Sutherlands, Wakefields, and others.

Like his neighbors, John S. McCurry seldom left the confines of the community. The exception was an occasional wagon or horseback trip to Abbeville or Anderson, near twenty miles in either direction as necessity required. Not having the advantage of an education and being illiterate, John had little knowledge of and little interest in that world beyond his realm. His concern revolved around those conditions affecting his ability to provide for his family. His farm, with little exception, provided the family's food. With the money from his meager crops of cotton, he purchased the manufactured necessaries for his family and implements for his farm.

John S. McCurry, however, was not destined to remain unaffected by the troublesome issues building in that world beyond his quiet, rural community of Diamond Hill. The stories of war concerned him. The South was being made a stepchild. Northern politicians were forcing import duties on manufactured goods coming into the country. This would make those goods too expensive for Southern farmers to afford. The purpose, in all of this, he was told, was to force Southerners to buy their manufactured goods from Northerners. The goods would be priced extremely high, but the Southerners would pay very little for their cotton. Then there was the issues as to the slaves. These Blacks had been brought from Africa by Northern ship owners who sold them to the plantation masters. This issue was of less concern to John S. McCurry, because like the majority of his neighbors, who worked their own farms and applied their own trades, he owned no slaves. His only experience was seeing them on the wagons which passed by from the Brownlee, Bell, or the Clinkscales plantations. He felt no compassion for the slaves as they considered themselves better than many of the whites who did not own a plantation, generally referring to such whites as “po buckra.”

Northern politicians were in control in Washington with no regard for the best interest of the South. This word came to Diamond Hill with dire predictions. McCurry heard it from the political leaders, from the pulpit, and from the knowledgeable citizens of the community.

The upcoming Presidential election was a focal point. As Abraham Lincoln was elected, he was cast by area politicians as a foreshadower of those dire predictions. The only recourse to the South was to become an independent nation and to rid itself of northern interference. There was word of a meeting in Abbeville and soon the word that South Carolina had declared herself an independent Republic.

In the weeks that followed, the word continued to reach Diamond Hill to engender excitement. Fort Sumner had been captured, and other Southern states were uniting with South Carolina to form a Confederate States of America. There was also words that the North was raising troops to crush the South and was blockading Southern ports. Several of McCurry’s boyhood friends were already leaving the area to join, by now, the Confederate Army.

In June came the word that Confederate forces had swept the battlefield in Virginia at a place called Bull Run that the Federal troops had run all the way back to Washington. Southern patriotism reached a feverish pitch, and on September 3rd, John S. McCurry made his mark on the line. He departed the Diamond Hill community with a company raised by Henry H. Harper, son of a prominent Lowndesville family.

At Camp Butler, near Aiken, the company was mustered into the Confederate Army. Training followed at Light Knotwood Springs near Columbia and then for a brief time on the South Carolina coast.

Mid-winter 1862 found McCurry in Virginia. The Company was now being assigned to a regiment and to Gregg’s Brigade. McCurry found the Confederate Army a poor provider. The men suffered much from the cold, rain, and snow. Winter quarters were whatever the men could provide for themselves. Usually this consisted of a small log hut which six or eight men pooled their talents to build. Straw and mud were used to fill the space between the logs, and the hut was roofed with sod or a piece of canvas. The fireplace was fashioned with stone, mud, and sticks and was a constant fire hazard. Rations usually consisted of cornmeal and pork. Other foods, not issued on a regular basis, were flour, beef, field peas, Irish and sweet potatoes, rice, and molasses. Due partially to inadequate transportation, the rations were often in poor condition. The cornmeal and field peas were often weevil infested, the beef rank, and the pork rusty with the hair still on the skin.

Privates in the Confederate army did their own cooking. McCurry and three friends from families he had known back in Diamond Hill cooked together. They had no skillet but fried and boiled their rations in two halves of a captured Yankee canteen. They bake their potatoes in the ashes and glowing embers of their cooking fire.

With the coming of spring, conditions improved somewhat as the weather warmed up. Then, in May, John S. McCurry was treated to a pleasant surprise. Replacements were received in Company I, and among them were two cousins from home in Diamond Hill. These were John Whitfield McCurry, age 33, and his younger brother, Augustus S. McCurry, aged 18. John S. took them into his group to share the hut and the cooking. He gave them the benefit of his experiences in camp life, picket duty and contact with the enemy.

Camp rumor had it that the Yankee army, 100,000 strong, was massing for an attack on Richmond. Conversations in the ranks was that they would soon “see the monkey.” The McCurry cousins agreed to look for each other after each battle to give aid, if either of them were wounded, or to send word to the home folks, if killed.

The battles were not long delayed. With the Federal army within six to twelve miles of Richmond, General Robert E Lee ordered his army into the attack. The vicious fighting which followed came to be known as “The Battle of the Seven Days.” After the fighting at the little place called Cold Harbor, Augustus did not meet John S. and John Whit. As agreed, they searched. They found him among the dead and wounded who lay scattered in the wake of the battle. He had been shot through by a minnie ball. Captain Henry Harper, still commanding Company I, noted in his record, “Augustus McCurry, killed at ‘Coal’ Harbor, 27 June 1862.”

In the weeks and months which followed, the two surviving McCurry’s experienced much hard living and hard fighting. In desperate times the army was kept on the move day and night, trudging along roads saddened by heavy rains, snow or sleet. Duty was a hard taskmaster. Frequently, sick and half famished from exposure and poor rations, they plodded on. Time and again they formed for battle. Then, with the wave of the officer’s saber, the color bearer would go forward, holding the flag of the Confederacy aloft. Then to the piercing, tumultuous shrill of the “rebel yell,” the lines would sweep forward into the acrid smoke of battle.

The aftermath of battle was a fearsome sight with the dead and the wounded lying about the field over which the battle had swayed. As they marched away from one battlefield, Company I chanced to pass a small farmhouse which was used as an aid station. The ground about it lay littered with the wounded. From inside the structure, the McCurry’s could hear terrible screams. They knew the surgeons were at work. On the ground outside a window, they saw a pile of human parts—the bloody stumps of arms, legs, hands and feet.

In the course of marching and fighting, obtaining sufficient food and cooking was a desperate struggle. The McCurry’s, like their comrades in the ranks, suffered from being hungry much of the time. If flour were available, it was mixed with water, often muddy, to form a crude dough. This was wrapped around a stick or ramrod and browned over a fire. Cornmeal was mixed with water to form a pone and this was placed on a flat surface exposed to the fire until cooked. Any meat available was cooked on a stick over the fire. If a stray cow were found, it was milked. If they pass through a garden, any edible particles of vegetables were eaten, leaving nothing, “same as army worms,” as one Yankee described it after the hungry Confederates had left his garden. Sometimes mule meat was issued.

At times grains of corn were scratched from the dirt where animals had been fed. The grains were parched and eaten. This provided little nourishment, however, and caused the men's jaws and gums to ache with almost unbearable pain. On occasions, they obtained fish by grabbling in a nearby stream. They also forged the woods and fields for rabbits, squirrels, and other small game, and knocked birds from their roosts at night. The capture of Yankee supply wagons was an event of much anticipation. Once the McCurry’s were at the point where captured wagons had been set afire by the wagoner’s before leaving them. The wagons were found to be loaded with barrels of eggs packed in salt. The eggs which had been baked in the heat of the burning wagons were delicious and were ravenously eaten. Captured wagons had been found to contain unheard of luxuries such as oranges, lemons, oysters, sardines, nuts and candies. More often, however, they contained only hard crackers and pork, but to the McCurry’s and their fellow Confederates, this was like apple pie.

The clothing supplies for the Confederate rank and file were as deficient as their food. Many of the men marched barefoot, often leaving bloody smears from bleeding feet torn by the brambles or cracked from the bitter cold. As their desperate situation necessitated an opportunity permitted, shoes were taken from a captured Yankee or from one on the battlefield who no longer needed them. Some of the men yearned to go into battle in the hope of obtaining a wool blanket, perhaps an overcoat, or even a hat. A nutbrown jacket worn with the blue pants of Federal army issue and black broad brimmed hat became the somewhat common dress for the McCurry’s and the Confederate ranks in general.

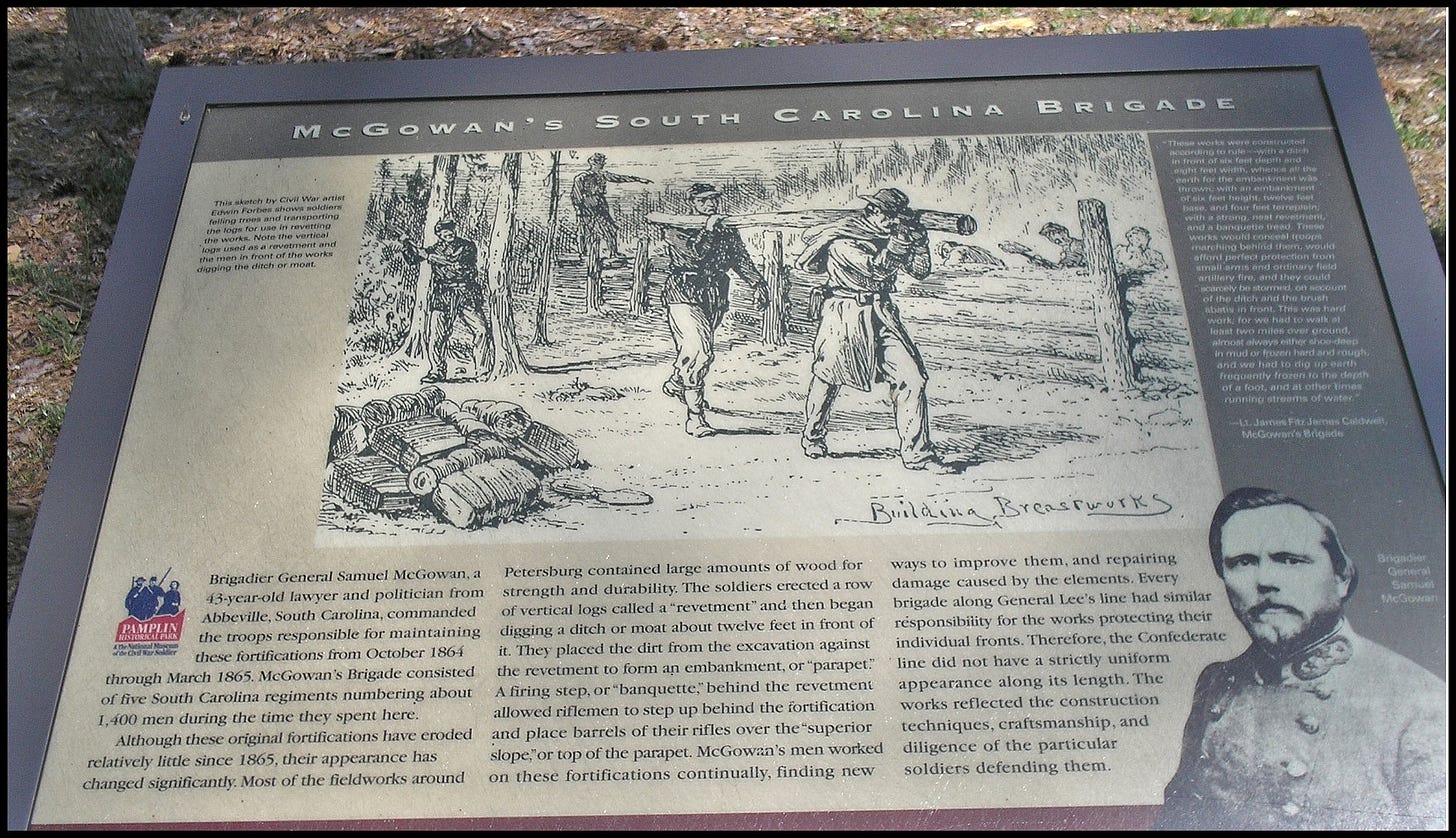

The McCurry’s were participants in hard fought battle of Chancellorsville in May of 1863. General Gregg, their former brigade commander, had been mortally wounded in the prior battle of Fredericksburg. Their regimental commander, Samuel McGowan, a noted lawyer from Abbeville, had been promoted to replace General Gregg. The brigade had become McGowan’s Brigade. Now, here at Chancellorsville, General McGowan was severely wounded; and Colonel Abner Perrin of Edgefield was placed in command of the Brigade. Colonel Joseph N. Brown of Anderson was now assigned to command the 14th Regiment. The men learned that among the dead at Chancellorsville was Colonel James M. Parrin, who had taken that first company out of Abbeville.

From Chancellorsville, the Brigade was once more on the move with the line of march carrying them northward. On June 25th, the Brigade forded the Potomac River and marched onto the soil of Maryland. The troops were in high spirits. The McCurry’s were highly pleased with the change from Virginia. The Maryland citizens were not overly friendly but very gracious in giving them food, which the men had saw in abundance. It could be bought cheaply with greenbacks and even with Confederate money at prices sometimes less than in Virginia. They were surprised to see some Confederate flags displayed.

On June 27th, they stood on Pennsylvania soil. They felt this was their first real invasion of the North. They were amazed to find themselves in such a beautiful country. In every direction extended ripening fields of grain. On every farm there were herds of fat cattle. The barnyards were filled with poultry, and flocks of sheep grazed in numerous pastures. The orchards gave promise of a bounteous harvest. The citizens bade the Confederates to help themselves to whatever they cared to eat but to spare their more valuable property. Civilians frequently gathered at the wells where the Confederates stopped to drink. The conversations were always friendly.

The fourth night in Pennsylvania, the Brigade bivouacked near Cashtown. It was here they received marching orders at daylight on that morning of July 1st. As the McCurry’s heard the command to “move out,” they were heating some coffee, a rare, cherished treat, over a little pile of burning sticks. They had to drink it scalding hot, while washing down a few bites of cold food. Knapsacks were piled up to be left under guard and the units formed for the march. Artillery units were passing along the road in haste, and the McCurry’s read all the signs of an impending major battle. Soon to the shouting of officers and non-coms, they were out onto the now infantry filled road. The line of march was carrying them into the sun. The vibrations of artillery opening in the distance were already audible.

About 11:00 a.m., the Brigade turned off the road to the right and formed for battle facing toward that little town of Gettysburg, which they could now glimpse among the trees some distance ahead. The artillery, earlier heard in the distance, was now at hand. The guns were firing with unabated fury, reverberating over the rolling terrain. And from amid the folds of that irregular terrain ahead came the sound of musketry, firing with a vengeance, mingled with the defiant yells of attacking troops. And up from those folds, smoke ascended into view to drift with the whim of the thermal currents over the heat of the battle. The Brigade now advanced about one-half mile, passed through a wheat field, and rested. Federal prisoners and the walking wounded were now passing through the Brigade’s lines in a steady stream and moving to the rear. From these came varying accounts as to the progress of the battle. Again the order came to advance. The Brigade moved through a meadow, crossed a small stream, ascended a slope, and moved over the rounded crest of a smooth hill. Here, they came onto a brigade, of North Carolinians and Mississippians. These troops had been heavily engaged, and everywhere the ground was littered with dead and wounded bodies.

Now the McCurry’s saw that the lot cast for them was once again into the fray. Colonel Perrin had given orders that once the brigades lines were in motion against the Federals, there was to be no stopping. Also, there was to be absolutely no firing until the order was given. As the Brigade began its advance, it came into direct view of the Federal artillery which was positioned on the ridge ahead (Seminary Ridge). The guns opened on them with full fury. Shells dropped men from the lines, but the ranks closed in to fill the gaps and the Brigade pressed on. When about 300 yards separated them from the Federal lines, the enemy artillery switched to canister, and the enemy Calvary, with their newly issued repeating rifles, poured their missiles of death into the Brigade’s ranks. Men were dropping fast and the lines began to falter.

At this point, Colonel Perrin appeared, spurring his horse up through the ranks. Shouting and waving his sword, he went forward. The men could now plainly see those blue uniforms of the Yankee infantry with the muzzles of their rifles spouting flames. Opening fire, they continued the advance. Soon they were at close quarters, loading and firing with all deliberate speed into those blue uniforms. Presently those blue lines have begun to falter. Then suddenly they were disintegrating, and the backs of those blue uniforms were seen as the men were running in disorder towards the outskirts of that little town.

The Brigade’s 1st Regiment and the McCurry’s 14th Regiment were ordered forward on the heels of the fleeing Federals. These two regiments became the first Confederate troops to enter Gettysburg and raise the Confederate flag. Colonel Joseph N. Brown, commanding the 14th, later described the moments in his writings: “General Robert E. Lee, then rode up and all honor was given to the South Carolina Brigade (McGowan’s) that captured Gettysburg.”

The cost had been heavy. The 14th Regiment had carried 475 men into action. Of that number, more than 200 were killed or wounded. Losses in the Brigade’s other two regiments were equally severe. This, despite the fact that the assault lasted only some 15 to 20 minutes. The carnage that was the Battle of Gettysburg was to continue July 2nd and July 3rd and end in tragic defeat for the Confederate forces.

On July 5th, Lee's army took up the cheerless march along sodden roads leading southward. John S. McCurry, however, was not among the ranks. His Confederate War record states, “Wounded at Gettysburg and left with the enemy.” Colonel brown states that 90 members of the 14th Regiment were too gravely wounded to be removed south of the Potomac. John S. McCurry was among this group. Speaking of the wounded, in the aftermath of the assault, Colonel Brown stated, “Dr. Lewis V. Huot, the eminent Sergeant of the 14th, performed many skillful operations…” John S. McCurry is sure to have suffered the dreaded fate of his leg being amputated without any painkiller, amid the nightmarish screams he recalled from earlier battlefields and of his severed legs being thrown onto a pile of human parts outside the window of some crude structure serving as an aid station.

One can hardly comprehend the mental anguish of John S. McCurry, left in the hands of the enemy, hundreds of miles from Diamond Hill and tortured by searing pain in the stump where his right leg had been.

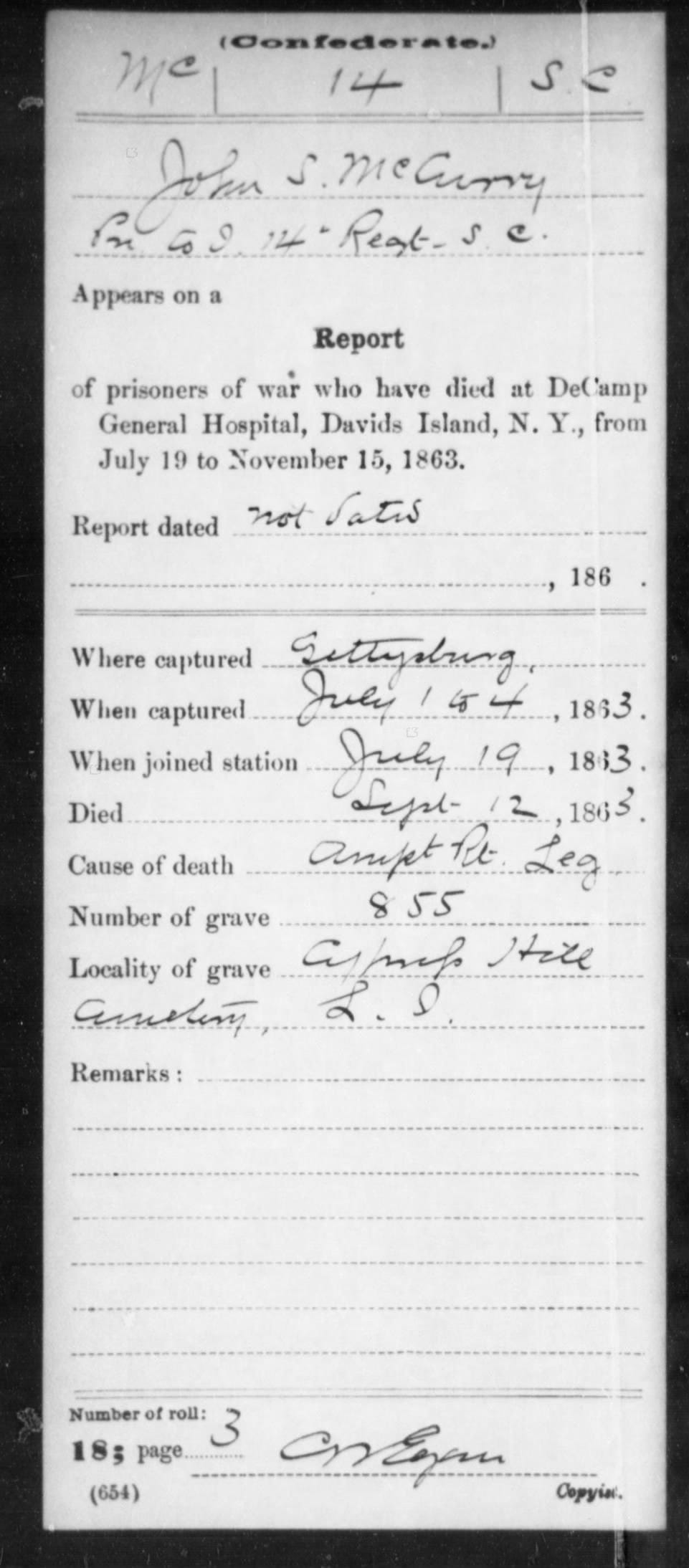

Records obtained from the National Archives state: “John S. McCurry, Private Company I, 14th South Carolina Regiment, appears on a report of prisoners of war who died at Decamps General Hospital, Davids Island, (Westchester) New York, from July 19th to November 15, 1863. Cause of death—apt. rt. leg.” The specific date of his death shows September 12th, 1863, two years and nine days after he was mustered into the Confederate service.

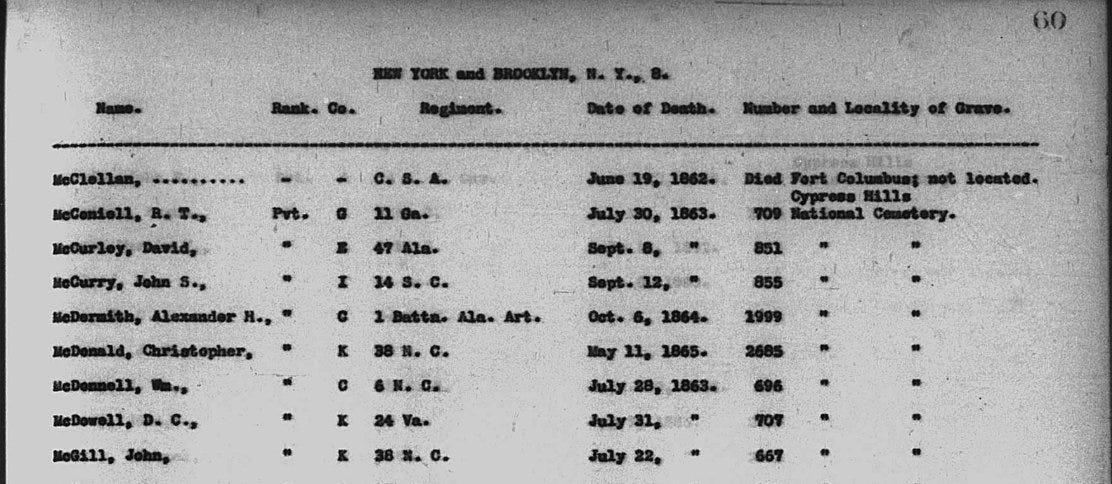

The experiences of the McCurry cousins reflect the harsh realities of the war as lived by tens of thousands of those other common soldiers who served in the Confederate Army. Today, more than one and a half centuries removed from that tragic era, “Rebels” and “Yankees,” their respective indoctrination dissipated in death, sleep the eternal sleep in Cypress hills National Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York. 488 members of the once great armies of the Confederacy are buried here. And here rests the remains of John S. McCurry. The marker on his grave (number 855) simply states, “John S. McCurry, S.C., C.S.A. (Confederate states army). The marker to the right reads, “John A. Swart, N.Y., U.S.A.” The marker to the left reads, “Simon Long, Louisiana, C.S.A.”

The Cypress hills National Cemetery was established to provide a burial place for those soldiers who died in military hospitals in the New York area, many of whom were from the bloody fields of Gettysburg.

Vivid descriptions, ample history made more personal by virtue of talking about "regulars" and "volunteers". Their struggles are riveting, humbling me. I really value your work.

I'm glad you are doing better and are back, I missed you, Monica! When I read your articles, I can visualize as I read, you put your all in your writings, I greatly appreciate you. Thank you for another piece of history.